Заигрывать: to flirt

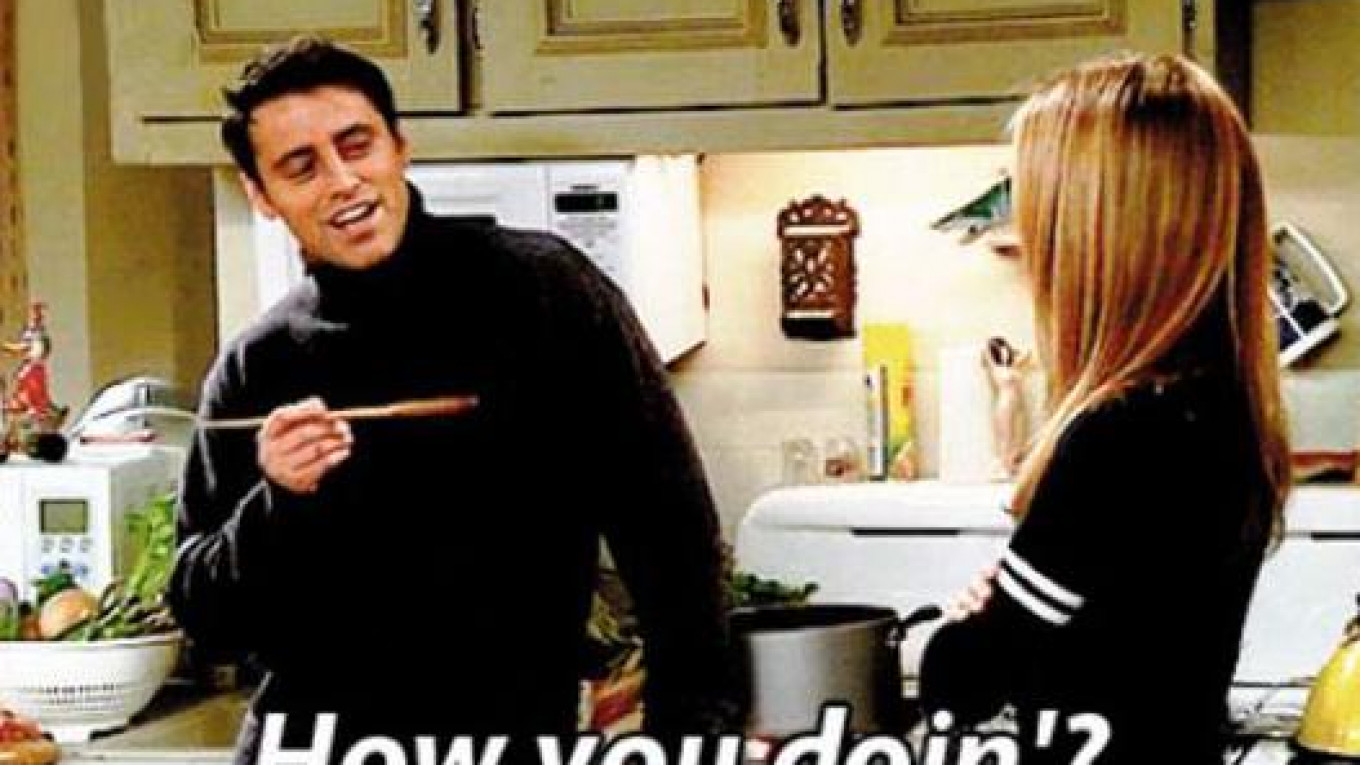

I walked into a small shop the other day to see a handsome young man smiling at the saleswoman over the cash register. The young woman handed him his change and said: “Только не надо борзеть!” He looked pleased with himself, she smiled in spite of herself, and I understood everything — except what she said.

So I came home and looked it up. Now борзеть is my new favorite verb. It means “to be insolent,” so the cashier was saying, “Don’t get fresh with me!” But the level of impudence in борзеть seems to range from charmingly cheeky, like the guy chatting up the cashier, to truly inappropriate: Андрей быстренько стал борзеть, жену тиранил, гадости ей говорил (Andrei quickly began to act up — he terrorized his wife and said horrible things to her.) Sometimes борзеть is beyond bad: Совсем страх потеряли, борзеют (They’re not afraid of anything or anyone. They’re completely out of line.)

Борзеть has produced the verb доборзеться, which like all verbs of this type (intransitive — that is, ending in -ся — with the prefix до-) means to act so badly that your insolence lands you in trouble. I’d like this verb more if it didn’t seem to be used almost exclusively to describe wives who weren’t submissive enough: Жене надо задуматься о том, что можно доборзеться и до развода, если не уважает мужа (A wife should think about the fact that she might smart-aleck her way to a divorce for not respecting her husband.) But you could also say to a man or woman: Доборзеешься, пощёчину получишь (You keep talking fresh like that and you’ll get slapped.)

On the sunny side of борзеть are verbs that let you chat up someone within the bounds of propriety. You might кокетничать (to flirt), although some people think there is an age limit on this: Он не кокетничал, ему было за сорок (He didn’t flirt; he was over 40.) It seems флиртовать (to flirt) is used slightly more often to describe women and their behavior, but this is not a hard and fast rule: Он сидит за столом, радуется хорошему вину, шутит, флиртует с дамами (He sits at a table, enjoying the good wine, making jokes and flirting with the ladies.) And you’d be surprised at who you can flirt with: У русских интеллектуалов склонность флиртовать с правительством (Russian intellectuals have a tendency to flirt with the government.)

Another word is used even more often for political or ideological flirtation — заигрывать (to flirt, come on to). In most cases there is a tinge of disapproval, either about the object of flirtation or about the way it’s done. For example: Нельзя заигрывать с политическими экстремистами (You shouldn’t flirt with political extremists.) В 1989 году Политбюро и Горбачев, которые уже заигрывали с западной демократией, решили провести выборы по-другому (In 1989 the Politburo and Gorbachev, who were already flirting with democracy, decided to hold the elections in a different way.) It sounds as if the leaders of the Soviet Union decided to change the system on a lark.

Of course, заигрывать is not just Communist Party behavior, it’s get-down-and-party behavior. On the flirt-o-meter it registers as quite active — more than a wink and a nod: Саша сыплет комплиментами и заигрывает со всеми девушками, и уговаривает одну удалиться с ним в лесок (Sasha piles on the compliments and makes passes at all the girls, and then talks one of them into going off into the woods with him.)

Finally, there’s заискивать (to curry favor with), which is fake flirting with an ulterior motive. This is what some folks do with their bosses: Начальника побаиваются и перед ним заискивают (They’re afraid of the boss and suck up to him.) This fawning is often done with the dreadful заискивающая улыбка (ingratiating smile).

Thinking back on the scene in the shop, it’s hard to say if the guy was flirting or fawning. I guess is depends on what kind of favors he wanted — kisses or apples.

Michele A. Berdy is a Moscow-based translator and interpreter, author of “The Russian Word’s Worth,” a collection of her columns. Follow her on Twitter @MicheleBerdy.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.