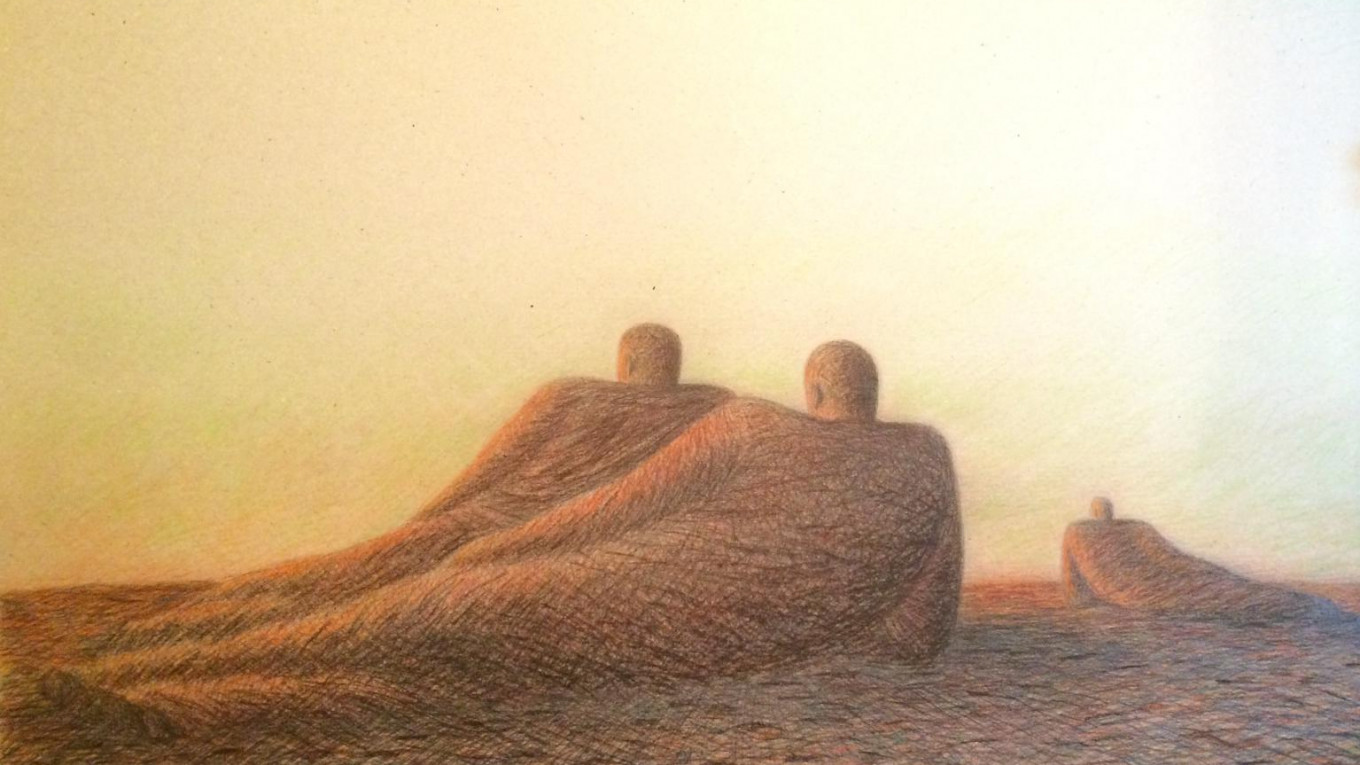

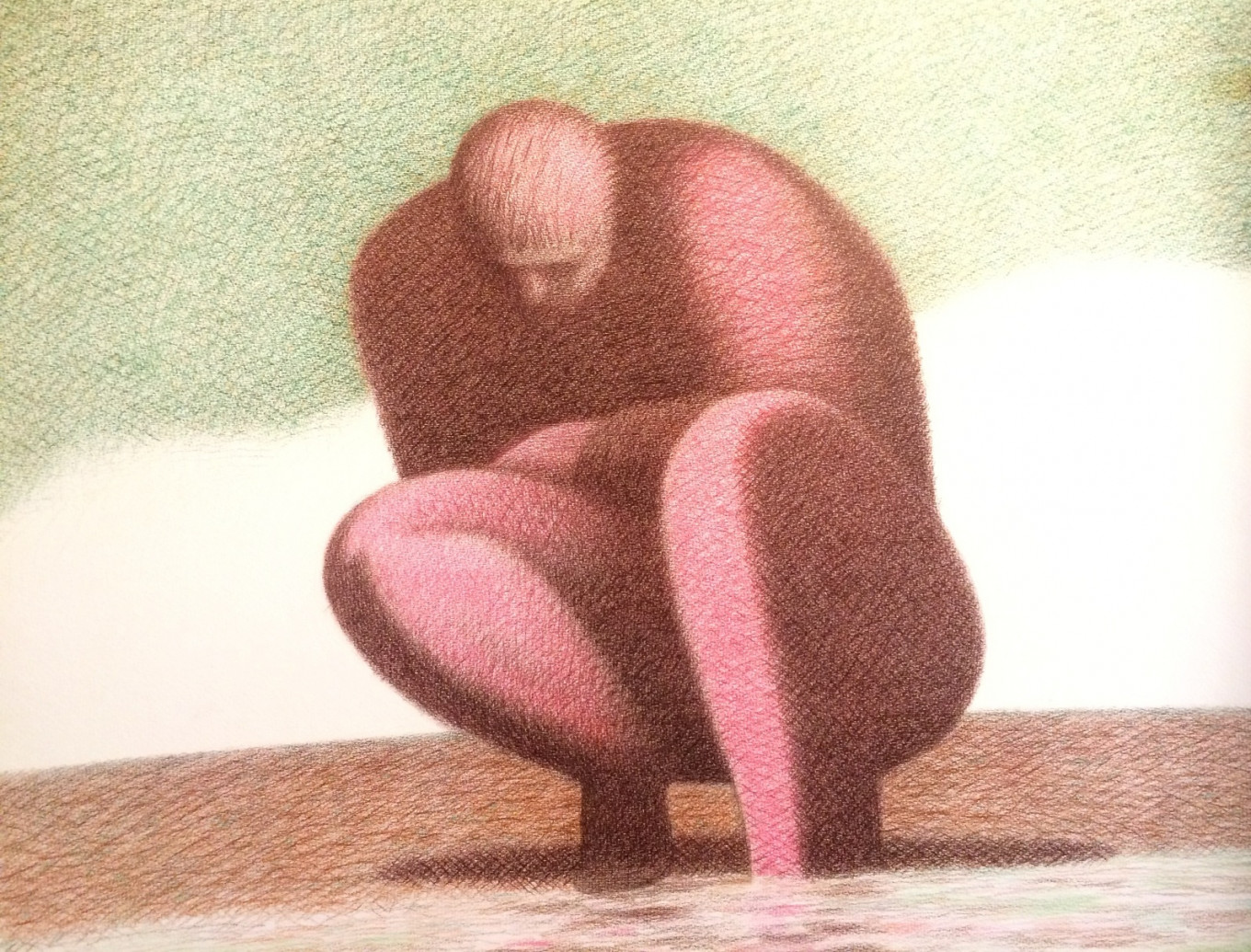

A highway with a lone lamppost stretches off into an infinity of desert dunes. Two guards in fur hats and overcoats stand smoking in the midst of a vast, boundless steppe. A man squats before a pool, peering into the water, nothing but sky and a distant flat horizon behind him.

For Garif Basyrov, empty space was a source of meaning, an artistic idiom that he used to transform his simple graphic depictions of everyday Soviet activity into a deeper and more universal reflection on the human condition.

For the first time since his death in 2004, this Tatar artist’s work is being shown at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. The museum has devoted two rooms to Basyrov’s surreal, sparse explorations of life in the late Soviet period, alongside a series of etchings and a body of sculptures produced in the 1990s.

Basyrov’s early years possibly hold a clue to the themes the artist developed as a grown man: He was born in a colony for “wives of traitors to the Motherland” in what is today northern Kazakhstan.

Given these circumstances, perhaps it is no surprise that so many of his drawings are dominated by empty space and flat horizons. Indeed, those familiar with Kazakhstan will find a clear echo of the steppes and huge skies of Central Asia in the vacant backgrounds, boundless horizons and huge skies of many of his graphic works.

A master of technique

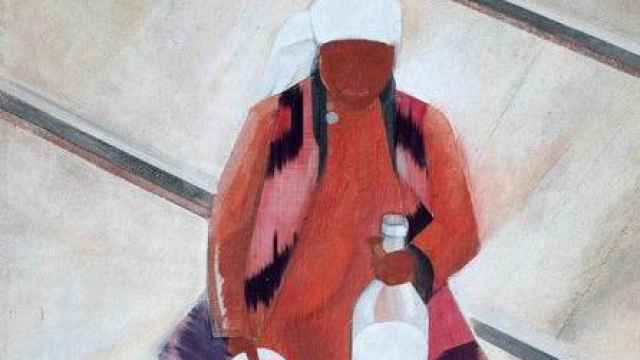

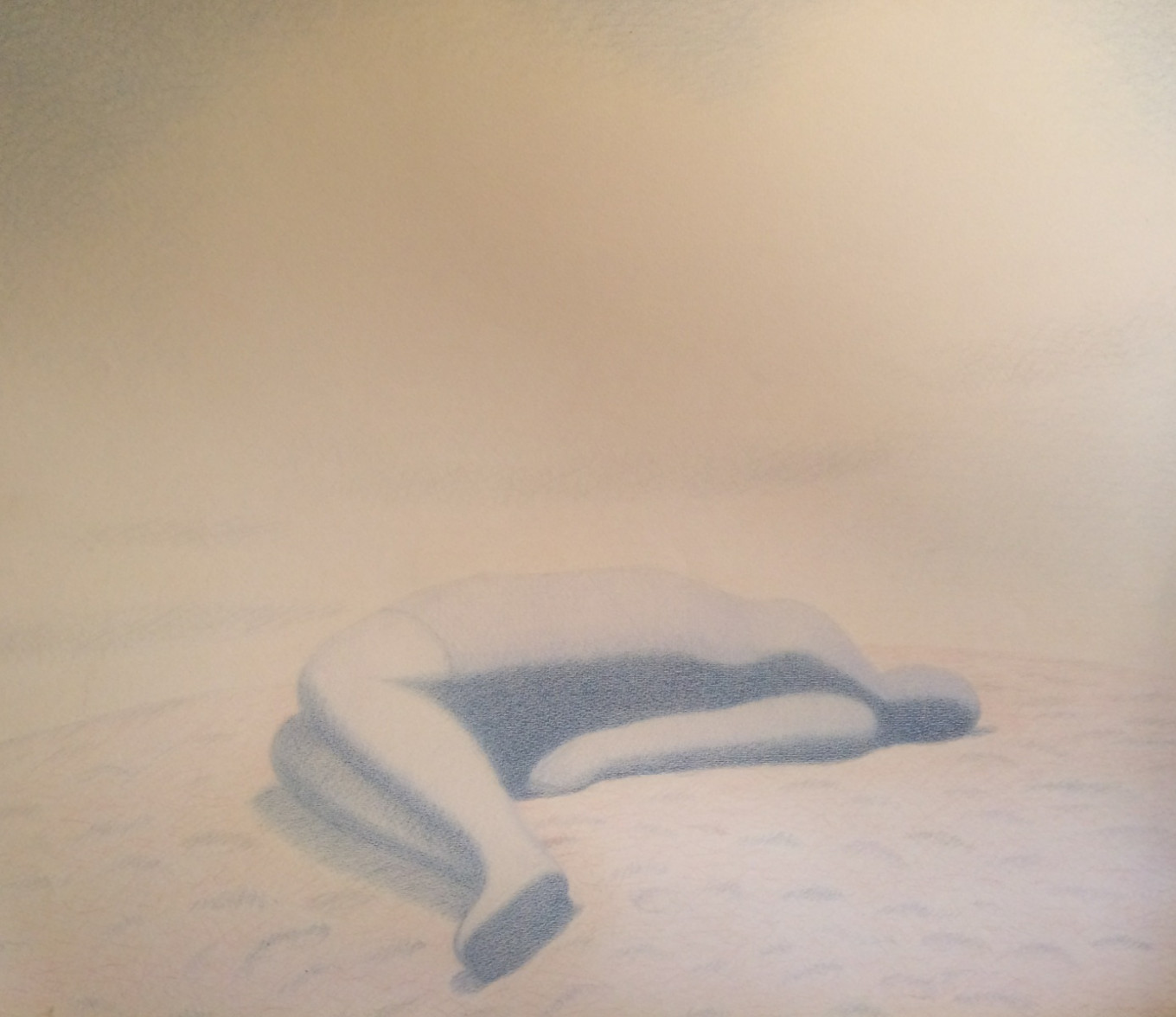

Titled “Inhabited Landscapes,” the exhibition is dominated by works from the series of the same name, a large body of drawings mostly executed in colored pencil and pastel on cardboard during the 1980s and early 1990s. The subjects may be simple, but Basyrov demonstrates a virtuosity of technique that places him clearly among the most technically accomplished of Soviet artists.

Up close, these graphic works turn out to be based on a form of hybrid pointillism. Using complex cross-hatching and sharp strokes of variegated color, Basyrov builds up an effect of prickly motion that creates the effect of soft, even textures from afar.

“He makes it look so easy,” says curator Alexei Savinov. “True professionalism is when you don’t see the artist’s labor. You see the image created, but not the work the artist has put into it.”

Soviet animator Yuriy Norstein (creator of the much-loved short film “Hedgehog in the Fog”) said that Basyrov’s lines and strokes were so well laid that you could make a fabric from it.

Yet there is little sense in trying to pigeonhole Basyrov via his style or genre — he neither fits the term “graphic artist” (he also made sculptures) nor is his work easily classified — is it abstract? Surrealist? Absurdist?

Essays on isolation

Many of the works in “Inhabited Landscapes” appear to be bleak, reductionist pictures of Soviet life in the 1980s. Here the gaping spaces and lack of detail and color often appear as a reflection of the monolithic, drab reality of late Soviet society: A cross-country skier puts his head down as he moves grimly forward along an infinite alley of blind walls; men roll giant snowballs in a driving blizzard, a game that seems more Sisyphean than winter fun.

Meanwhile, in “Subbotnik” a giant pile of felled trees rises against a background of blank white apartment blocks in what could be read as a metaphor for the striving of the Soviet state to shape the world to its will.

“Garif had an inherent, sharp feeling for history. His characters are both timeless yet at the same time firmly attached to our reality,” says Savinov.

At times there are hints of something darker: Are the indistinct figures lurking in a birch wood in “April II” just out for a weekend stroll or is there something more sinister at hand? Is one of them knocking another to the ground among the trees, or is this a depiction of some altogether more innocent activity?

Other pictures verge on surrealism: A suited man lies on his side, slowly submerging in rising water; a sleeping figure hovers in a pale night sky above a city.

While the exhibition is dominated by “Inhabited Landscapes,” it also acquaints the viewer with 40 pieces from Basyrov’s “Incubi” cycle, a series of small sculptures produced in the mid-1990s. These take the form of discarded fragments of wood, some left unworked, others carved into torsos or robed figures. They are adorned with a range of miniature household junk: handles, hinges, bolts, electrical parts, even a ring pull.

Unlike the sexually predatory male demons of myth, Basyrov’s incubi are more reminiscent of idols, the avatars of a multifarious, atomized new society built on the offcuts of a vanished civilization.

Indeed, says Savinov, most of the social archetypes presented in Basyrov’s work disappeared with the USSR.

“What resulted was the illustration of a vanished country. They remain universal as characters, but their ‘entourage’ has changed a little,” he says.

A universal idiom

Now, liberated from its original social context and geography, his art stands outside space and time: It has acquired a rare universality. These scenes have become archetypal situations of human experience: isolation, introspection, peace, complacency, the striving for liberty — conditions with which we can all identify. The beauty of Basyrov’s art is that it is as capable of speaking equally to a tribesman with no knowledge of the modern world as it is to an inhabitant of the city.

And while the voids that permeate Basyrov’s work may speak to many of loneliness, in a way this space creates room for interpretation, for thought, and at times, for hope.

In his picture “Sky and Stars,” a group of men wearing suits and ties stand rooted to the ground, heads craned skyward. Above is a vast gulf of empty space, but sprinkled across the very top of the picture is a narrow band of stars. And as that well-known aphorism by Oscar Wilde goes, we may all be in the gutter, but some of us are staring at the stars.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.