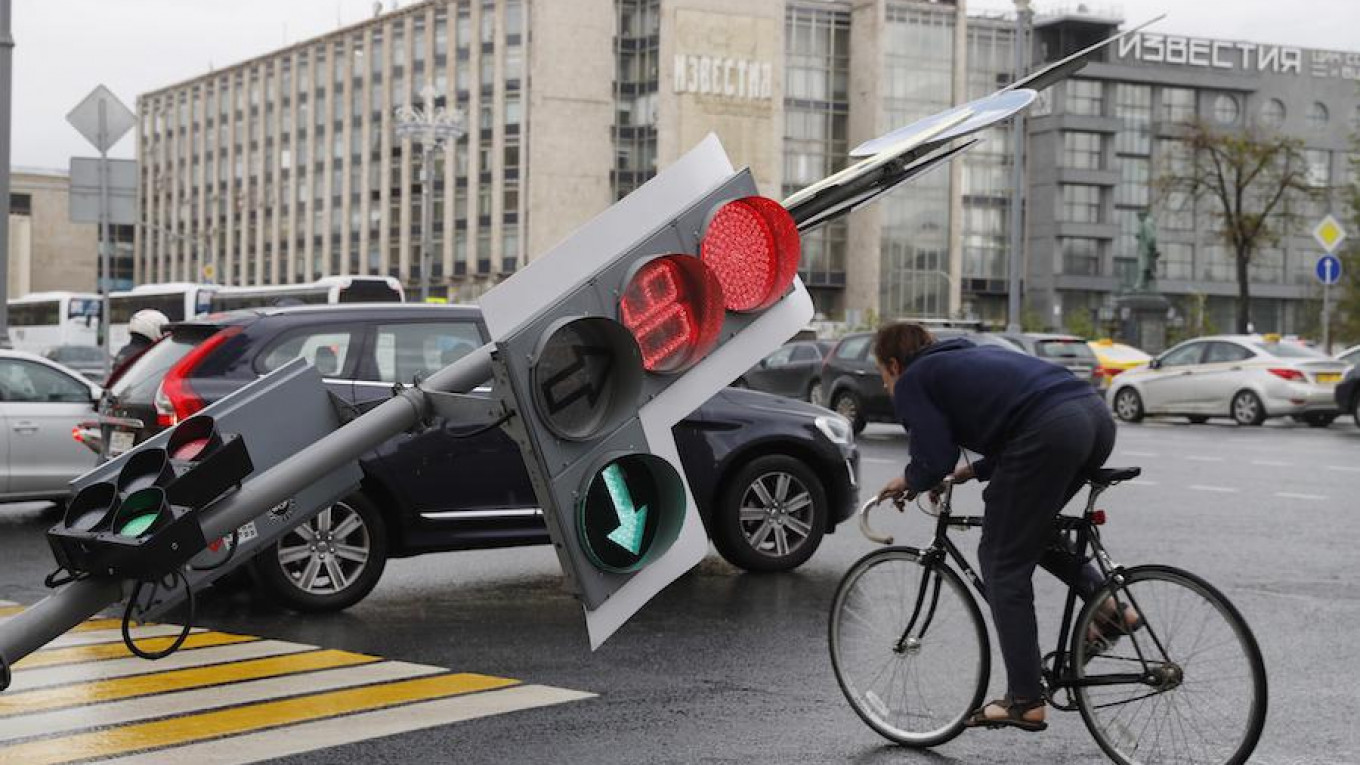

It seemed to come out of nowhere: Rain, hail and heavy winds of up to 27 meters a second tore down fences, tin roofs and signs. Moscow’s “hurricane” uprooted trees and spewed broken branches onto the streets.

The winds toppled a bus stop near the Prazhkskaya metro station and destroyed an iconic pyramid structure on the Novorizhskoye Highway. In the town of Lyubertsy, on Moscow’s outskirts, the gusts even knocked down a construction crane.

When the May 29 storm ended, 16 people had lost their lives. Branches and trash littered the streets. Apocalyptic images and videos circulated through social media.

The violent winds caught Muscovites off guard. The city’s denizens have grown accustomed to receiving extreme weather alerts by text message from the Emergency Situations Ministry. But, this time, many received nothing.

Now they are wondering: What happened? And why wasn’t the public warned?

Who’s to blame?

Both ordinary Muscovites and the media have taken to labeling the sudden storm a “hurricane,” a term frequently applied to extreme weather in Russia. But that isn’t entirely accurate, says Roman Vilfand, director of the Russia’s Gidromettsentr meteorological center.

Technically, the storm is a squall line, a string of thunderstorms that form in front of a cold front, producing heavy rain and strong winds. In practice, however, that distinction is likely lost on most people—and not without reason.

On the day following the tragic storm, 108 people remained hospitalized with injuries sustained from falling and flying debris. The wind knocked over more than 14 thousand trees and damaged nearly 250 roofs and 2000 cars, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin wrote on Twitter.

As of May 30, thirty thousand people were working to clean up after the storm, repair damaged infrastructure and provide electricity to suburban Moscow, where more than seven thousand people were left without power.

Meanwhile, the Emergency Situations Ministry (MChS) and mobile phone operators are trying to hash out who’s at fault for the absence of a storm alert. In winter, Muscovites receive frequent text message warnings about declining weather conditions—wet snow, slippery sidewalks, black ice, dangerous roads. Warnings are fewer in the spring and summer, but they still come.

This time, however, only some Muscovites got an alert,

and that message only warned of impending rain and storms.

Others received the message after the “hurricane.”

The mobile companies blame Emergency Situations. The Ministry determines who receives warnings, and the mobile operators’ role is limited, spokespeople from the Megafon and MTS companies told the Meduza news site.

“MChS can inform mobile subscribers [about dangerous weather] without the involvement of the mobile operators,” the MTS representative said.

But Emergency Situations says the mobile operators are to blame. The Ministry told Meduza that it ordered a weather warning from three major mobile companies: MegaFon, MTS, and Beeline. MegaFon claimed that MChS’s order only covered part of Moscow.

Meteorologist Vilfand notes that his agency, Gidromettsentr, had published alerts about the impending weather. Based on this, Emergency Situations wrote it’s own “interpretation,” recommending Muscovites avoid standing under trees or parking cars there. It was, by his account, a good message.

“I saw the interpretation myself,” says Vilfand. “But it’s possible it didn’t reach anyone.”

That increasingly appears to be what happened. On the afternoon of May 30, the Vedomosti news site, citing sources in two mobile operators, reported that Emergency Situations had sent out its storm warnings too late—at around 4:30 p.m. when the storm had already caused significant damage.

Beyond poor timing, the need to alert every mobile subscriber at such short notice may have overloaded the operators’ servers, Vedomosti’s sources said.

Safe City

The storm raised concerns about the safety of city structures. Tin roofs and signs were hurled across streets, creating serious danger for Moscow residents.

Urban decay is a visible problem in many neighborhoods of Moscow and even buildings in reasonable upkeep can have structural weaknesses. But Vilfand doubts that this an important factor in understanding what happened during the storm. When winds reach a speed of 25 meters per second, roofs and trees simply go flying, he says.

“When you have catastrophic events like this, it’s hard to blame the architect,” he added.

Konstantin Mikhailov, coordinator of the Archnadzor architecture preservation organization, largely agrees with that assessment. But he believes there should be a “real” investigation into the collapse of the bus stop, which killed one person. He suggests the bus stop may be been built or mounted incorrectly. Other than that, however, most of the damage “isn’t unusual for this kind of weather,” he said.

Vilfand emphasizes that, since extreme weather is unavoidable, the best that can be done is to warn people. Around the globe, meteorological organizations like his have a high success rate: 92 to 94 percent of their dangerous weather forecasts prove accurate, he says.

Meteorologists try to provide storm warnings “as quickly and accurately as possible,” Vilfand says. “But it doesn’t always work out.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.