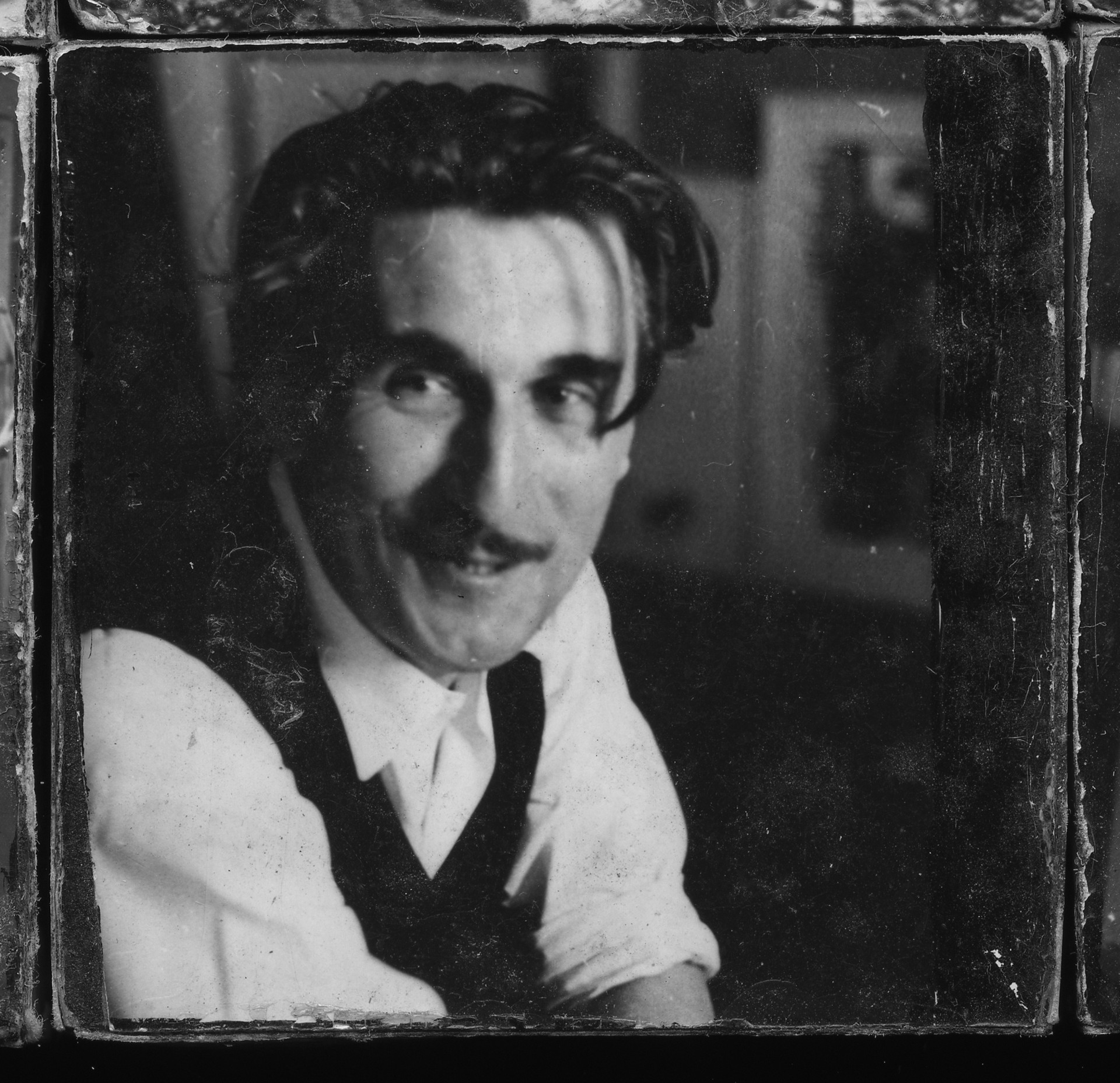

Before you go to the new exhibition called “The Game” at the Anatoly Zverev Museum, there are a few things you should know. First, this small museum is dedicated to the artist Anatoly Zverev (1931-1986), one of the finest non-official Soviet artists of the post-war period. But the museum doesn’t have a permanent exhibition on display, and this week the museum won’t look anything like it looked a month ago. Several times a year the curators develop the concept for a new show and change absolutely everything about the space of the museum, from the shape of walls to the lighting, adding specially made films, music, installations and other audio-visual material to create the appropriate context for the works on display.

Second, it’s probably best if you stop thinking of it as a museum in the traditional sense of the word—a place where you go to look at art. Think of it as a theater. You get a ticket, take off your coat, and become part of the audience for a show that will play out while you sit on benches or stroll about the space.

Third, leave your seriousness at the door. This show is meant to be fun. It celebrates Anatoly Zverev and his circle of artists, who, despite the extraordinary difficulties of their lives, had a great time with their art, and in the long, happy, alcohol-fueled games of cards that they played together. After all, the show is called Игра (“The Game”), which in Russian also means “play.”

In the words of curator Polina Lobachyovskaya, who spent countless days and evenings with the artists, the show is designed to “change the angle of your perception of them.” And part of that shift is to appreciate the play of art.

“Life for them was a game —cards, checkers, mythological drinking bouts… It was a tremendous amount of fun. And all their works of art were created in this atmosphere,” she said.

Friends united by art and cards

Works by Anatoly Zverev are displayed in this exhibition along with pieces by two of his contemporaries: Dmitry Krasnopevtsev (1925- 1995) and Vladimir Nemukhin (1925-2016). All three were part of a loose movement of nonconformist artists who were diverse stylistically and philosophically but united by their rejection of Socialist Realism, the officially prescribed style of Soviet art.

Anatoly Zverev, sometimes called the Soviet Union’s “first expressionist,” was a phenomenally prolific artist who, despite his extreme poverty (he often had no place to live) produced thousands of drawings and paintings—still lifes and portraits, most famously of women, but also of colleagues, friends and acquaintances. He loved to play cards, football and several Russian versions of checkers.

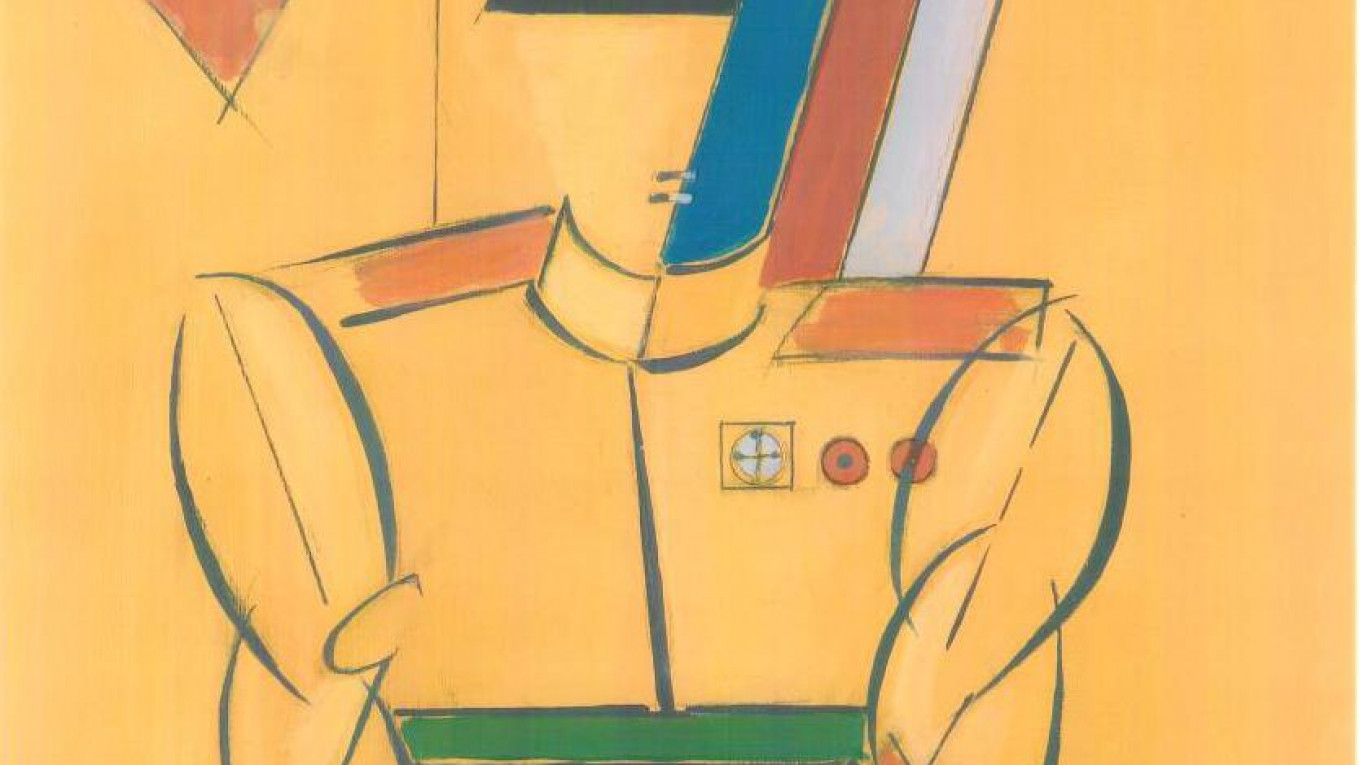

His friend Vladimir Nemukhin is best known for his exploration of card games on canvas. According to legend, Nemukhin once found a playing card on the floor of a tram and decided that it was a sign of his destiny. His canvases—expressionistic, incorporating collage, with nods to the early Russian avant-garde—are filled with numbered cards and images of jacks, kings, queens and jokers.

Dmitry Krasnopevtsev (1925-1995) was the least sociable of the group. He lived in a world of broken bits of ancient pottery, shells, scrolls and bones that he collected on expeditions far from Moscow. His “metaphysical still lifes” are symbolic and surrealistic, and it is sometimes hard to decide if they are whimsical or grim.

The fourth artist exhibited is part of the group not by personal history, but by “birthright.” Platon Infante-Arana is the son of another non-conformist artist, Francisco Infante-Arana (b. 1943), who created some of the first installations and kinetic arts in the late Soviet period. The younger Infante-Arana creates art pieces in which the physical dimension meets the virtual world. This playfulness, the curators say, takes the works of the original players to a new level in a new century.

The Game

In this artistic game, artists play with time— from the ancient world to the future—reality and virtuality, tradition and innovation, and each other. The show begins in the ancient world. On the first floor are nine paintings by Krasnopevtsev—odd bits of artifacts and otherworldly landscapes—line the walls of the room, while a multimedia work by Infante-Arana plays at one end of the hall. Called “The Iliad,” it consists of a bas-relief sculpted head fixed to what appears to be the wall. But as the words of Homer’s “Iliad” fill the air, virtual images on the wall seem to interact with the bas-relief head, playing with it, attacking it, destroying it and rebuilding it.

On the second floor the Game continues with Nemukhin’s canvases of cards, jacks and jokers that have come to life—or become still lifes—where the 20th-century avant-garde tradition plays with images and objects from the real world. Join the Game by sitting on a bench as card games are projected over you.

On the top floor, the Game is more complicated, and you might want to take a seat and follow the lighting cues. First you’ll see a short film with dozens of Zverev’s drawings, a chess board and other images. When the screen goes dark, turn to look at his illuminated still lifes, in which he plays with the symbols and images of the early avant-garde; and finally when they go dark, spin around to be mesmerized by Infante-Arana’s real life and virtual installations. And remember to have fun.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.