Vladimir Golitsyn felt safer in the evenings. The closer to midnight, the more unlikely the police were to arrive with an arrest warrant.

A member of one of Russia’s most famous aristocratic families, Golitsyn, an artist, lived for years in the Soviet Union as his friends from the noble class fled abroad, were executed or disappeared.

In a diary entry from April 1935, he describes the constant strain.

“There is a certain immunity in our family because since 1917 we have been pushed about, imprisoned, evicted or exiled,” he writes. “But such a lack of confidence in tomorrow cultivates a couldn’t-care-less attitude to your apartment, everyday life and so on. Is it worth changing the wallpaper? Is it worth fixing something if tomorrow they could kick you out?”

Arrested for the fourth and final time in 1941, Golitsyn died two years later in a Soviet labor camp. He was just 39, and left behind a wife and three children.

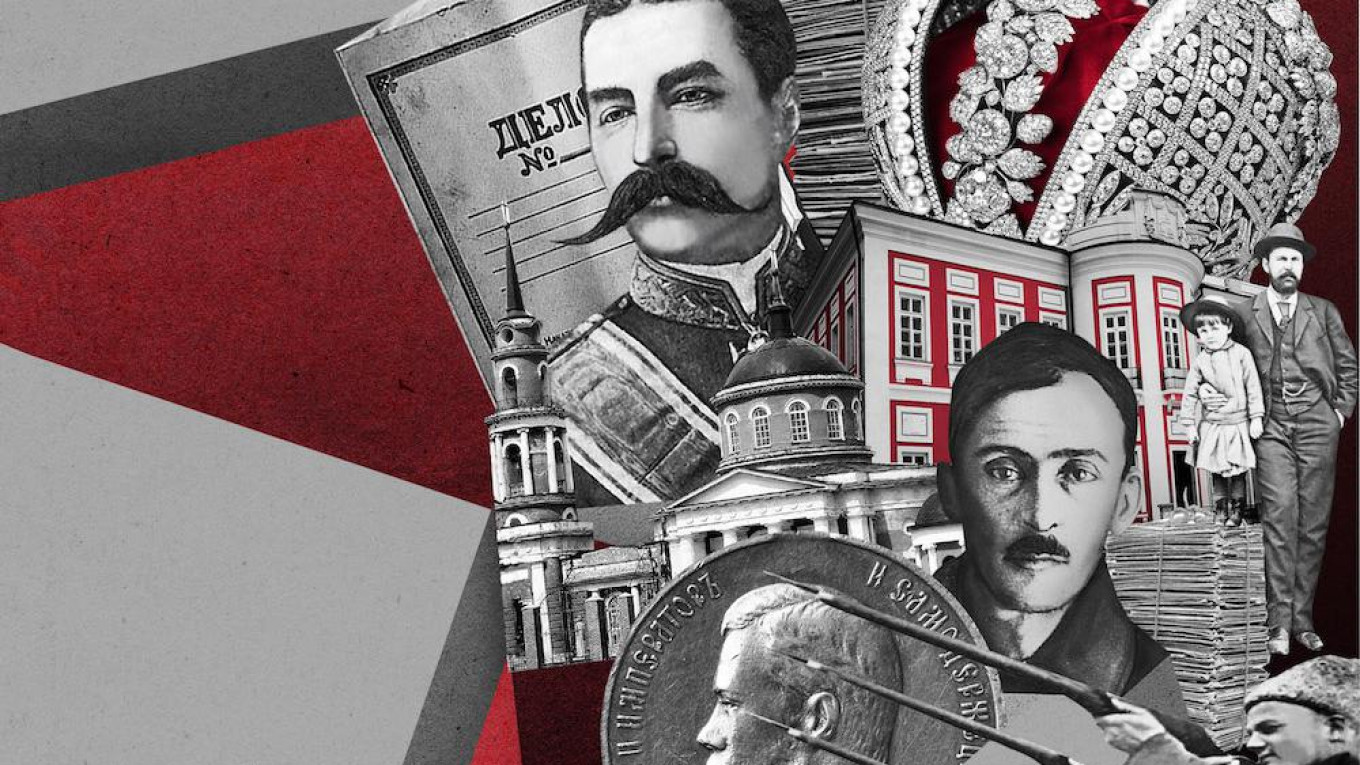

His story is one of many harrowing tales from the large aristocratic families that lost everything one hundred years ago as Nicholas II, Russia’s last tsar, abdicated amid a popular uprising, and Lenin’s Bolsheviks seized power.

In the new Communist country, the once wealthy and powerful elite became a hunted and persecuted minority. Most emigrated during the Civil War that followed the revolution.

“People with grand names, like Count Sheremetyev or Prince Golitsyn, who lived in grand homes and palaces, were clear and obvious targets,” says historian Douglas Smith, the author of Former People, a post-1917 history of Russian aristocrats.

“The fall that they experienced is something that we can’t even fathom in the West.”

The Golitsyn clan

For those who remained in Russia, it was risky to talk freely about their ancestry. The fear persisted even into the late Soviet period.

Aside from arrests and executions, former aristocrats could be refused documents needed for essential items including food. Some were evicted or denied jobs.

Banker Andrei Golitsyn, the grandson of Vladimir Golitsyn, says his parents were wary of open discussions. But they gave him and his siblings their memoirs to read, and never hid their origins or changed their names.

“We knew who we were,” he says.

He now lives with his wife and children in central Moscow, less than a kilometer from the still-standing Shuvalov estate his family once owned.

They occasionally play beautifully illustrated board games drawn and devised by his grandfather in the 1930s. Andrei Golitsyn also helps organize a family gathering on Jan. 13th— the anniversary of his grandfather’s birth.

The family have never forgotten Vladimir’s arrest. “Until his last days my father remembered how they came to take his father away,” recalls Andrei Golitsyn.

After graduating from university in the 1950s, Andrei’s father, Mikhail Golitsyn, lived in Kazakhstan for 25 years on the advice of a professor who said he would struggle to find work in Moscow. He became a geologist because the sciences were considered a less dangerous profession.

“Despite the loss of their wealth and property, of their privileged legal and social status, and of so many family members from imprisonment, exile, and death, the Golitsyns remained true aristocrats,” historian Smith says in Former People.

Keep it in the family

Andrei Golitsyn’s wife, Tatyana Golitsyn, is also descended from another branch of the Golitsyn family who were torn apart by the revolution.

Her relatives fled Russia and she was brought up in the United Kingdom. She met Andrei Golitsyn when she traveled to Russia in the 1990s as an English teacher.

“My husband’s a Golitsyn and my mother’s Golitsyn as well. But there are nine cousins between us of different generations,” she explains.

“All Russian people look at me like a complete foreigner which is a bit hurtful because I do have Russian roots. It’s not acknowledged,” she adds.

Tatyana Golitsyn’s grandmother, Irina Golitsyn, left the Soviet Union in 1932 after German President Paul Hindenburg—who was related to a Golitsyn—wrote to Stalin on her behalf.

Irina Golitsyn’s early life was defined by the revolution and its consequences. In her memoirs, she recalls the deep embarrassment she felt in 1917 when she could not tell soldiers searching her family’s large Petrograd house where to find the kitchen.

“I only knew where the lift was that brought food from the kitchens,” she writes.

Two years later, her father was executed. Irina was later arrested and deported to the central Russian city of Perm, where she met her future husband.

After settling in 1990s Moscow, Tatyana Golitsyn says she sought out traces of her grandmother’s family. She traveled to their ancestral estate of Stepanovskoe-Volosovo, located to the west of the Russian capital.

To her surprise, she found a 96-year old woman living in a nearby village who remembered Irina Golitsyn and her mother. The woman described how, under the tsars, peasants would line the road on their knees when her family arrived at the estate for a visit.

Living for the moment

The constant threat of arrest for aristocratic families in the early decades of the Soviet Union was demoralizing, but it also bred fatalism and meant they often lived for the moment, according to historian Smith.

The diaries of Vladimir Golitsyn from the 1930s are filled with—occasionally dark—humor.

In one entry in 1934 he recounts an incident with his brother-in-law, Nikolai Sheremetyev, a member of another old Russian family, who worked as a violinist at a Moscow theater.

“One summer during the interval the musicians ran into a beer shop opposite to freshen up,” Vladimir Golitsyn writes. “They had to wait ages for the beer. Nikolai began to complain. The waiter, who was bustling between drinkers, yelled at him: “What are you shouting for? You’re not Count Sheremetyev! You can wait!”

In an entry from July 1941 shortly after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, Vladimir Golitsyn makes light of losing his radio: “Yesterday they confiscated the radios. This is, of course, better than being shot for listening to foreign radio.”

For much of the 1930s, Vladimir Golitsyn and his family lived in the town of Dmitrov, north of Moscow, to comply with a Soviet order that their accommodation had to be at least 100 kilometers from the capital. Their house became a social hub for friends and relatives.

“Despite everything, they carried on living,” says Irina Chumak, head of the Golitsyn museum in Dmitrov, which opened in 2014 in the building the family rented.

Forgive but not forget

Nikolai Trubetskoy, the scion of another noble line, says hundreds of his family members perished in the Soviet Union. The first victim was his grandfather’s Daughter, who died from complications from a cold in 1917 Moscow, when street fighting meant a doctor could not get to the house. His grandfather, Vladimir Trubetskoy, was shot in 1937.

His father, Andrei Trubetskoy, spent six years in a labor camp in Kazakhstan.

Like his cousin by marriage Andrei Golitsyn, Nikolai Trubetskoy has invested time and money in the publication of his relatives’ writings. In 2015, he published his father’s memoirs, which features an altered Trubetskoy family crest on the cover with barbed wire, representing the camps, and birch trees, recalling his time fighting the Nazis as a partisan in World War Two.

Andrei Golitsyn has arranged for the publication of several of his predecessors’ memoirs, including his grandfather’s in 2015 and his father’s in 2008.

In a similar act of remembrance, a cousin of Tatyana Golitsyn, Katya Galitzine, who lives in the United Kingdom, founded a library in a former Golitsyn estate in St. Petersburg.

Nikolai Trubetskoy, whose nickname in school was “prince”, is also an amateur videographer and has recorded his relatives telling their life stories. He says that despite what happened to his family, neither he nor his father are motivated by hatred.

“My grandmother also suffered a lot under the Soviet Union and when we were young we asked whether she wanted revenge,” he says. “And she said something very correct: ‘I forgave these people a long time ago, though I have not forgotten.’"

Modern aristocrats

Unlike the relatively numerous Golitsyns, other prominent aristocratic families almost ceased to exist under Communist rule.

Nikolai Trubetskoy’s father, Andrei Trubetskoy, was the only male Trubetskoy to survive despite being one of ten children. And after the death of Pavel Sheremetyev during the Second World War there was not a single male Sheremetyev in the Soviet Union.

While relatives from abroad did much to continue traditions, many became distant and learned new languages. “They became different people and the people who stayed became different people,” says historian Smith.

Andrei Golitsyn says he agrees with his great-grandfather, a three-term mayor of Moscow under Russia’s last tsar, who believed the revolution happened because of decades of injustice. But Andrei prefers not to accuse individuals. “What happened, happened,” he says, “it’s difficult to blame people while sitting in a warm house in Moscow.”

Life and property rights in modern Russia are more secure than during the Soviet Union. Still, Nikolai Trubetskoy, now president of mid-sized logistics firm NEK Group, fears everything could be taken away again. “The authorities use the same methods: fear, fear, fear,” he says. “Everything could return to what it was like under Soviet power.”

Many see it as their duty to put their family on a more stable footing by producing heirs who will continue the name.

Nikolai Trubetskoy and his three brothers have 7 sons between them. Andrei and Tatyana Golitsyn have four sons. “We have to preserve the family and multiply,” says Nikolai Trubetskoy.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.