Until recently, Medical Clinic No. 32 was little different from thousands of other hospitals abandoned after the collapse of the USSR. It had the same gloomy institutional aesthetic, the same creaking parquet floors, dim corridors and decaying linoleum.

So when the disused building at Paveletskaya was offered to the Theater Union of Russia as the exhibition space for “Itogi Sezona,” its annual review of work by Moscow set designers, many of the artists were horrified. Instead of a clean, well-lit exhibition hall, they were faced with a disintegrating shell.

The floors were caked in dust, the windows dark and filthy, and the building also lacked electricity, having been stripped of its lights. To add insult to injury, the space was split into corridors and rooms, many of them odd shapes and sizes—a curator’s nightmare.

“Some of the participants, after seeing photos of the space, just turned up, left their work and took off [in outrage],” curator Inna Mirzoyan told The Moscow Times.

Since 1991 the exhibition has been held with varying degrees of success at venues around the city, including the Manezh and New Manezh exhibition halls and—more recently—the Zurab Tsereteli Art Gallery, but has never faced the task of having to convert such an unorthodox space into a gallery.

“Itogi Sezona” was traditionally held in the Actors’ House on Tverskaya Ulitsa, but after it was gutted by a fire in the early 1990s, cuts to the budget and dwindling funds meant relocating to progressively less prestigious venues. For this year’s show, the group turned to its long-time collaborator, the Bakhrushin State Central Theater Museum.

“We approached the museum and asked if we could hold the exhibition in the main building, but there was no space,” explains Mirzoyan.

Instead, the museum’s director offered the scenographers the use of the second floor of the neighboring Medical Clinic No. 32, which was given to the museum by the Ministry of Culture two years ago.

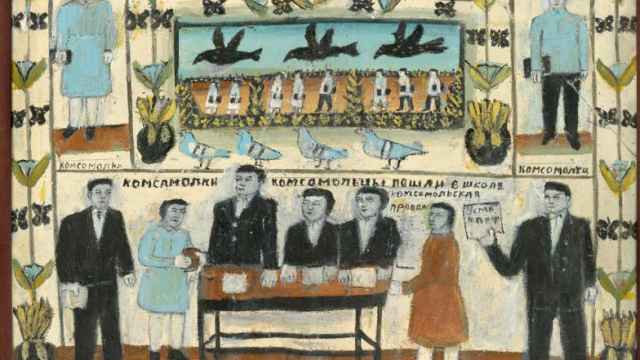

Since 1964, “Itogi Sezona” has served as an end-of-season review featuring models, sketches and costumes for projects Moscow’s scenographers have worked on over the year.

“The season ends, and everyone puts up their pictures. It’s like a Facebook feed, an archive of what has happened,” says Mirzoyan.

This year’s venue is a drastic departure for the exhibition, traditionally held in more conservative surroundings. The disused clinic presented the artists with a series of discrete, cramped spaces in which to display their work. And while some participants balked at the prospect, many rose to the challenge

“Of course it was an adventure, because in order to hold this exhibit, first of all we had to adapt the space,” explains Mirzoyan.

Polina Bakhtina, one of the participating artists, took on the role of exhibition designer and developed a unifying stylistic theme. Basing her approach on the concept of “moving out” and “moving in,” Bakhtina has decorated the space with cartons, white paint and duct tape—including the chairs in each room, which have been “packaged” in cardboard and yellow tape.

Bakhtina says this year's "Itogi Sezona" differs radically from all previous exhibitions by theatrical artists held in classical gallery spaces, describing the idea of displaying works by established scenographers and artists in former medical wards as "adventure," a kind of "hooliganism."

"Instead of the formal hanging of exhibits on walls, we've been able to create for the viewer a journey through completely different, unique scenographic worlds, from hall to room, from room to corridor, from light to dark. Everywhere there is a different light, style and mood," she says.

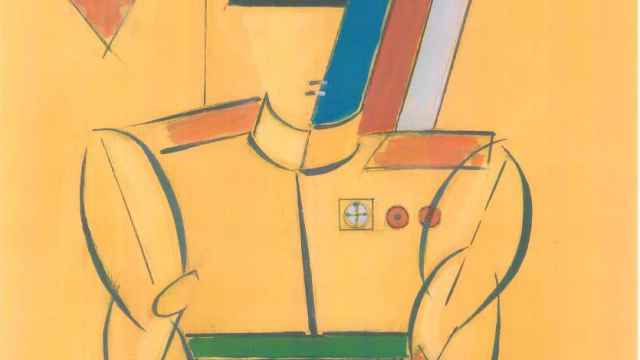

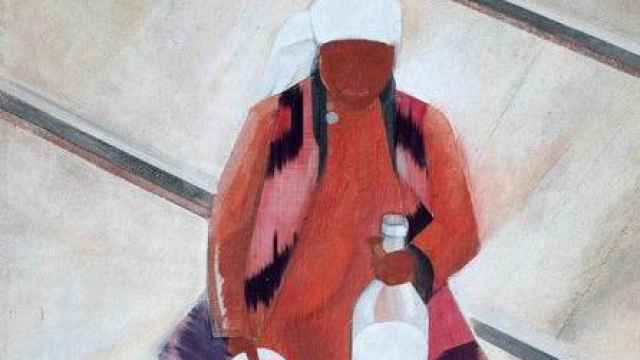

As the exhibition shows, a number of the participants have seized the opportunities offered by having the blank canvas of an entire room or passage at their disposal, transforming them at Bakhina's suggestion into total installations.

The chief stage designer for the Lenkom theater, Alexei Kondratyev, has transformed his room into an entire installation devoted to Vladimir Sorokin’s “Den Oprichnika” (Day of the Oprichnik). There are three set models, including the final one used for the play, as well as avant-garde works that formed part of the creative process for the project.

Bakhtina also highlights the work of Yury Kharikov, who completely transformed his room into a minimalist black-and-red pavilion based on the motifs of the play "Before Sunset," in which the viewer could draw on the walls with chalk.

For other set designers, the peculiarities of the space were an unexpected boon, allowing them to emphasize thematic elements of their productions and incorporate features of the abandoned clinic into their exhibit.

Natalie-Kate Pangilinan, who designed the set for a staging of Josef Brodsky's poem "Gorbunov and Gorchakov," inspired by his stints in two psychiatric hospitals, has made use of a white tiled wall to create her own ward, complete with white curtains and medical instruments. Sergei Tarakanov, meanwhile, has used an old medical cupboard to display a series of puppets.

It is this extra creative dimension, this artistic opportunism, that captivates, with the artists utilizing their natural talents to do what they do best: visualize space as a stage. In fact, there is something refreshingly innocent about this year’s “Itogi Sezona,” a sense of art returning to its roots, liberated from the buttoned-up confines of the gallery and taking back its role as something opportunist, irreverent, on the edge of the possible.

That the clinical environment of the modern-day exhibition hall has so much in common with the white-walled minimalism of the hospital is the most telling of ironies.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.