The Moscow Times and Project1917 bring you the next installment of the most compelling stories of 1917. In the seventh episode of our series, which takes place one hundred years ago this week, Lenin receives a less-than-warm welcome from his party, Alexandra Kollontai promotes socialism and feminism among soldiers' wives and mothers and British hospitality toward the Romanov family proves lacking. See previous episodes here.

April 17:

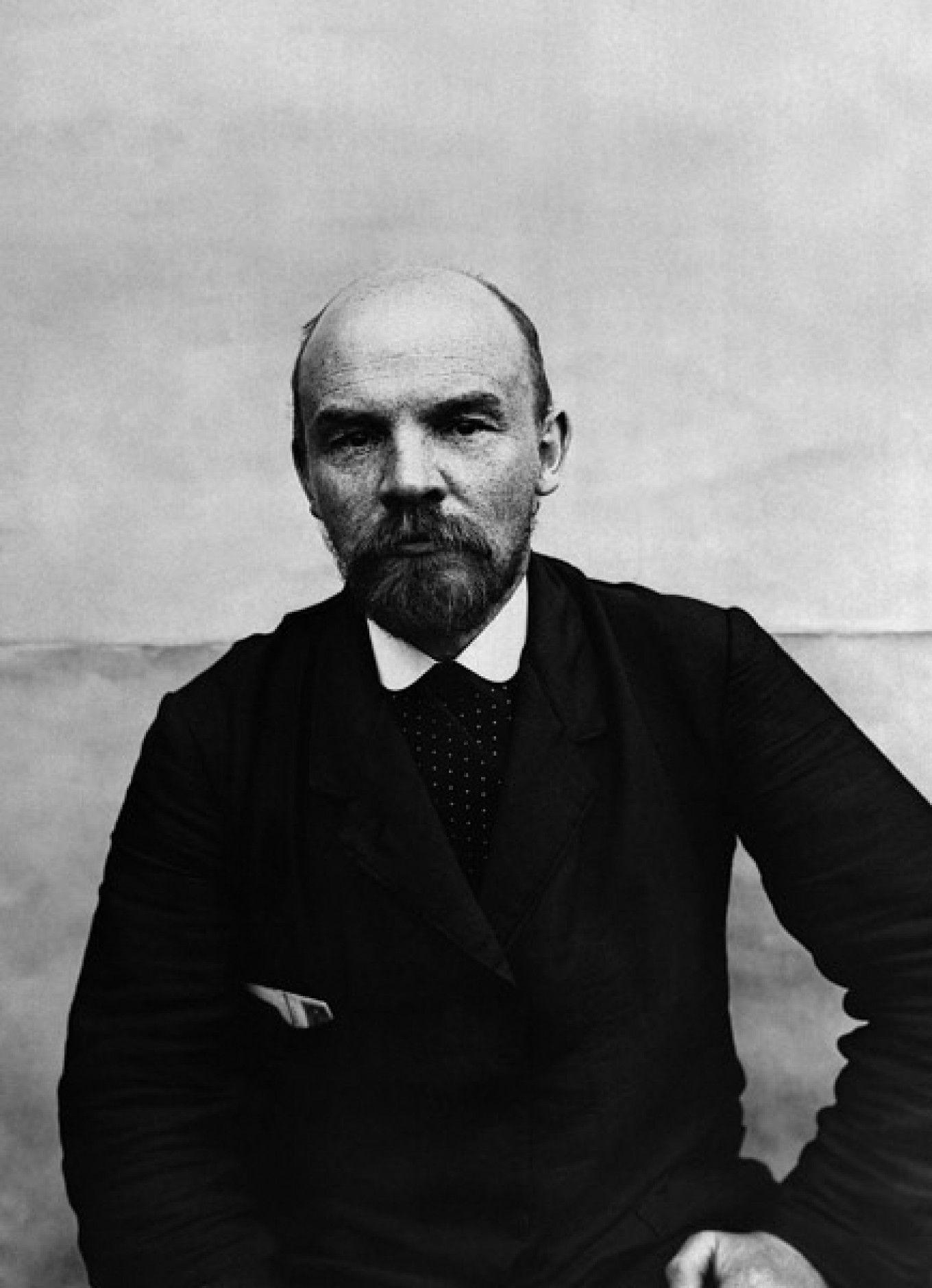

Shortly after arriving back in Petrograd, Lenin receives a less-than-warm welcome from his own party. His wife Nadezhda Krupskaya describes his failure at a meeting of Bolshevik deputies:

Ilyich [Lenin’s patronymic] had barely woken when his comrades came to take him to a meeting of the Bolshevik members of the All-Russian Conference of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. The conference was being held in the Tauride Palace, somewhere in the upper floors. Lenin has summarized his views on what needs to be done in ten theses. In these theses, he has assessed the current situation and given a clear and precise summary of what we should be aiming for and the paths we should take to achieve these aims. The other party members rapidly grew confused.

To many it seemed that Ilyich’s conclusions were too extreme, and that it was premature to speak of a socialist revolution.

April 20:

Alexandra Kollontai, Lenin’s close friend and one of the most famous feminists of the Russian revolution, is spreading pacifism and socialism among soldiers’ wives and mothers:

Lenin, Nadezhda Konstantinovna [Krupskaya] and I were walking together to the Tauride Palace and I told Lenin about my work with the soldiers’ wives and mothers. It’s wrong of us to see them as being in favour of the war, although it is true that the pro-war liberal women are making great efforts to organise them, create their own union of soldiers’ wives and mothers, and win their support. Meanwhile, we are doing nothing. I am the only one bothering with them. Now they themselves invite me to address them. They lament the current high prices. “Bring my husband back from the trenches,” they say. “What is this war to us?” There are many soldiers’ mothers, and even more soldiers’ wives with children, who are unable to survive on their rations. But how can they go to work when they can’t leave their babies? Lenin was interested.

April 22:

This is how Lenin himself describes the inner sense of the events of 1917:

The basic question of every revolution is that of state power. Unless this question is understood, there can be no intelligent participationб let alone leadership, in the revolution. The highly remarkable feature of our revolution is that it has brought about a dual power. This fact must be grasped first and foremost: Unless it is understood, we cannot advance. We must know how to supplement and amend old “formulas” — for example, those of Bolshevism. Because, while they have been found to be correct on the whole, their concrete realisation has turned out to be different. Nobody previously thought, or could have thought, of a dual power.

What is this dual power? Alongside the Provisional Government, the government of bourgeoisie, another government has arisen. So far, it is weak and incipient, but undoubtedly a government that actually exists and is growing — the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.

What is the class composition of this other government? It consists of the proletariat and the peasants (in soldiers’ uniforms). What is the political nature of this government? It is a revolutionary dictatorship, i.e., a power directly based on revolutionary seizure, on the direct initiative of the people from below, and not on a law enacted by centralised state power. It is an entirely different kind of power than the one that generally exists in the parliamentary bourgeois-democratic republics still prevailing in the advanced countries of Europe and America. This circumstance is often overlooked, often not given enough thought, but it is the crux of the matter. This is the same type of power as the Paris Commune of 1871.

April 23:

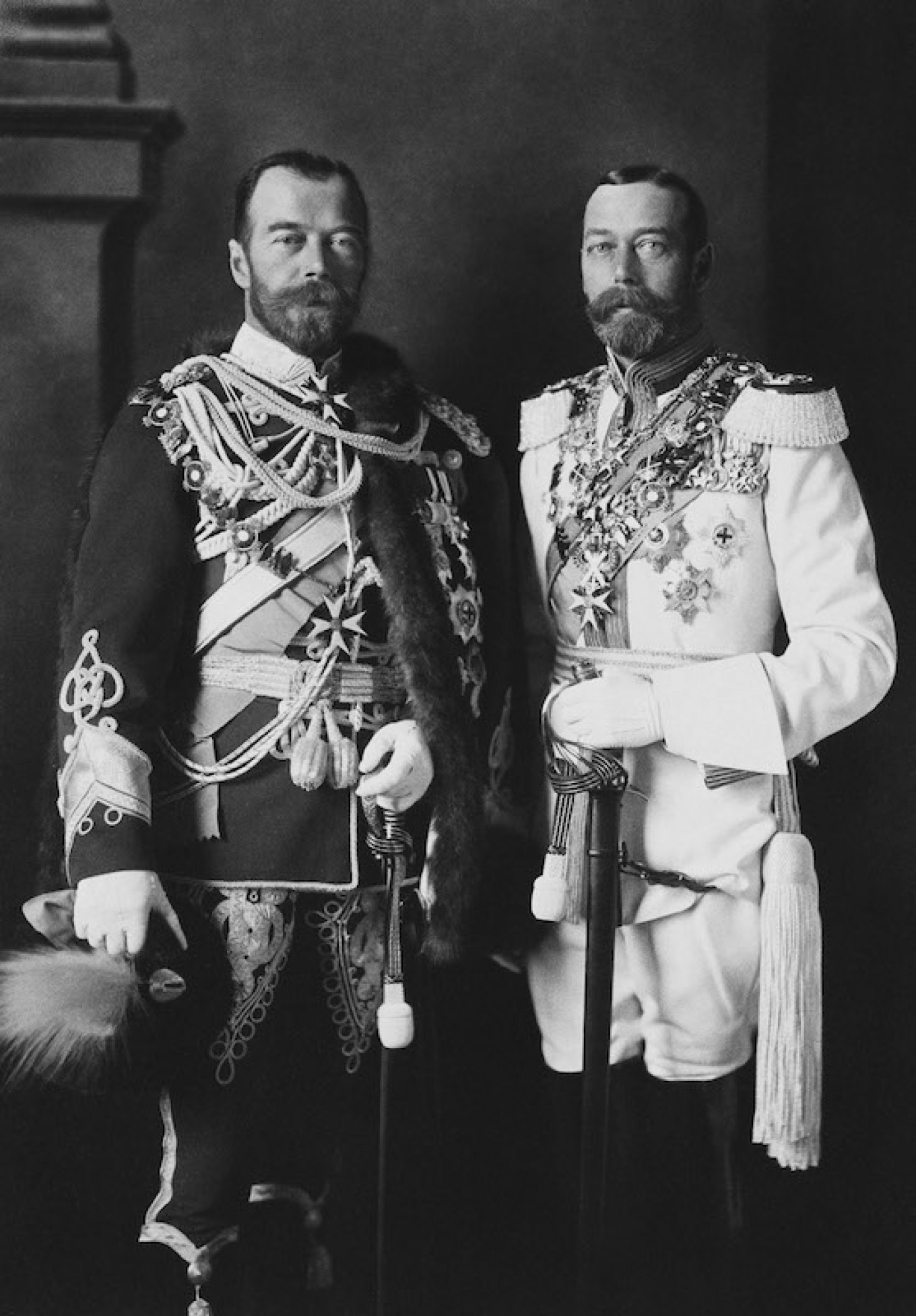

And the most important event of the week: The British government has changed its mind and rescinded its invitation for Nicholas II to come to England. The Tsar’s cousin, King George V, has failed to help to his friend and the whole Romanov family. Now they are left to meet their fate at the hands of the Provisional Government. Alexander Kerensky, a member of the Provisional Government, writes:

Meanwhile, the situation in London has changed. The British government has reconsidered its decision and declined to extend hospitality to the relatives of its own royal house for the duration of the war. Unfortunately, [British Ambassador] Sir George Buchanan did not immediately inform the Provisional Government of this decision, and it was still busy making preparations for Nicholas’s departure to England.

When the preparations were completed, [Provisional Government Finance Minister Mikhail] Tereshchenko asked Sir George to contact his government about when we could expect the arrival of a British cruiser in Murmansk to take the royal family onboard. And only at this critical moment did Sir George, with unconcealed sorrow, informed us that the arrival of the royal family in England is no longer considered desirable.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.