It’s fitting that the Tretyakov Gallery’s major retrospective dedicated to Zinaida Serebryakova coincides with the arrival of spring in Moscow. The 20th century Russian artist is known for her bright, joyful paintings and self-portraits.

The current exhibition focuses on the Russian period of Serebryakova’s career. It was a time the artist would later refer to as her “happy years.”

“What you sense from this collection of paintings is that she loved the life she had,” Tatyana Yermakova, the curator of the exhibition, tells The Moscow Times. “It’s tangible from the paintings she created.”

The current exhibition boasts the largest collection of Serebryakova’s works in over 30 years. It is a sequel to the gallery’s well-received 2014 retrospective, which was dedicated to Serebryakova’s life as an emigre in Paris following the 1917 Revolution. Organizers hope the current exhibition will acquaint a new generation with the artist, as well as delighting her many existing admirers.

The gallery began online ticket sales two weeks before the exhibition opened, capitalizing on the huge public interest in the show.

“She’s an artist that is very much loved by the Russian public,” says Yermakova. Serebryakova was born into an artistic family. Her uncle, Alexander Benois, was a founding member of the art movement Mir Iskusstva, to which Serebryakova loosely belonged.

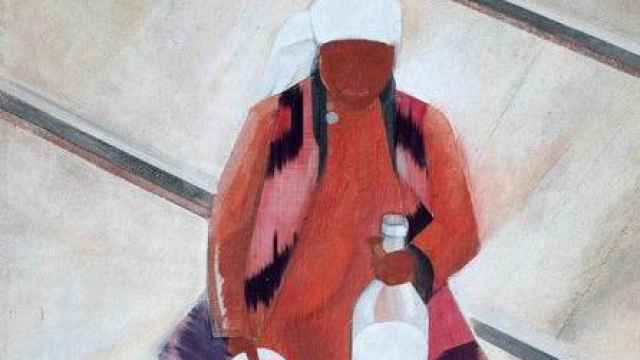

Yet Serebryakova didn’t have the structured artistic education of her contemporaries. She incorporated styles such as realism, impressionism and neoclassicism into her works, which often depicted her friends, family and everyday life.

“She was a very independent artist,” says

Yermakova. “A lot of the works from her

period in Russia were her own creations,

inspired by the beauty she saw in the world

around her.”

Serebryakova’s calling card, “At the Dressing

Table: Self Portrait” (1909), was the painting

that first brought her critical acclaim.

Exuding youthful exuberance, expressive

sensuality and a striking use of light, the

work was acquired by the Tretyakov Gallery

in 1910.

But while the Russian public may know Serebryakova best for her self-portraits, Yermakova is keen for visitors to become acquainted with the full range of her work.

“Serebryakova didn’t paint a large number of self-portraits because she was vain,” says Yermakova. “It was because she was the type of artist who only worked with what she knew.”

The exhibition boasts over 200 works, including an entire room is dedicated to a series of paintings and drawings of her children. Many are from private collections and have never before been exhibited to the public.

According to Yermakova, it is the joy and beauty of Serebryakova’s paintings that have made her so popular. The artist’s brush could give everyday scenes an epic, almost ephemeral quality.

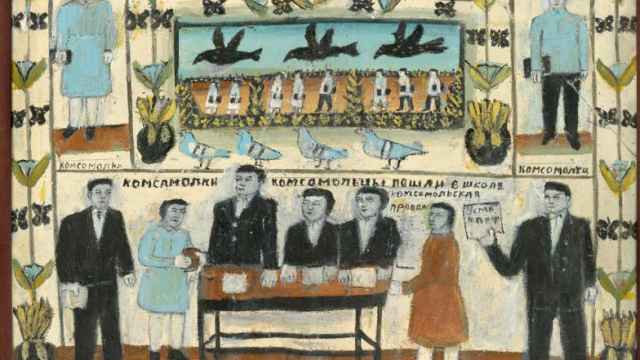

But the “happy years” couldn’t last. As with many others, the Revolution proved to be a seismic event for Serebryakova.

During the unrest, her family estate in Neskuchnoye—near Kharkiv, Ukraine— was plundered and burnt down, along with many of her artworks. Her husband was arrested and died in 1919 of typhus, which he contracted in a Bolshevik jail. Serebryakova suddenly found herself widowed and the sole breadwinner for four children, as well as for her ailing mother.

She was forced to move to Petrograd—

present-day St. Petersburg—and swapped

oil paints for more affordable materials like

pastel and charcoal.

Struggling to find work, she accepted a commission in Paris in 1924 with the plan of earning some quick money. However, the Soviet authorities prevented Serebryakova from returning home. She was able to bring her two youngest children to live with her in France, but the older two remained in Russia.

Life wasn’t easy for Serebryakova in Paris, She admitted that she struggled creatively abroad and longed for her homeland and family.

Yermakova chose Serebryakova’s monumental canvas ”Bleaching Cloth” (1917) as the centerpiece of the exhibition. In it, peasant women at work are framed majestically against a low horizon. Smooth lines and a tranquil stateliness imbue the simple scene with an epic meaning.

“It’s one of the last paintings she completed

at Neskuchnoye in 1917,” says Yermakova.

“It was the year of the revolution and the big,

happy peasant world so admired by Serebryakova

was about to change forever.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.