“I am the director of a very influential museum. I believe that everything that happens here is our sphere of influence, and a very powerful one at that,” says Marina Loshak, the director of the Pushkin Museum, sipping green tea.

We sit in her spacious office, next to a unique replica of an Italian Renaissance-era courtyard inside Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. In the center of the courtyard stands a huge statue of Michelangelo’s David, poised to attack Goliath. It’s a replica. By combining copies with originals, Pushkin Museum has always seen itself more as a space devoted to culture in a broader sense than a museum collection.

Built by Roman Klein, a popular early 20th-century architect, the Pushkin Museum is an architectural landmark and a magnet for the Moscow intelligentsia. Yet, despite its extensive collection, the Pushkin Museum has always played second fiddle to St. Petersburg’s Hermitage.

In reality, however, the museum was never trying to compete. While Russia spent much of the 20th century sealed off behind the Iron Curtain, the Pushkin Museum served as a window into Western culture. For many Muscovites growing up in the Soviet Union, the Pushkin Museum was a genuine “temple of art.” Students learned history in its halls devoted to Ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt. Artists studied copies of Renaissance sculptures.

Now that the Iron Curtain is gone, the Pushkin Museum’s role is changing. It puts a much stronger emphasis on exhibitions, while also trying to showcase its own collection. At the same time, the educational program is still central to the museum’s mission.

“I don’t know another museum that has so many educational activities,” says Loshak: “From classes for small children —and we teach around 3,500—to lectures and workshops.”

Battle lines

Loshak took the reins less than four years ago, during troubled times for the Pushkin Museum. Her predecessor, Irina Antonova, still remains the museum’s president at the age of 95, after serving as director for half a century. The museum practically revolved around Antonova, so it was difficult for anyone to fill her shoes.

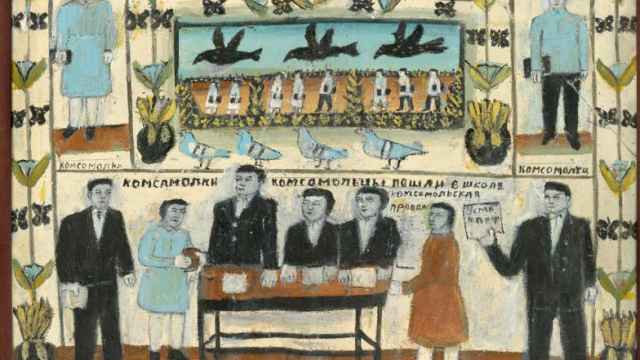

To complicate matters, in 2013 the museum was also embroiled in a bitter battle with the Hermitage. Antonova was trying to resurrect the idea of the Museum of New Western Art, which existed in Moscow from 1923 to 1948 as part of the Pushkin Museum.

The Museum of New Western Art housed the art collections of pre-revolutionary entrepreneurs Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov. After World War II, this branch of the Pushkin Museum was closed to stop “the spread of decadent bourgeois art.” Its priceless collection was split between the Hermitage and the Pushkin Museum. Antonova sought to reunite it.

The quest to reestablish the Museum of New Western Art pitted Antonova against Mikhail Piotrovsky, the head of the Hermitage, and relations between the two leading cultural institutions in the country soured to the point that President Vladimir Putin had to get involved to mediate the situation.

Loshak opted to stay friends with the Hermitage and its director: “The Pushkin Museum can’t live without the Hermitage and vice versa,” she says. “Compromise is the only way.”

This town is big enough for the both of us

Loshak comes from a very different background than Antonova. A professional linguist, she started her museum career in her hometown of Odessa, Ukraine.

After moving to Moscow she worked at several galleries, including the Tatintsian Gallery and the Prone Gallery at Vinzavod, one of the first renovated industrial spaces in Moscow. She was then appointed head of the new Manezh exhibition complex and turned it around in just a year. Today, Manezh is one of the city’s top exhibition spaces.

So far, Loshak’s tenure at the Pushkin Museum has also been a success. The museum recently succeeded in collaborating with the Hermitage on the “Icons of Modern Art” exhibition at Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris, where the two parts of Sergei Shchukin’s collection were reunited for the first time.

“That exhibition broke the record for number of visitors. Around 1.25 million attended it,” says Loshak, visibly excited.

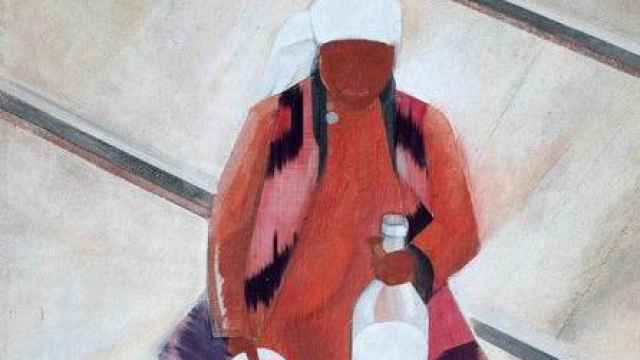

Under Loshak, the Pushkin Museum has considerably increased the number and range of its exhibitions, which have featured artists from Raphael to Paul Klee and from Piranesi to Alexander Rodchenko. In 2016 the museum held an astounding 44 exhibitions, while the total number of visitors soared to 1,133,200, up by 12 percent from the previous year.

“We have to take into account the mindset of a big city resident today: They only want to see something new,” says Loshak. The most popular exhibit of 2016 was “Raphael: Poetry of the Image” with paintings from the Uffizi Gallery and other Italian collections. Over 200,000 people came to see it.

For Loshak, it is difficult to name one favorite exhibition— they were all devoted to very different themes, she says.

“I can’t say if I love the Italian Renaissance from Bergamo exhibit more than I love the art of raku, traditional Japanese pottery,” Loshak says. “All I can say is that none of the exhibitions were organized in haste or in a perfunctory manner.”

The most complex exhibition Loshak has worked on is one currently on display—“Facing the Future: Art in Europe, 1945–1968.”

“We started working on it almost from my first day in the office, collaborating with two European museums—the BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels, Belgium and the ZKM, Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany—and more than 50 partners, museums and private collections.”

Loshak believes that “1945–1968” has achieved its goal: reaching young people. “I thought about young artists when I was working on this exhibition,” she says. “And artists come here not once, but twice or even four times.”

Recently, the Pushkin Museum started hosting exhibitions of Russian artists, which was traditionally the domain of the Tretyakov Gallery, while the latter has organized several highprofile foreign art exhibitions.

Some even believe that the two museums are vying for the role of “number one museum” in Moscow. Loshak says that the Pushkin Museum is not afraid of competition: “In this huge city, there’s space for several more Tretyakov Galleries and Pushkin Museums.”

Museum quarter

Admiring the Neoclassical columns of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts’ main building, it’s hard not to notice the construction work being carried out on both sides of its lovely courtyard. These are the beginnings of the so-called “museum quarter,” which will soon transform the entire neighborhood.

The dream of a “museum quarter” was born a long time ago. Ivan Tsvetaev, the museum’s founder, talked about this expansion from the very start and was the first to use the catchphrase. His dream came true in 1961, when the Pushkin Museum acquired its first additional buildings in the neighborhood. Today, it has six buildings open to visitors.

In 2008, then-President Dmitry Medvedev decreed the building of a “museum quarter,” that would unite all the buildings into one complex. World-renowned architect Norman Foster was hired to work on this, but left in the early stages, and the project stalled. In 2013, Meganom, a wellknown Moscow architectural bureau, was chosen instead.

Loshak points to the walls around us. “This is an old building, it’s been through a lot and it’s tired,” she says. “It desperately needs renovation. We can’t even install an elevator for disabled people. All of this will change after the reconstruction.”

The work is already under way. The historical building of Vyazemsky-Dolgoruky will turn into the Old Masters Gallery by the end of 2018. The Prince Golitsyn family mansion, right behind the 20th-Century Art wing, was recently given over to the Pushkin Museum. After housing two video art exhibitions, it will be closed in April this year for reconstruction and will open its doors in 2019 as the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists’ wing.

In 2019, the “House of Text” will be inaugurated in the Stulov Brothers House, a former tenement building that will host all of the museum’s libraries, plus several exhibition spaces. The main building will be the last to be renovated, around 2019-2020. A historic gas station next to the 20th-Century Art wing will be preserved and turned into a box office. There will also finally be space for a proper museum store and cafes.

Completely new buildings will be built for the storage and restoration facility, and an additional exhibition hall will be constructed. All of the buildings, old and new, will be connected by underground tunnels.

Of course, there are budgetary constraints. Only half of the budget comes from the Ministry of Culture. The rest comes from other sources, mostly private donations from the friends of the museum.

“Sometimes we receive new artworks,” says Loshak. “[Oligarch]

Alisher Usmanov gave us a portrait by Frans Hals, an

important work, and we also got two Sumerian objects recently

and two pre-Columbian jugs from Mexico.”

New horizons

The Pushkin Museum has also been gaining influence abroad. In 2017, it will take part in the Venice Biennale, one of the world’s biggest contemporary art events, for the first time. But the museum’s clout doesn’t just come from exhibitions.

“What also matters is the atmosphere that has developed over the decades, attracting intellectuals, liberals, and freethinkers to the Pushkin Museum,” says Loshak.

“New Pushkin” is an initiative at the museum to present new artists, not just those working with painting or photography, but those using various new media as well. Video art, as well as sound art and performance can be introduced in the context of a traditional museum.

“A contemporary museum is not just art that’s hanging on the walls—it’s a space for dialogue between the visitor and the works he sees,” says Loshak.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.