Last year’s “To Be Left Until Called For” exhibition at the Jewish Museum was one of Moscow’s most popular art shows in 2016. Drawing together more than 100 avant-garde paintings from museum collections around Russia and uniting them for the first time, the exhibition was inspired by the publication of the third and final volume of the Encyclopedia of Russian Avant-Garde — written by the exhibition’s curator, Andrei Sarabyanov.

One of the highlights of the show was the inclusion of several previously unknown paintings by key artists that were discovered in the course of research, including a canvas by suprematist avatar Kazimir Malevich.

So it is no surprise that the second instalment of the exhibition, titled “Upon Request,” has generated so much anticipation. Last week’s opening drew large numbers of viewers eager to be among the first to get a glimpse of these rare works. However, perhaps because the new show cannot boast any of the high-profile finds uncovered for the first exhibition, it has attracted slightly less attention.

“There are no discoveries here like there were at the first exhibition,” Sarabyanov told The Moscow Times. “But here there are more than 20 artists whose works have never been exhibited anywhere. This to me is the greatest discovery of this exhibition.”

“It’s incredible that to this day you can hold an exhibition like this, where nobody knows anything about half of the artists,” he said.

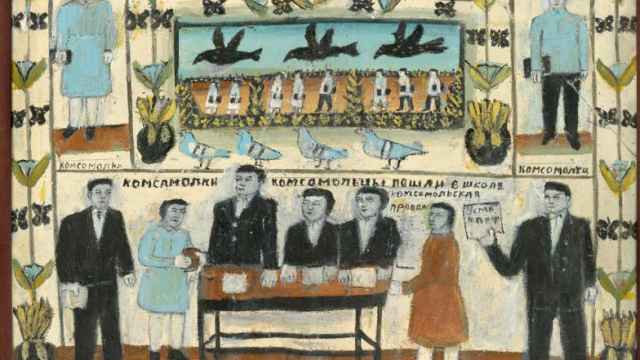

While the 2016 show introduced viewers to paintings from before the revolution, “Upon Request” tracks the development of the Russian avant-garde movement from 1917 to the mid-1930s. The early works were originally distributed to regional museums at the beginning of the 1920s, intended to be used to educate a new generation of artists. Others arrived in the provinces later, as the authorities began to turn against avant-garde art in favor of the safer, more ideologically sound Socialist Realism.

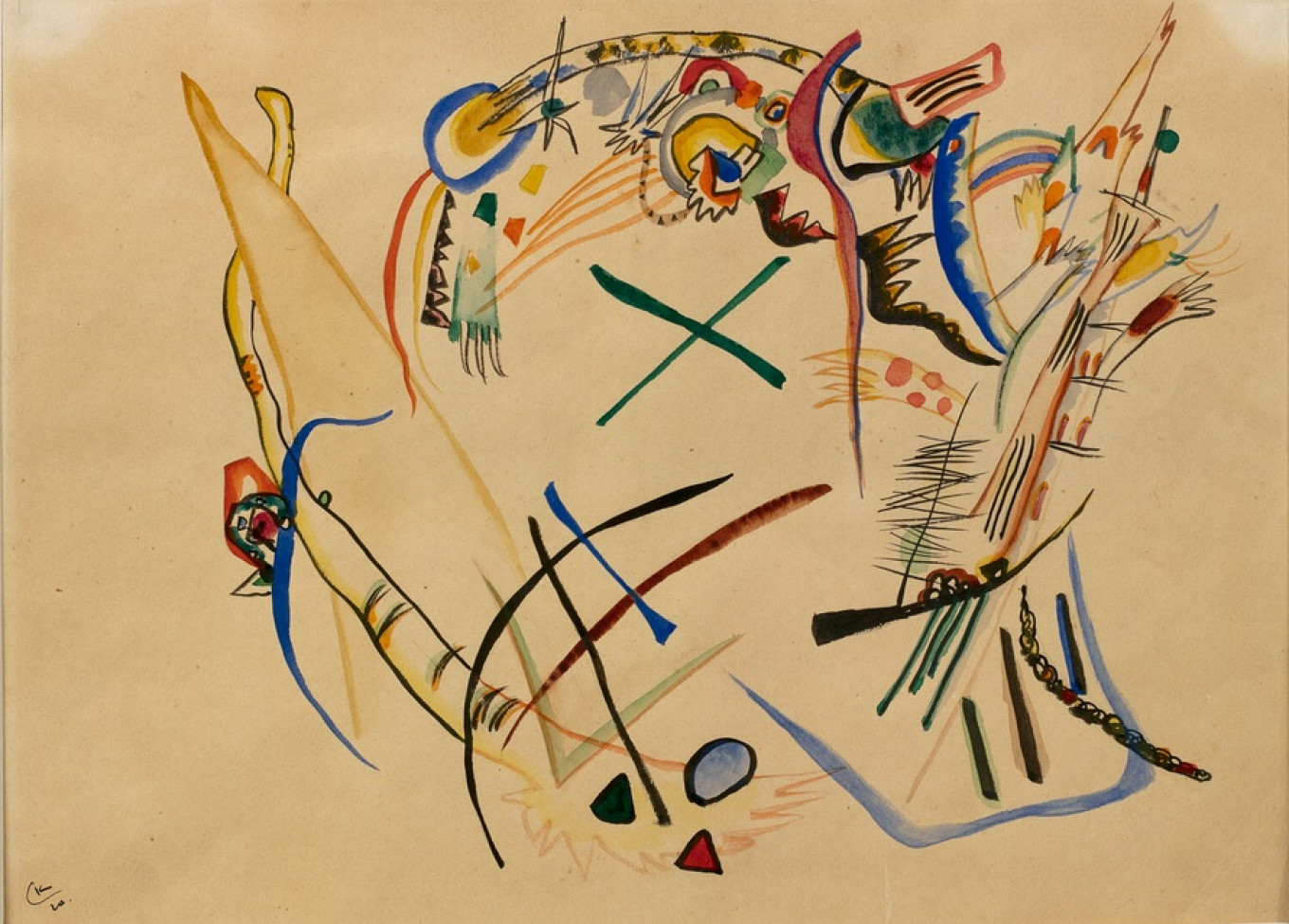

Key artists featured include Alexander Rodchenko, Wassily Kandinsky, Ivan Klyun and Gustav Klutsis, but the real emphasis here is on the remarkable quality of the forgotten artists, like Nikolai Goloshchapov, Olga Deineko and Fyodor Zakharov.

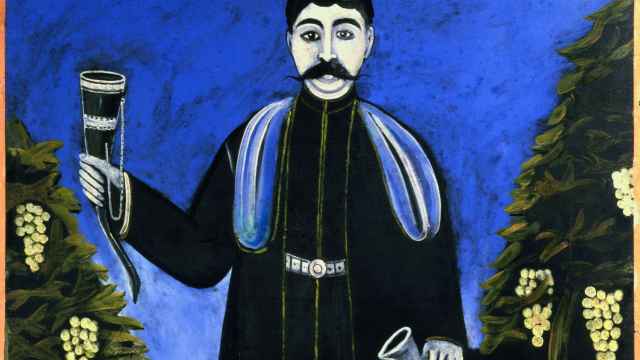

The sheer diversity of the country is evident in the subject matter, which moves from the planes and still lifes of Constructivism and Purism to the more figurative representations of Primitivism and Expressionism and the bold, loose brushstrokes of Late Cezannism. As the harsh lines of Cubism and Suprematism soften, we see city scenes in Moscow and Omsk, courtyards in Dagestan and windswept fields (Grigory Borisov’s “Haymaking”) and lyrical landscapes (the swirling motion of Goloshchapov’s trees and billowing land in “Landscape”).

Unsurprisingly, the characters are workers and peasants. There are nods to Malevich (Palmov’s “Family of a Peasant Farmer”) and Picasso, but one of the striking qualities on show is, as Sarabyanov puts it, the “Frenchness” of the work. Alexander Volkov’s “Noon in Shakhimardan” is almost Gauguinesque in its approach to a group of Uzbek peasant women, with their ruddy complexions, olive skin and bright clothes.

Sarabyanov is at pains to point out that Russian avant-garde was never truly a Soviet style, despite its frequent depiction in the West as something inseparable from the USSR. He stresses that, as the exhibition proves, the avant-garde artists “had achieved almost everything they needed to” before 1917, and that the movement was essentially in slow decline from then onward.

Sadly, many of the artists exhibited here were later executed or ended up in labor camps. In some cases, barely a trace of the work they created remains for contemporary scholars and art lovers to enjoy, with the fate of their paintings, so radical for their time, a mystery.

The works are displayed on three sides of a black-walled square room, a format resembling that used at exhibitions in the early 20th century. Looking even further back, it is also a knowing nod toward the displays of art held by the Salon: The paintings hang cheek by jowl in uneven, multiple tiers, each illuminated from above by a lamp.

While such dedication to historical accuracy is laudable, this worthy endeavor does create unfamiliar problems for viewers. One woman complains that some of the upper paintings “aren’t visible at all, you need to stand back to see them.”

But despite the dim lighting and the rubber-necking — and keen eyesight — required to admire the higher paintings, it is rewarding to see them in something approaching the aesthetic context in which they were originally displayed. This curatorial boldness ultimately comes up trumps: It goes a long way to genuinely recreating for viewers the atmosphere and context in which these paintings would have originally been seen.

As for the criticism, for Sarabyanov this is a sign that the art is still relevant: “When these artists first exhibited their works, there was also much in the way of criticism,” he said. “And here — it’s a sign that this art is still alive.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.