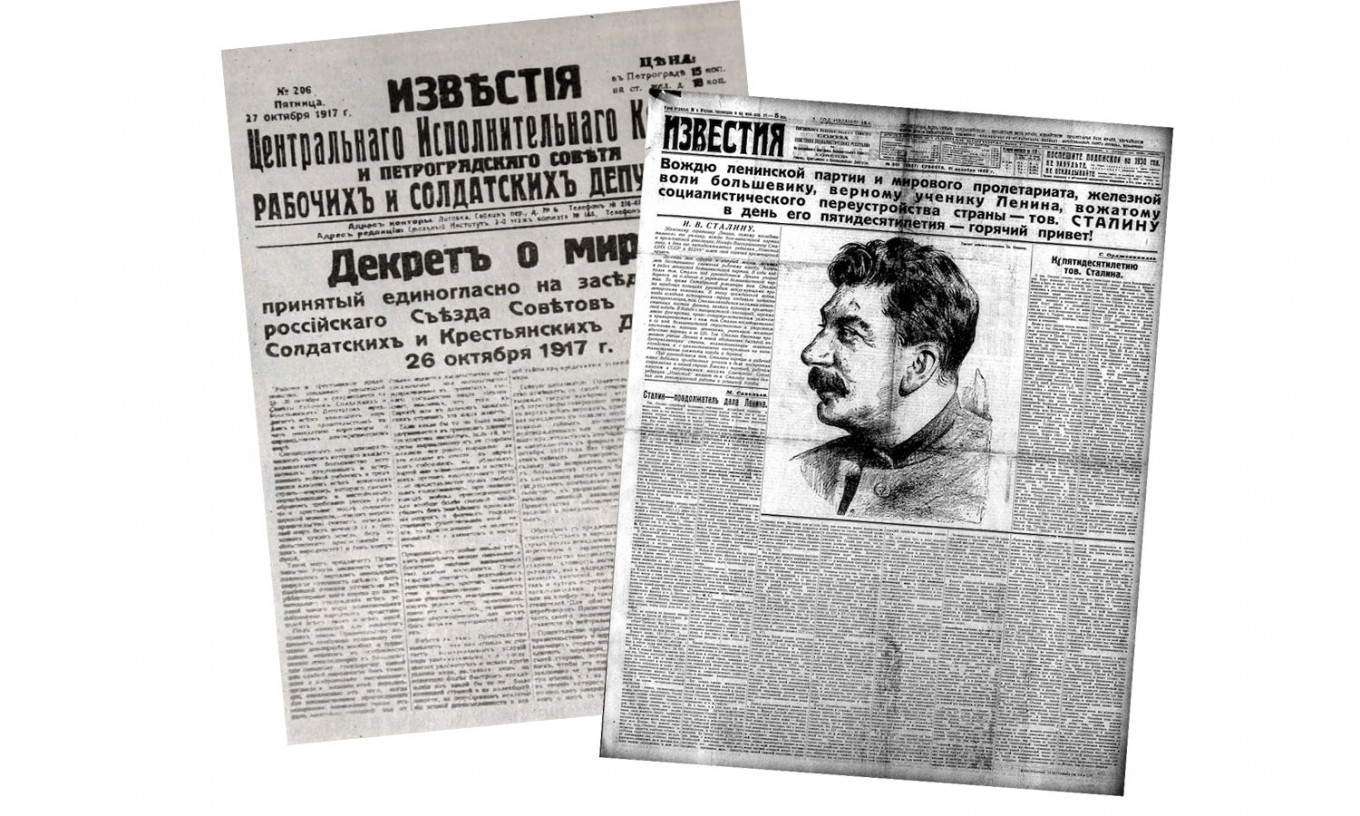

Izvestia was born in the midst of Russia’s March 1917 revolution.

As fighting raged in the streets of Petrograd (today’s St. Petersburg), a small group of revolutionaries seized a printing office and changed Russian journalistic history. That night, they started to work. “We got down to writing,” Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, a Bolshevik and close associate of Lenin who was one of the leaders of the group, recalled in his memoirs. “Everyone penned a few articles... Everything we wrote we read out to each other straight away and then, without any self-importance, discarded the worst.”

As dawn broke on March 13, 1917, the printing press began churning out the first 100,000 copies of Izvestia. “We breathed happy sighs of relief, shook each other by the hand and congratulated each other on the revolution,” Bonch-Bruevich recalled. Two days later Nicholas II, Russia’s last tsar, would abdicate.

Now, as Russia commemorates 100 years since the tumultuous events that swept away the monarchy and paved the way for the Bolshevik seizure of power, Izvestia is marking its centenary. No other Russian newspaper has been in continual publication for so long.

Izvestia’s story—through both its journalism and the fate of the paper itself — is the story of the Soviet Union and the independent Russia that emerged from the collapse of Communism.

From a small revolutionary rag, Izvestia became the official publication of the Soviet government with thousands of employees and it built its iconic editorial offices in the constructivist style, during the tumultuous 1920s, on Moscow’s central Pushkin Square. A leading proponent of reform in the 1980s, Izvestia re-invented itself as a democratic broadsheet after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Under President Vladimir Putin, Izvestia has seen its influence collapse as short-lived editors and a strong pro-Kremlin editorial line hollow out the once influential publication.

“You feel the responsibility. You feel the baggage of history and tradition,” Izvestia Deputy Editor Sergei Koroteyev said in an interview in the newspaper’s offices.

Leading Editors

Throughout the Soviet era, Izvestia’s chief competitor was Pravda, the mouthpiece of the Communist Party. But Izvestia, officially the publication of the revolutionary councils called Soviets, always enjoyed greater editorial freedom—as far as was possible in an ideological monopoly—and represented the more liberal, progressive political forces against Pravda’s conservative stance.

Perhaps its most famous editor was Nikolai Bukharin, the revolutionary theorist and Soviet politician who joined with Stalin to oust arch-rival Trotsky—only to be pushed out, in turn, by Stalin. Despite his fall from favor, Bukharin’s appointment to Izvestia in 1934 gave him a degree of power. His U.S. biographer, Stephen Cohen, has written that Bukharin “acquired for the daily a reputation as the liveliest, most critical-minded of all Soviet newspapers.”

At the peak of the Great Terror, Bukharin was fired, convicted in an infamous show trial and executed — with all these events covered assiduously by his former newspaper. Bukharin was one of four Izvestia chief editors to die in Stalin’s repressions. His successor, Boris Tal, was in charge for just 10 months before he, too, was arrested, tried and shot.

When Nikita Khrushchev succeeded Stalin in 1953, he denounced the Soviet dictator and ushered in a period of political thaw. Khrushchev appointed his own son-in-law, Alexei Adzhubei, as chief editor in 1959. Proximity to Khrushchev made Adzhubei an immensely powerful political figure, coining the famous Russian phrase: “If you don’t have a hundred friends, marry like an Adzhubei.”

Coping with the newspaper’s Stalinist heritage was difficult. Under Stalin, the press had only one clear purpose: it was a tool for the demonization and denunciation of “enemies of the state.”

Immediately after arriving at the newspaper, Adzhubei made a series of format changes: photo spreads, first-person accounts, bold headlines, and even higher design standards. Instead of searching for enemies and glorifying the leadership, the paper introduced new sections focused on family and private life — revolutionary changes after Stalinism.

Another section, “The World of an Intelligentsia Man,” emphasized that Soviet society consisted not only of peasants and laborers. “Izvestia” was even allowed to question the efficiency of the nation’s economy and debate reforms.

Stanislav Sergeyev, a historian of Izvestia who spent 25 years working at the paper, described Adzhubei’s first day. “He arrived, looked at the most recent edition and, angrily threw it aside. ‘It’s not a newspaper,’ he said,” according to Sergeev.

Sergeyev, who was himself hired as a reporter by Adzhubei, recalled in an interview what it meant to be offered his first journalism job at the newspaper in 1960. “There was a phone call,” recalled Sergeyev, who was a student at Moscow State University’s journalism faculty at the time. “A voice said: ‘Listen, Stanislav, do you want to work in Izvestia?’ I could have fainted. Adzhubei was already at Izvestia and we had seen what it had become.”

Stagnation To Glasnost

Adzhubei’s tenure did not last long. He resigned in 1964 following the fall of Khrushchev and was stripped of his other official positions. Izvestia again became a more tightly controlled publication.

Together with Pravda, it was the butt of many jokes for its slavish toeing of the official line, particularly in the later Soviet period. One famous quip played on the literal Russian meanings of Pravda — truth — and Izvestia — news. “What’s the difference between Pravda and Izvestia?” the joke ran. “In Pravda there’s no news and in Izvestia there is no truth.”

But in fact, even during the period of Brezhnev’s stagnation, when there was very little room for maneuver, Adzhubei’s heritage still made itself felt. While Pravda provided a rock-solid, official Communist narrative and practically served as a set of life instructions for the party elite, Izvestia was still practicing more human approach, recalls the historian Nikolai Svanidze. “Its freer stance could be seen in its nuances: in style, implications, better writing, emotions that could break through the Soviet propaganda,” he says.

In the late 1980s, however, Izvestia once again returned to the

cutting edge of Soviet reforms and led the way in pushing back against

censorship. Journalists and editors were fierce champions of Gorbachev’s

policies of glasnost and perestroika.

In his memoir Power

Without Glory, former editor-in-chief Ivan Laptev described his first

battle with the censors several months after his 1984 appointment.

Despite receiving the go-ahead from Gorbachev and the head of the KGB,

the publication of “Reckoning” — an article about corruption in Moscow —

sparked a wave of anger.

“There was an avalanche of telegrams

and phone calls,” Laptev recalled. Soon, he was summoned to the offices

of several high-ranking officials who chewed him out over an article.

Such conflicts were extremely common in the 1980s.

“Nobody gave us glasnost or freedom of speech,” Laptev said. “We won them by fighting day by day, issue by issue and programme by programme.”

Putin’s Izvestia

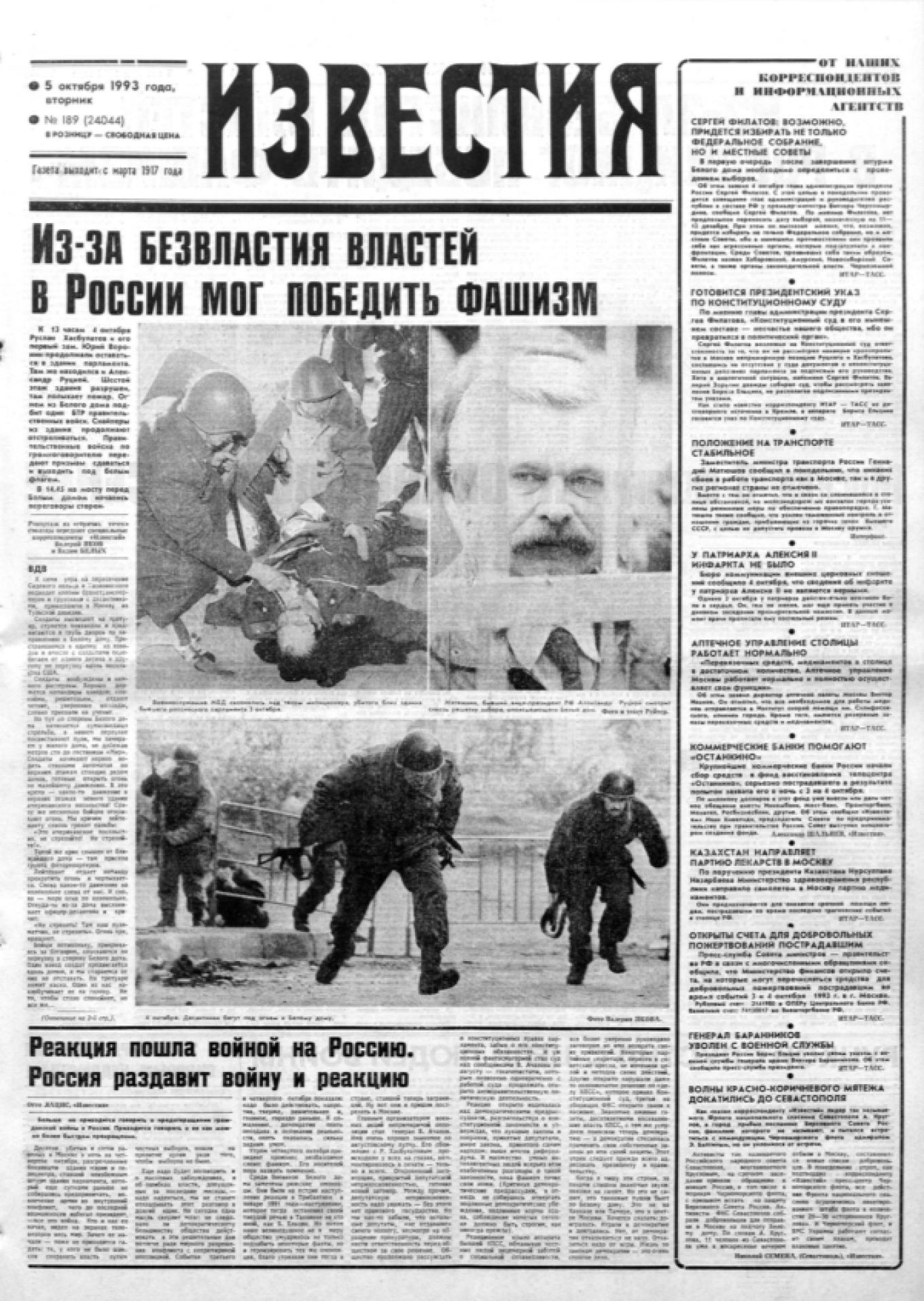

When Izvestia backed the plotters of a 1991 coup against Gorbachev, its staff revolted. Soon, editor-in-chief Nikolai Yefimov was forced out, ushering in another golden age for the newspaper.

“It was one of the most important newspapers in the 1990s,” says prominent Russian journalist Oleg Kashin, who briefly worked at Izvestia in 2004.

While Izvestia re-invented itself as a liberal outlet, its arch-rival Pravda failed to adapt to post-Soviet Russia and ended daily publication. Its main post-Soviet incarnation is the official mouthpiece of the Communist Party, a fringe and politically irrelevant publication.

Changes of ownership and political interference in Izvestia’s editorial line, however, gradually undermined its reputation. Raf Shakirov was appointed chief editor in 2003 but was fired the following year. The newspaper’s billionaire owner, Vladimir Potanin, had run afoul of the Kremlin over Izvestia’s vivid coverage of Chechen terrorists’ bloody seizure of a school in Beslan, a town in Russia’s North Ossetia region.

“The decision was political because it was obvious Putin’s ratings had fallen dramatically [over Beslan],” Shakirov said in a telephone interview. He said his ouster was the Putin-era Kremlin’s first major attack on the print media. Putin has been accused of cracking down on the Russian press and shuttering dozens of media outlets in his seventeen years at the top of Russian politics.

“A new epoch had begun: the rollback of democracy and what remained of Yeltsin’s reforms,” Shakirov said.

After Shakirov’s successor, Vladimir Borodin, left Izvestia, the paper increasingly adopted a pro-Kremlin angle. Journalistic standards declined and the publication suffered, like other print media, from online competition. In 2008, The National Media Group, a conglomerate owned by close Putin ally Yuri Kovalchuk, purchased the newspaper.

Under the subsequent stewardship of Aram Gabrelyanov, a tabloid pioneer, the newspaper became the print equivalent of Russia’s muckraking, pro-Putin Life News website or the similarly sensationalist NTV television news channel. It became famous for its extremist columnists, political hit jobs and leaks from the security services.

In one characteristic incident in November 2015, U.S. Embassy in Moscow mocked Izvestia for an obviously forged letter it provided as evidence in an article claiming that the U.S. paid gay rights activists to smear Russian officials. U.S. diplomats circulated a “corrected” version of the short letter that highlighted at least 25 spelling and grammatical mistakes.

Gabrelyanov, who declined to be interviewed for this article, was sacked last year. The newspaper is now on its 9th chief editor in 14 years and has a print run of only 72,000 —less than the 100,000 of the very first edition and a far cry from the 8 million during its heyday. Staff say its online audience is growing, and deputy editor Koroteyev insists that it remains one of Russia’s most respected newspapers. But the Izvestia of 2017 is a shadow of its former self, when it set the news agenda for a sprawling Communist empire and its chief editors were confidants of the Soviet leadership.

“The newspaper has clearly exhausted its brand and its resources,” says journalist Kashin. “I would not be surprised if it shut-down. I’m not sure I would even notice.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.