The Moscow Times and Project1917 bring you the next installment of the most compelling stories of 1917. In the fifth episode of our series which takes place this week one hundred years ago this week, we meet Leon Bakst’s assistant, the leader of the Mensheviks bets Trotsky won’t last in New York, the Tsar turns a blind eye to the revolution looming.

February 20

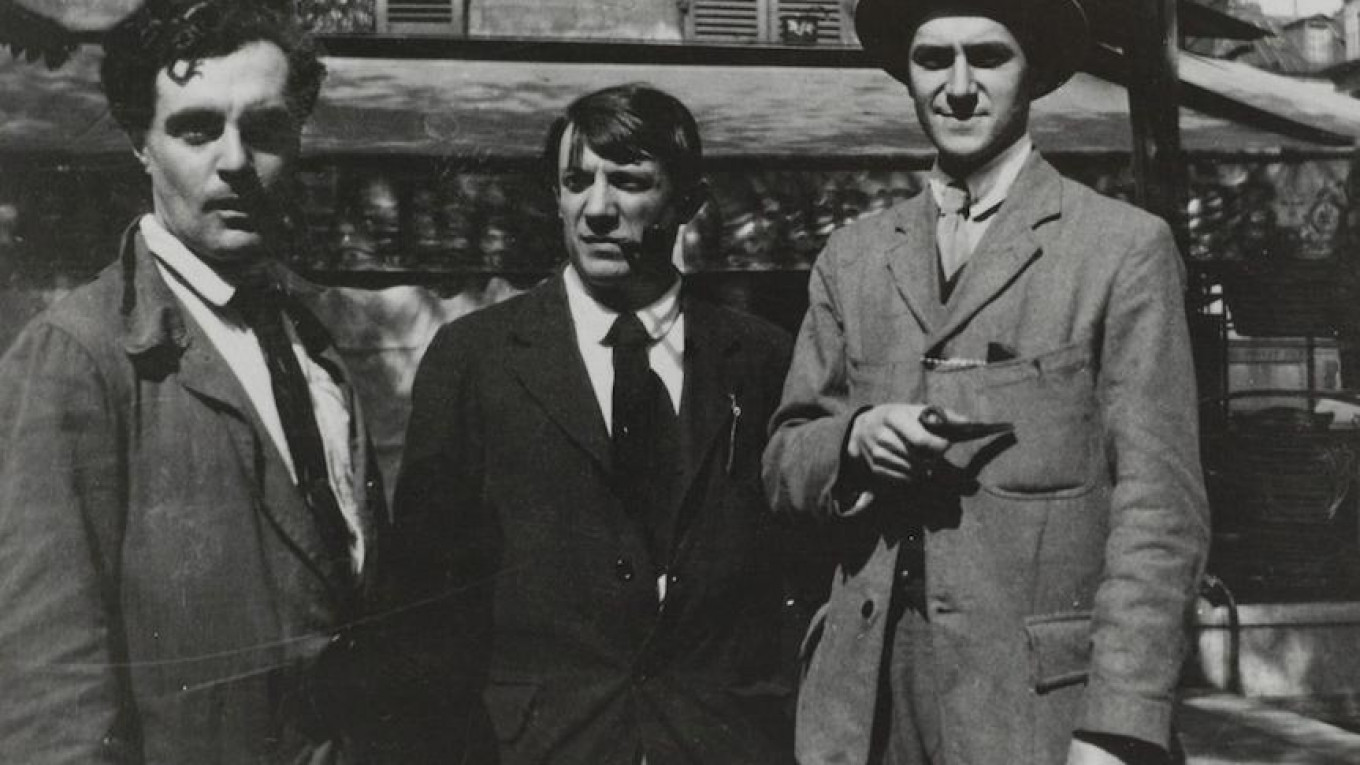

This is the young Spaniard hired to assist the famous Leon Bakst. They are going to work on decorations for new Russian ballets in Rome and Paris. As choreographer Leonid Massine puts it:

Many have heard of the young Spaniard who painted the dancers and helped Bakst to paint some of the accessories used in the ballet.

February 22

The leader of the Mensheviks, Julius Martov, bets in a letter to a friend that Trotsky won’t last long in New York. “I’d wager that within three months he’ll have quarreled with the American socialists and gone off to form his own splinter group.” His prediction was close. Here’s Trotsky on American socialists:

The ideas of the Socialist party of the United States lagged far behind even European patriotic Socialism. In the United States there is a large class of successful and semi-successful doctors, lawyers, dentists, engineers, and the like who divide their precious hours of rest between concerts by European celebrities and the American Socialist party.

Their attitude toward life is composed of shreds and fragments of the wisdom they absorbed in their student days. Since they all have automobiles, they are invariably elected to the important committees, commissions, and delegations of the party. It is this vain public that impresses the stamp of its mentality on American Socialism. My first contact with these men was enough to call forth their candid hatred of me. My feelings toward them, though probably less intense, were likewise not especially sympathetic. We belonged to different worlds. To me, they seemed the most rotten part of that world with which I was and still am at war.

February 23

Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, the Tsar’s uncle and close friend, describes his last attempt at convincing Nicholas II to open his eyes to the revolution. This one is a long entry, but it’s worth it — it’s one of the most dramatic episodes of this year full of drama.

I

finally got an invitation from Alex for breakfast in Tsarskoe Selo.

Those breakfasts! It seems half a year of my life has been lost at

breakfast in Tsarskoye Selo! Alix was in bed and promised to see me as

soon as I was done eating. There were eight of us at the table: Nicky,

myself, the Heir, the Emperor’s four daughters and an aide-de-camp. They

were all in good spirits and completely ignorant of political events.

We drank coffee in the violet parlor. Nicky went into the adjoining bedroom to inform Alix of my arrival. I briskly went in. Alex was lying in bed in a white lace peignoir. Her beautiful face was serious, and it didn’t suggest anything good. I realized that she suffered from the attacks. This upset me. After all, I was there to help, not harm. I also didn’t like how Nicky looked as he sat on the wide bed. In my letter to Alix, I stressed the words: "I want to see you completely alone so we can talk face to face." It was uncomfortably difficult to rebuke her for dragging her husband into the abyss in front of him.

I kissed her hand, and her lips barely touched my cheek. It was the coldest greeting she’s ever given me since the first day we met in 1893. I took a chair, pulled it close to the bed and sat opposite the wall covered with countless icons illuminated by blue and red lamps.

I started by pointing to an icon and I said that I will speak bluntly to Alix. I briefly described the general political situation, and stressed the fact that the revolutionary propaganda has penetrated into the very heart of the population and that they accepted all the slander and gossip as truth.

She sharply interrupted me:

— It’s not true! The people are still loyal to the Tsar. (She turned to Nicky). – Only the traitors in the Duma and in Petrograd society are my and his enemies.

I agreed that she was half right.

— There is nothing more dangerous than half-truths, Alix, — I said looking her straight in the face. — The nation is faithful to the Tsar, but the nation resents the influence Rasputin had. Nobody knows better than me how much you love Nicky, but I still have to admit that your intervention in state affairs brings harm to Nicky’s prestige and to autocracy as a popular idea. Alix, I have been your true friend for twenty-four years. I still am your loyal friend, and as such I want you to understand that all classes of people in Russia are hostile to your policy. You have a wonderful family. Why don’t you focus your worries on that and give your soul peace and harmony? Leave the affairs of the state to your husband!

She became incensed and looked at Nicky. He said nothing and continued to smoke.

I continued. I explained that, no matter how much I was an enemy of the parliamentary form of government in Russia, I was convinced that at this dangerous moment if the Emperor formed a government acceptable to the State Duma, then this action would reduce Nicky’s responsibility and make things easier for him

— For God's sake, Alix, don’t let your infuriation at the State Duma prevail over common sense. A radical change in policy would alleviate the people's anger. Don’t let that anger explode.

She smiled with contempt.

— Everything you say is ridiculous! Nicky is the Autocrat! How can he share what is his divine right with anyone?

— You're wrong, Alix. Your husband stopped being Autocrat on October 17, 1905. Then was the time to think about his “divine right.” Now –alas — it’s too late! Perhaps after two months there won’t be anything left to reminds us of the autocrats, who have sat on the throne of our ancestors.

She muttered something and then suddenly raised her voice. I followed her example. It seemed to me that I needed to change my manner of speaking.

— Don’t forget, Alix, I was quiet for thirty months. — I shouted in a terrible rage — I didn’t say a word for thirty months about what was going on in our government, or, more correctly, your government. I see that you’re willing to die with your husband, but don’t forget about us! Do we all have to suffer because of your blind foolhardiness? You have no right to drag your relatives into the abyss.

— I refuse to continue this debate, — she said coldly. — You exaggerate the danger. You will see that I’m right after you calm down.

I got up, kissed her hand, and I didn’t receive the usual kiss in response, and left.

February 25

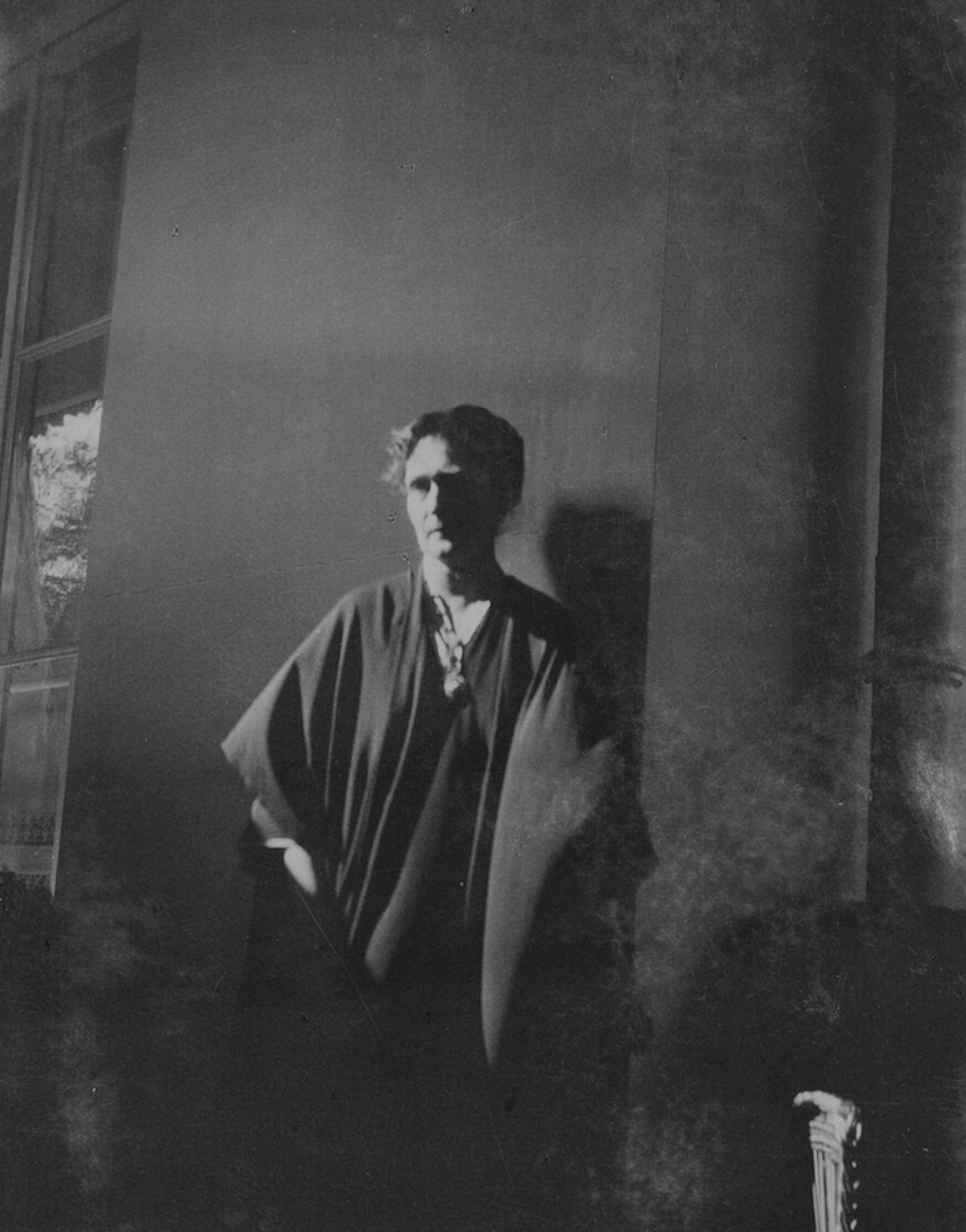

Olga Rozanova, one of the most prominent artists of the Russian Avant-Garde scene, has fallen in love with Russian folk songs. This is how they may have sounded.

“I have learnt a few folk songs and sometimes we get together and give them a bash. While I would hardly call my life monotonous, I am certainly working a lot, so I often get tired and am not feeling at my best. The cold weather continues to bear heavily on us. I will probably stay in Moscow over the summer, as I need to continue with my work. While it will almost certainly be hot and uncomfortable in the city, I really want to earn some more money.”

February 26

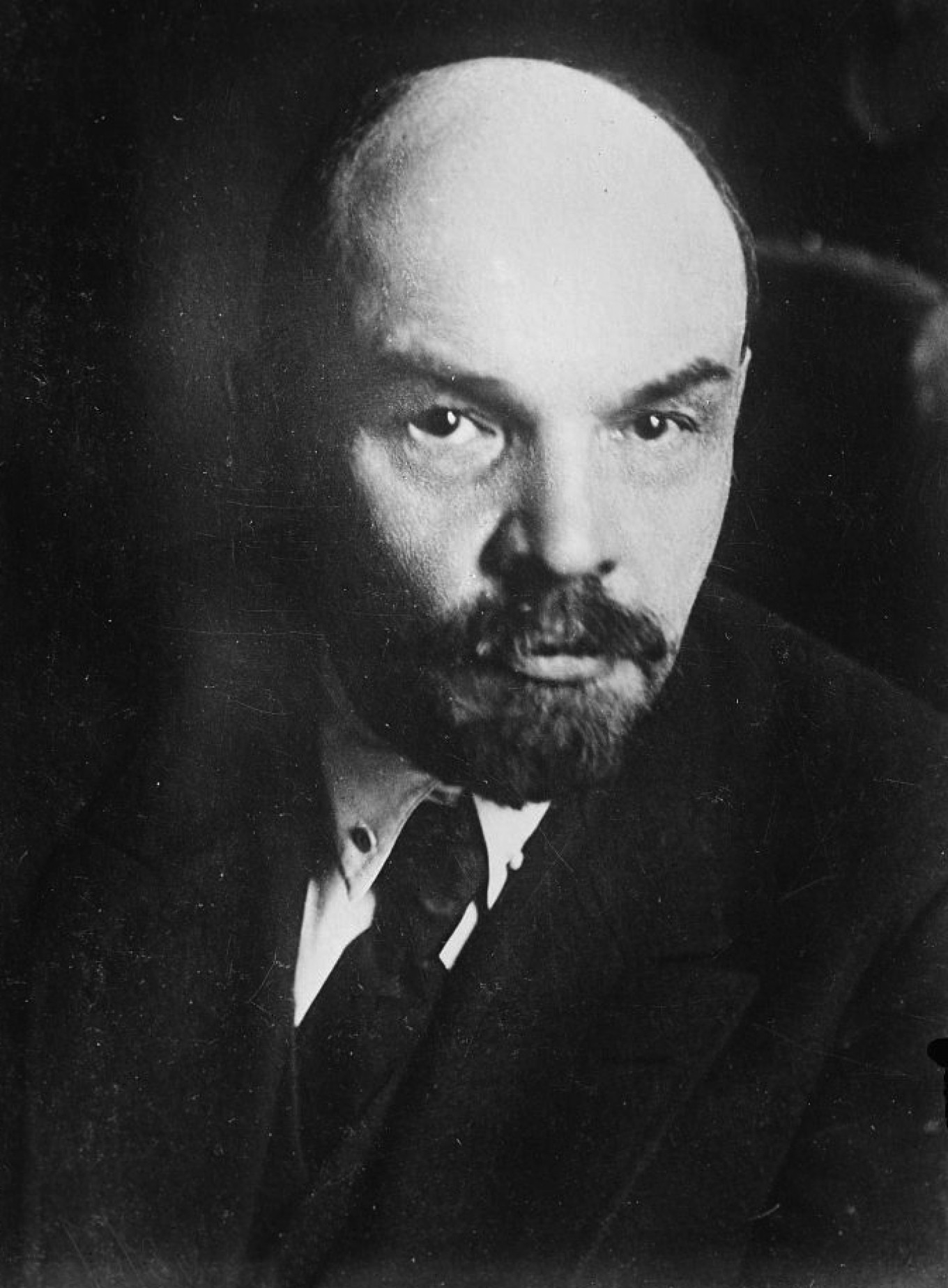

And finally, some advice from Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin who was living in exile in Switzerland at the time.

“We have got to come out as strongly and bluntly as possible against the ridiculous pacifism of the French (who believe socialism can be achieved without revolution) and their ridiculous belief in democracy.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.