The Moscow Times and Project1917 continue to share the most compelling stories of 1917. In the second instalment of this series, which takes place this week one hundred years ago, Lenin discusses Ukraine with a prisoner of war. British intellectuals, including Bertrand Russell, realize the enormity of events on the horizon. The atmosphere in the Tsar’s palace becomes increasingly foreboding.

January 30

1. An obscure Russian politician Vladimir Lenin is living in exile in Switzerland. He shares his observations on political intrigues, the ongoing war and his household affairs with his close friend and lover, comrade Inessa Armand.

Today, Lenin recounts his conversation with a prisoner of war, a Ukrainian peasant. They talked about relations between Ukrainians and Russians, German prison camps and the Englishmen, who “won’t give you a piece of bread if you won’t wash the floor for them.”

We were recently visited by two escaped prisoners of war. It was interesting to see “live” people, not corroded by emigrant life. One is a Jew from Bessarabia who has seen life, a Social-Democrat or nearly a Social-Democrat. He has knocked about, but is uninteresting as an individual because he is commonplace.

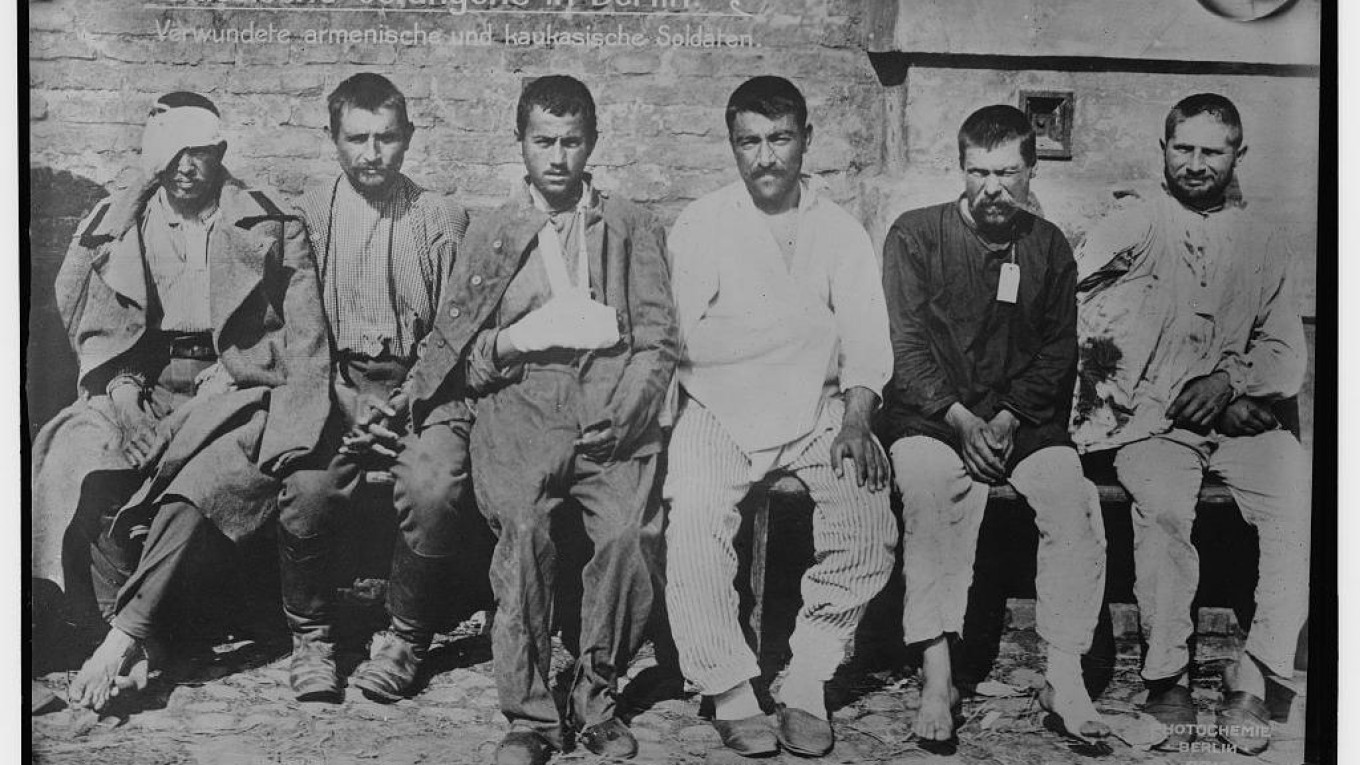

The second is a Voronezh peasant, a man of the soil, from an Old Believers’ family. A breath from the Black Earth. It was extremely interesting to watch him and listen. He spent a year in a German prison camp (a mass of horrors) with 27,000 Ukrainians.

The Germans build camps according to nations, and do their utmost to break them away from Russia; for the Ukrainians they sent in skilful lecturers from Galicia. The results? Only 2,000, according to him, were for “self-rule” (independence in the sense more of autonomy than of separation) after months of effort by the agitators!! The remainder, he says, were furious at the thought of separation from Russia and going over to the Germans or Austrians.

As regards the Tsar and God, all the 27,000, he says, have finished with them completely, as regards the big landowners too. They will return to Russia embittered but enlightened.

The Voronezh man yearns to get back home, to the land, to his farm. He traipsed around the German villages working, kept his eyes open and learned a lot.

They praise the French (in the prison camps) as good comrades. “The Germans also curse their Kaiser.” They hate the English: “Swelled heads; won’t give you a piece of bread if you won’t wash the floor for them” (that’s the kind of swine you get, perverted by imperialism!).

January 31

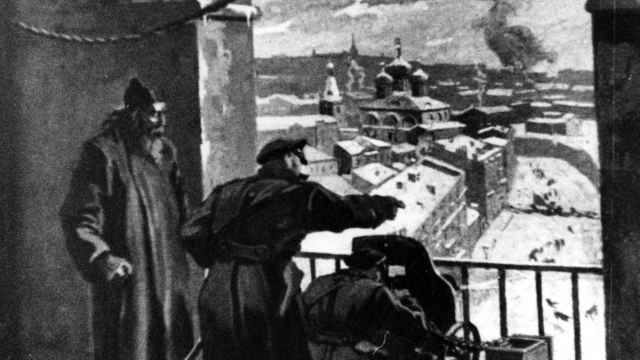

2. Disquieting rumours of unrest among the factory workers in Petrograd reach the palace. The head of the Tsar’s guard cites one of Nicholas II closest friends, admiral Nilov, who boldly declares: “there’ll be a revolution and we’ll all be hanged.”

The disturbing rumours have penetrated the walls of Tsarskoe Selo Palace as well. The atmosphere there was heavy. “It’s as if there’d been a death in the family,” remarked a frequent visitor. The Tsarina remained in bed almost the whole time. The children shot nervous glances at their parents. Trepidation reigned in the ranks of the closest courtiers, with certain ladies beset by presentiments of disaster. The faithful servant Admiral Nilov had long since lost faith in everything. Time and time again, he repeated to his friends, “there’ll be a revolution and we’ll all be hanged – and as for what streetlamps we shall dangle from, what does it matter?”

3.

By the beginning of 1917, the war has nearly stopped. Nobody wants to

risk starting another offensive. The frontline has remained unchanged

for months. Vladimir Dzhunkovskiy, one of the generals of the Russian

army, gives an account of what this strange war looked like:

In one place, there was a well right in the middle where the distance between us and the German trenches was no more than 30 steps. We and the Germans both had to use it since there wasn't any other.

The need for it was so great that there was a silent agreement between us and the Germans. Every morning the Germans went to fetch water first and then us, and there was never a single shot fired during this time, from our side or theirs.

February 1

4. This is the powerful account of Europe’s fate according to Morgan Philips Price, the Guardian correspondent (still known as the Manchester Guardian in 1917) in Petrograd:

For my part, living as I am on the threshold between east and west, I can look with dispassion on the ruin of European civilization and I am only surprised at the extraordinarily rapid rate at which it totters to its fall.

After all, it took the best part of 500 years for Rome and its civilization to decay, and even the Ottoman Empire in Europe has taken four centuries to recede. But now, in less than three years the lid has been torn off the whited sepulchre of Europe and within we see!

February 4

5. A young Bertrand Russell senses something cataclysmic approaching. Now we know that his dark premonitions would come true: over the coming years Russell would witness both “barbarism and petty war” and the fall of the capitalist system across Eastern Europe.

The existing capitalist system is doomed. Its injustice is so glaring that only ignorance and tradition could lead wage-earners to tolerate it. And I also feel no doubt that the new order will be either some form of Socialism or a reversion to barbarism and petty war such as occurred during the barbarian invasion.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.