As British Prime Minister Theresa May becomes the first foreign leader to meet U.S. President Donald Trump, the world waits to see just how close the U.S.-U.K. position on Russia will be. Traditionally, this Transatlantic “special relationship” has been marked by a shared view of the world. After the Brexit vote and Trump's election, however, the future of this relationship and so much else is now unclear.

Before departing for Washington, the British prime minister gave a speech suggesting that she hopes to base her relationship with Trump's America on the model enjoyed by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher at the end of the Cold War — the last time there was a non-traditional president in the White House and a female leader in Downing Street.

“When it comes to Russia, as so often, it is wise to turn to the example of president Reagan who — during negotiations with his opposite number Mikhail Gorbachev — used to abide by the adage ‘trust by verify.’ With President Putin, my advice is ‘engage but beware,’” May told journalists on Thursday. She went on to say that, in post-Crimea Europe, “we should not jeopardize the freedom that President Reagan and Mrs. Thatcher brought to Eastern Europe.”

So far, Donald Trump is showing few signs of being a Ronald Reagan, who was focused on defeating the power of the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

Nevertheless, as the historic meeting takes place, The Moscow Times looks back at how the leaders of these two world powers, the United States and Great Britain, have shaped the West's policy on Russia in years past.

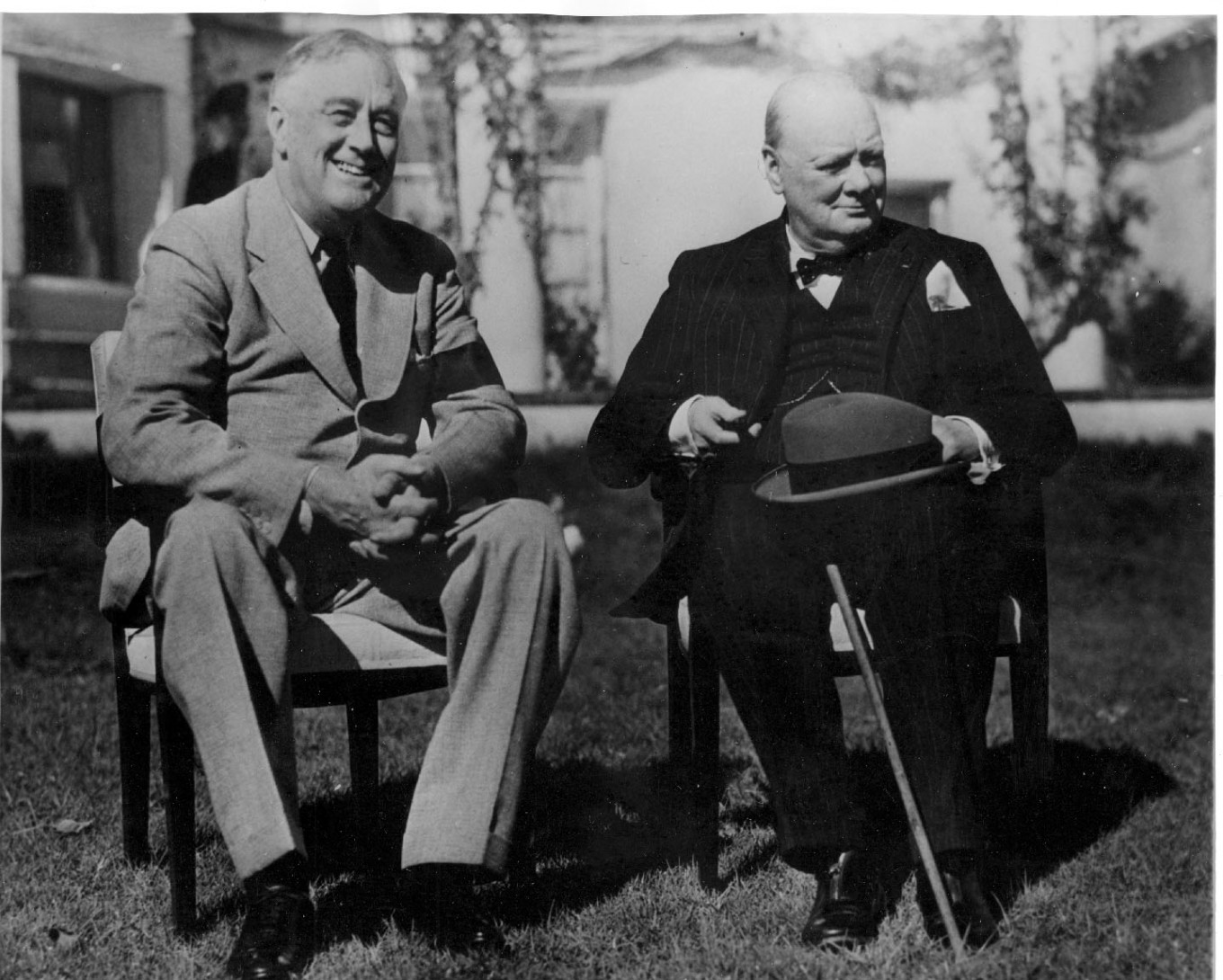

Roosevelt and Churchill

Donald Trump seems to prefer Winston Churchill over Ronald Reagan — so much so that he returned a bust of Winston Churchill to the Oval Office (a move many British

conservatives appreciated).

Perhaps that is a good sign for relations between London and Washington, as Churchill actually coined the term "special relationship." After the Yalta Conference, where Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin divided Europe into spheres of influence, the U.K. and U.S. led Western policy in the Cold War that followed.

In 1946, Churchill defined the “special relationship” in a speech at American University, describing the need for a “fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples” in opposition to the Soviet Union. “This means a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States,” Churchill said.

John F. Kennedy and Harold MacMillan

MacMillan, another conservative prime minister, enjoyed a close personal relationship with Democrat JFK during a time of escalating Cold War tensions. The pair spoke everyday during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.

The 1963 Profumo affair, in which the Secretary of State for War was forced to resign after his affair with the mistress of a Russian spy was exposed, shattered the government's reputation. This plot fascinated Kennedy, however, whom the same woman allegedly tried to court.

Lyndon Johnson and Harold Wilson

In the mid-sixties, the special relationship was under strain. Declassified documents reveal that the MI5 kept a secret file on Labor Prime Minister Harold Wilson throughout his time in office because of his supposed friendships with eastern European businessmen. The CIA also worried that Wilson had links to Moscow — fears that hawkish journalists in the U.S. often reported.

Wilson's decision not to send British troops to Vietnam strained tried with Washington, earning him a stellar reputation in the Soviet mass media. When Wilson asked to visit Washington, D.C., in 1965, hoping to act as a mediator in peace talks on the Vietnam War, President Lyndon Johnson refused, saying, "Why don't you run Malaysia and let me run Vietnam?"

Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher

This would be the Cold War “power couple,” uniting two people who described themselves as “ideological soul mates,” sharing a belief in low taxes, the free market, and strong national defense. Both leaders were committed to rejecting detente and determined to winning the battle of ideas against the Soviet Union. They kept in regular contact, using the famous “hot line” between the White House and Downing Street.

Bill Clinton and Tony Blair

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, American and British leaders started engaging with Russia. President Clinton, the first U.S. leader to meet with Vladimir Putin, once told a young Tony Blair that Vladimir Putin had “enormous potential.”

"We're trying to resolve this bilateral issue with Russia and kind of get this Chechnya thing resolved," Clinton told Blair on Oct. 13, 1999, referring to Russia's August 1999 airstrikes in Chechnya that escalated into the Second Chechen War.

In that same conversation, Bill Clinton shared some more thoughts about Putin's future: “His intentions are generally honorable and straightforward, but he just hasn't made up his mind yet. He could get a squishy democracy.”

George Bush and Tony Blair

George Bush is probably the U.S. leader that got closest to Vladimir Putin. Bush even said he once saw Putin's "soul." Tony Blair also praised the Russian president back then, saying Putin was an "impressive man with an impressive vision."

But relations soured again when Moscow invaded Georgia in August 2008.

The United States, Great Britain, and NATO called for a ceasefire by both Russia and Georgia. After Russian tanks moved into South Ossetia and Georgia, Bush announced U.S. humanitarian aid would be sent to Georgia. Washington also sent Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, which Moscow viewed as a hostile move.

Barack Obama and David Cameron

In the recent pre-Brexit and pre-Trump times, Barack Obama and David Cameron continued the traditional U.S.-U.K. relationship.

The pair led their countries during difficult times in Eastern Europe, following the war in eastern Ukraine and Russia's annexation of Crimea. Obama and Cameron were united in imposing economic sanctions on Moscow as a punishment for its actions in Ukraine.

Days before the Brexit referendum, Cameron addressed the press in one of his final bids to convince his countrymen to vote to remain in the European Union. “It is worth asking the question: who would be happy if we left? Putin might be happy," he said.

A few months later, in November 2016, after Brexit had passed and Cameron was gone from office, Donald Trump won the U.S. Electoral College and took the presidency.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.