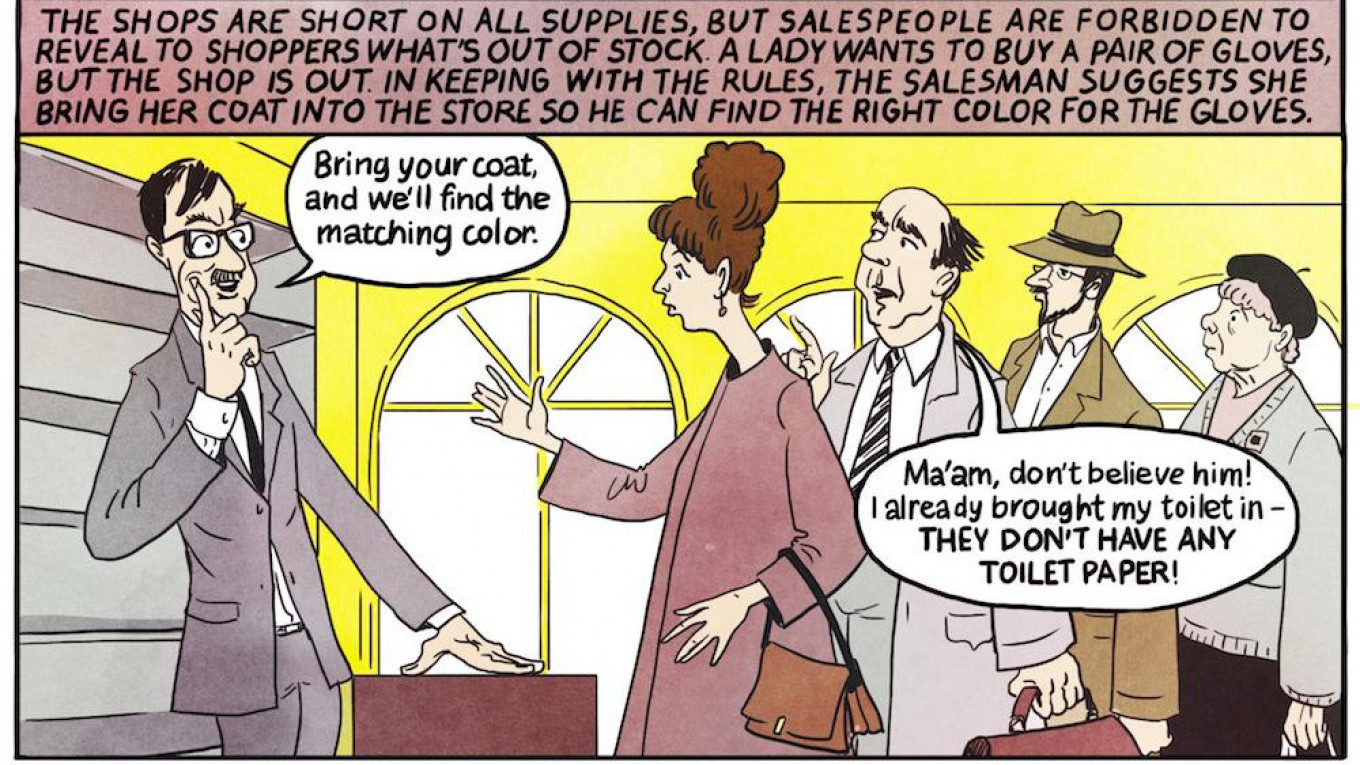

It’s a few months before the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, and the Soviet authorities are preparing to host guests from abroad. All the shops in Moscow have been instructed to never say no to a customer. A man is standing in line at a department store.

“I‘d like to buy a pair of gloves,” he says to the shop assistant. “Of course. Which size do you need?” “Nine.” “Oh, I’m sorry, we’re out of that size. What color would you like? Maybe we’ll find something.” “Brown.” “Oh, I’m sorry, we’re out of brown. Maybe you’d like to match your gloves to your coat? If you bring your coat to us, we’ll certainly find something.” The man behind him in the queue says: “Hey, don’t believe them, it’s all bullshit. I’ve already dragged my toilet bowl here and shown them my behind, but they’re yet to find any matching toilet paper.”

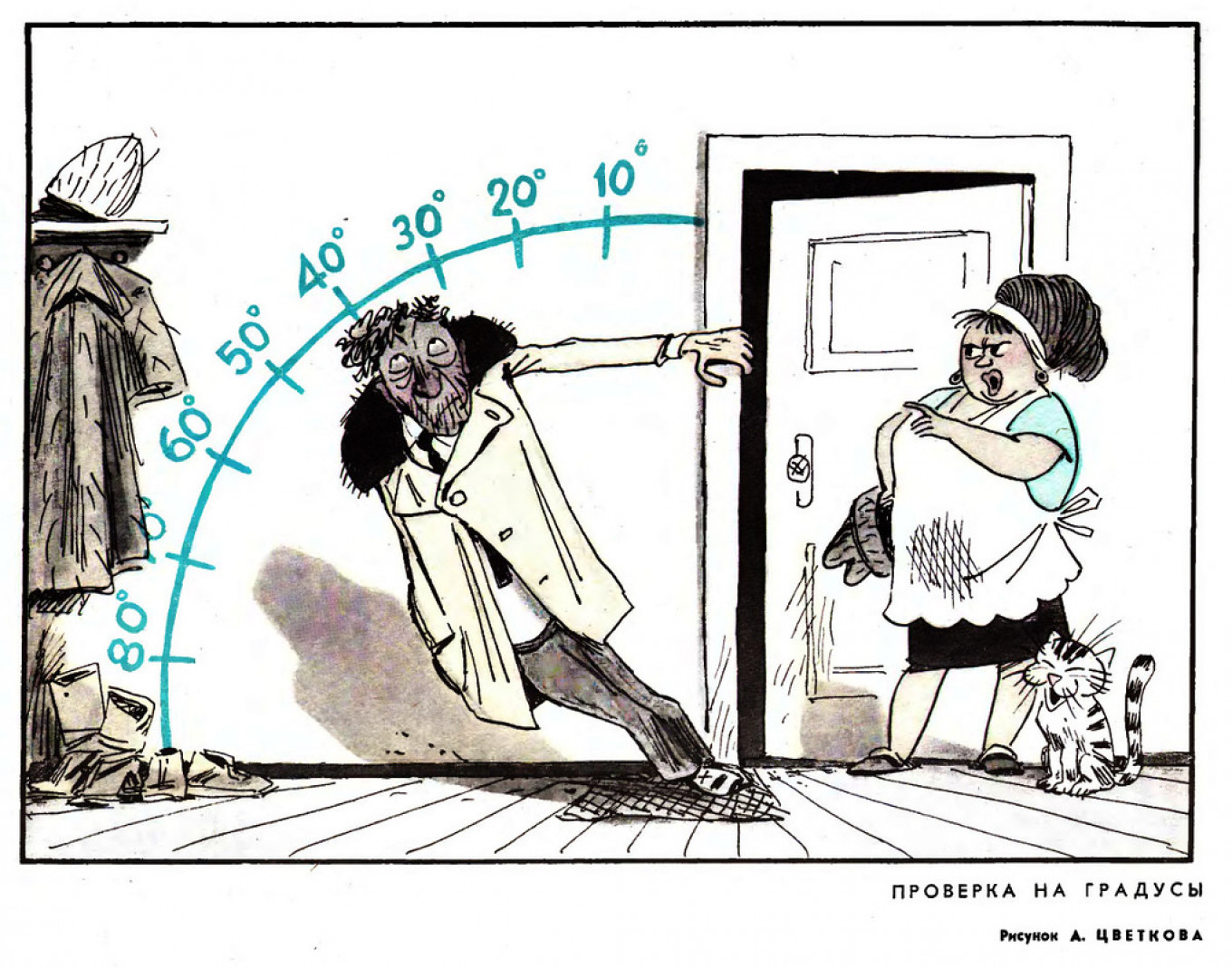

These were the jokes ordinary Soviet citizens told each other in the privacy of smoking rooms and cramped kitchens. There are thousands of them, yet they all touch on similar themes: repression, the scarcity of everyday goods, wars the USSR waged but disguised as “brotherly assistance,” Soviet leaders (from fiery but speech-impeded Lenin, to senile Brezhnev, and impotent Gorbachev), ethnic minorities and the silent majority.

In the years since they circulated among the proletariat, Soviet jokes have captivated academics and even piqued the interest of U.S. Presidents (Ronald Reagan was a famous fan, and the butt of many a joke). But as recently declassified CIA files show, foreign intelligence agencies also took a profound interest in them.

The recent “joke file,” released as part of a trove of declassified CIA files, is a paltry two-page PDF published on the CIA’s website. According to its masthead, the document was compiled at the request of the Deputy Director of the CIA’s office — and then, presumably, went to Ronald Reagan’s stand-up routine.

Most of the jokes are generic and common to the USSR, Poland, Czechoslovakia or Hungary: A man goes into a shop and asks: “You don’t have any meat?” “No,” replies the lady, “We don’t have any fish, it’s the shop next door that doesn’t have meat.”

Others are specifically Soviet in character — particularly those that stereotype ethnic minorities — and are traceable to the late 80s, the final years of the Perestroika and the Soviet Union itself:

“What’s the difference between Gorbachev and Dubcek [Alexander Dubcek, the Czechoslovak politician deposed during the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia who later supported the Velvet Revolution in 1989]? None, but Gorbachev doesn’t know it yet.”

Mikhail Melnichenko, Russian historian and folklore scholar, says some of the famous Soviet jokes were not Soviet at all. Melnichenko says one popular gag could be traced as far back as ancient Persia where it was used to ridicule a local tyrant. Jokes about food scarcity, similar to those of the Soviet genre, can be heard in Venezuela today.

Even though it lacks explanation and context, the jokes file still provides insight into how the Soviets tried to rationalize the baffling world of official doublethink. Ben Lewis, the author of “Hammer & Tickle,” who traveled across the former Eastern Bloc to research Communist jokes, formulated the “minimalist” and “maximalist” theories of humor under repressive regimes.

According to the maximalist theory, jokes were instrumental in the downfall of these regimes. The minimalist theory maintains that they were — at best — a way for people to vent after a long and grueling day at the factory or in a queue for the staples.

Melnichenko, author of a 1,100-page collection of Soviet jokes, prefers the minimalist joke theory. “Not every person who told these jokes was an anti-Soviet activist,” he told The Moscow Times. “It was a way to blow off some steam and discuss political topics in a way that the official discourse would not allow.”

“I treat these jokes as just one of the folklore genres — yes, highly politicized — but still employed as a means of entertainment, not a way to channel political discontent.”

Far more interesting, Melnichenko says, are the jokes that provide historical context. Here’s one of his favorites: Three prisoners meet in a transit camp. “I’ve been serving time since 1929 for calling Karl Radek a counterrevolutionary.” “I’ve been serving time since 1937 for failing to condemn Karl Radek as a counterrevolutionary.” “And I’m Karl Radek, nice to meet you.”

It’s ironic, says Melnichenko, that Russians have to study Soviet jokes declassified by the CIA. Russian secret services, which inherited vast archives from their Soviet predecessors, refuse to declassify them or open them to the public and researchers. There are still thousands of unheard jokes, overheard by informers or seized by authorities, buried in yellowing folders.

The Soviet authorities’ attitude towards jokes softened over the years. There was never a specific sentence or punishment for telling jokes, so they could be prosecuted under different sections of the Soviet criminal code.

In Stalin’s times, a joke could put you in a labor camp: “A judge emerges from a courtroom laughing. “What’s the matter,” a colleague asks. “Oh, I’ve just heard such a hilarious joke,” the judge says. “Tell it then,” the colleague responds. “I can’t,” says the judge, “I just gave some poor sod ten years for it.”

Later, in the post-war period, telling a careless jibe within earshot of an informer could probably cost you your job for “disseminating deliberately false insinuations about the Soviet state and society,” but it wouldn’t cost your life.

For many, the release of the U.S. Soviet joke files cast eerie parallels with contemporary Russia. No longer are citizens prosecuted for jokes as such. But, the number of prosecutions for “extremism” or “public incitement to violate the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation” (a charge reserved critics of Russia’s annexation of Crimea) has spiked since a package of new repressive laws passed during President Putin’s third term.

Today a meme shared on social media can — and does — result in fines and even prison terms. According to the SOVA Center, in 2010 there were six prosecutions for sharing “extremist” content on social media. That figure increased to 175 in 2015. The bitter joke in Russia today is: “My grandfather served time for telling a joke, I’m going to serve time for sharing memes.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.