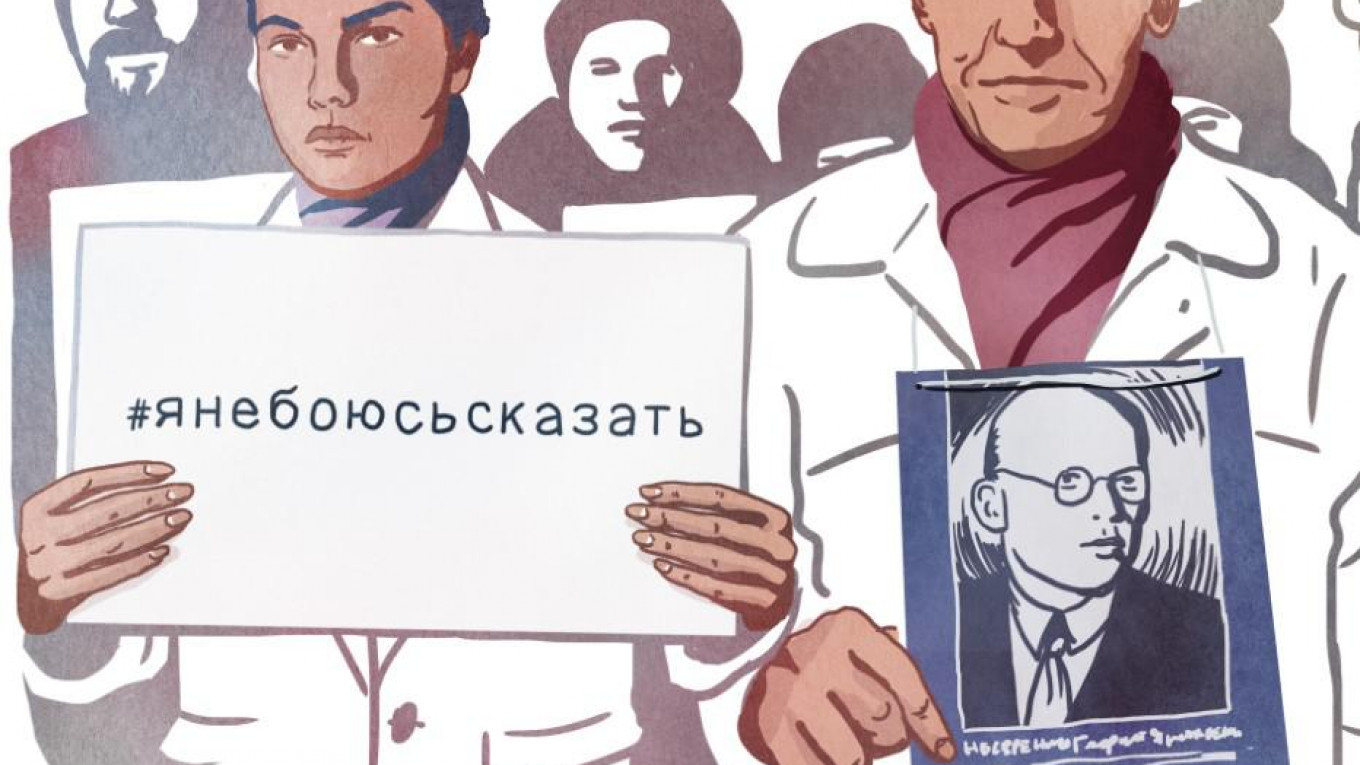

‘I Am Not Afraid to Speak’

On July 5, Ukrainian social activist Anastasia Melnichenko wrote a Facebook post that would become one of the most discussed of the year.

“I want us — women — to speak today,” Melnichenko wrote. “We do not have to make excuses. We are not to blame. Blame always lies with the rapist.”

Melnichenko encouraged women across the post-Soviet space to share their experiences of sexual harassment, and to post them under the hashtags #янебоюсьсказати, in Ukrainian, and its Russian version #янебоюсьсказать (#iamnotaftraidtospeak). Within hours, Facebook and Vkontakte — the most popular social networks in Russia — had been flooded with harrowing anecdotes of rape, assault and molestation. Thousands of women across Ukraine, Russia and Belarus had followed Melnichenko’s call.

“#IAmNotAfraidToSay that one day I went with my dad to visit friends at their dacha, a decent and beautiful family. The father of my dad’s friend lived there,” wrote one Facebook user, Anna. “I woke up early next morning, and he was lying next to me, drunk, with his hand in my underwear. I ran from the room and hid. I said nothing to my parents.”

Prominent Russian women joined the online campaign to tell their stories, hoping to change perceptions of sexual violence, with many arguing that society still finds the victim at fault.

“Anyone who says ‘women bring it on themselves by wearing short skirts’ should listen to my story,” the entrepreneur Alyona Vladimirskaya wrote on her Facebook page.

Vladimirskaya was seven months pregnant when a man assaulted her in the entrance hall of her building. “I didn’t think that I needed to be afraid of men in such a state,” she wrote.

The campaign was extremely important in changing Russian attitudes toward sexual violence, says Maria Mokhova, director at Syostry (Sisters), a center that works with rape victims. “We sometimes have a problem that people don’t believe us when we talk about the extent of such violence in Russia,” she says. “Anyone who read these stories could not fail to acknowledge, to visualize the problem.”

School No. 57

Russian Facebook users witnessed another outpouring of intimate secrets in the summer. This time, the confessions were from current and former students of the elite Moscow School No.57, who wrote that they had been sexually abused by their history teacher.

The social media storm was prompted by a post from Yekaterina Krongauz, a journalist at the Meduza news outlet. “For more than 16 years, we’ve known that the history teacher was having affairs with his students,” she wrote Aug. 29. “He was quite a handsome man: smart, ironic, charismatic. It was hard not to fall in love with him.”

Krongauz said that in these 16 years, she tried to break the story in the media twice, but failed. An amateur investigation conducted by former students of the school this year turned out to be more successful.

Olga Nikolayenko, a graduate of the school, spoke to almost a dozen people who claimed they had intimate relationships with the teacher in question, Boris Meyerson. The stories were hard to believe, she says, yet it was even harder to believe that people would invent them.

In late July, Nikolayenko went to the school director Sergei Mendelevich with the allegations. Initially, the director dismissed the allegations. Meyerson, who was in Israel at the time, quietly resigned. That might have been that, but a month later, Krongauz’s Facebook post unleashed a new series of confessions. Parents, current and former students, and some of the teachers were outraged by what they read.

The prestigious school’s management admitted to having serious problems, promised reforms, and even formed a council of parents and former students to supervise the reforms. A month later, a criminal case was launched against Meyerson.

Sociologist Ella Paneyakh believes that such grassroots activism in Russia will continue to grow. “The more it grows the more grounds there will be for political activism again,” she says. “When people participate in grassroots politics, they learn how it works and how to make this activism more effective. Russian society is learning all these things very quickly.”

Returning the Names

On Oct. 29, the eve of the Day of Remembrance of Victims of Political Repression, some 2,000 Russians gathered across the road from the headquarters of the Russian secret service, the successor to the dreaded Soviet KGB. After patiently waiting in line for hours, the individuals read out the names of those executed in Moscow during the darkest days of the Soviet Terror.

One by one, people read from the notes they had been given: name, profession, date of execution. They made improvised tributes. Sometimes, they added the names of their own relatives who had been executed. In all, 3,000 names were read out over 12 hours — from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m.

First organized in 2006 by the Memorial Human Rights Group, “Returning the Names” has turned into an annual event. The full list of those officially executed in Moscow stretches to 40,000 names. Almost half of them have been read out in the ten years the event has been held.

Every year, the ritual has attracted many Muscovites. But this year a record number turned out — even when the event fell on a weekday, under freezing October rain.

Activists explain the increased turnout as a response to moves within government to “rewrite” history and glorify aspect of Stalin’s rule. They point to the government’s increased dependence on victorious narratives from the Great Patriotic War (WWII) and Russia’s role in helping to defeat Nazi Germany.

Also lurking in the background was a government decision this year to declare Memorial a “foreign agent.” This label subjects the organization to increased bureaucratic scrutiny, and, ironically, has its linguistic roots in the Stalinist hunt for “foreign spies.”

“I think people were outraged and wanted to support us,” says Memorial’s Alexei Makarov, one of the organizers of the event. “But it is also a case of people taking part in a memorial event because there is much less room for real political protest.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.