2016 marks 99 years since “the most momentous train journey in history” according to Catherine Merridale, historian, author and former history professor at Queen Mary’s University in London. Her latest book, “Lenin on the Train,” documents the eight day train journey which would return Lenin from the obscurity of Swiss exile to Russian soil. It was a journey that would change the destiny of Europe.

Merridale, who also penned “Night of Stone,” “Ivan’s War” and “Red Fortress,” recreated the 2000-mile journey for the purpose of her book. She travelled through Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, Finland and Russia, leaving on April 9th from Zurich station — the same day Lenin embarked on his own historic journey. While Merridale traced the same geographic route, it was in very different circumstances to those Lenin found himself in.

Under pressure from the Austro-Hungarian empire for his political activities, Lenin sought refuge in neutral Switzerland, but when the February 1917 revolution occurred, he was determined to return to Russian soil. The journey across Europe to Petrograd — then St. Petersburg — has endured with the myth that it was in a non-stop sealed train, something which Catherine debunks. The reality was a little more mundane — Lenin and his cohorts took a standard Swiss train to the German border and before boarding a train east.

“This is where Lenin is committing an act of treason. He’s crossing the territory of an alien power in wartime,” said Merridale in an interview with The Moscow Times. “The deal which he struck via intermediaries in Switzerland was that the train should be treated as an extra-territorial entity. He was a lawyer, so he knew how to come up with euphonious phrases. And that meant no Russian on that train would get off and they would have no contact with the locals.”

Retracing History

Merridale followed the journey as accurately as possible and following exactly the same schedule. “What was really interesting was how many of the things were still so similar. Although obviously the trains are more comfortable,” said Merridale, who did allow herself to leave the train and stay overnight in hotels en route.

Lenin's train was comprised of a single carriage with five compartments for Russian use and space at the back for the luggage and the German guards, who were necessary since it would have difficult to cross wartime Germany without a local escort.

“But to prevent the Germans and Russians from having any contact, they drew a chalk line across the carriage floor. The Russians were not allowed to cross it and nor were the Germans. So, it’s slightly surreal already that the carriage was divided artificially into in Russian and German territory,” said Merridale.

“There were five compartments for the Russians — two second class and three third class. I can’t imagine how uncomfortable it was. Having to sleep every night in a packed compartment with your comrade’s feet in your face and the smell of their last lunch gently decomposing on the floor. Nobody had a bath, nobody got off and had a wash.”

With one bathroom between 34 people and Lenin forbidding anyone to smoke unless they were in the bathroom, the Communist revolutionary came up with an ingenious solution.

“Lenin intervened and issued passes. You could have a first class pass if you needed to use the bathroom for your normal biological reasons and a second class one if you wanted to smoke. You imagine the bickering and the discussions and the long debates about whether smoking is more important than peeing. But that is how that train was.”

Catherine speculates that part of the respect Lenin garnered was because of patience and excellent listening skills, something overlooked in much literature about him. “If he thought you had something to tell him that was important to the cause, he would listen very carefully. A lot of workers — ordinary workers — remember being surprised by how attentive he was,” said Merridale.

The Real Lenin

As she journeyed east, Merridale remarked not only on how the seasons seemed to “unravel backwards,” with sub-zero temperatures by time she reached Tornio, but also by how much the landscape of Europe has changed since 1917. It was Berlin that she first saw echoes of the remaining traces of Cold War divisions.

“In East Berlin the buildings are still Soviet-Style. West Berlin is still visibly a different city. But even that is beginning to vanish,” said Merridale. “The traces of the real past begin to vanish remarkably quickly There was a hotel in Malmo, where Lenin had been at (the Savoy) and I asked the Russian concierge — she was from Moscow — that I know you’ve got a plaque here for Lenin. And she said: ‘Lennon? You mean John Lennon?’”

Merridale feels that the Lenin we are offered today is a cultural construct, the product of the collapse of the Soviet Union and a sort of Post-Leninism.

“So, therefore, the point of the journey is to find the real one, the Lenin who was angry, who was daring, and who was willing to cross Europe against all the odds. Who was willing to even take the risk of being hanged because he was so hungry to lead the revolution.”

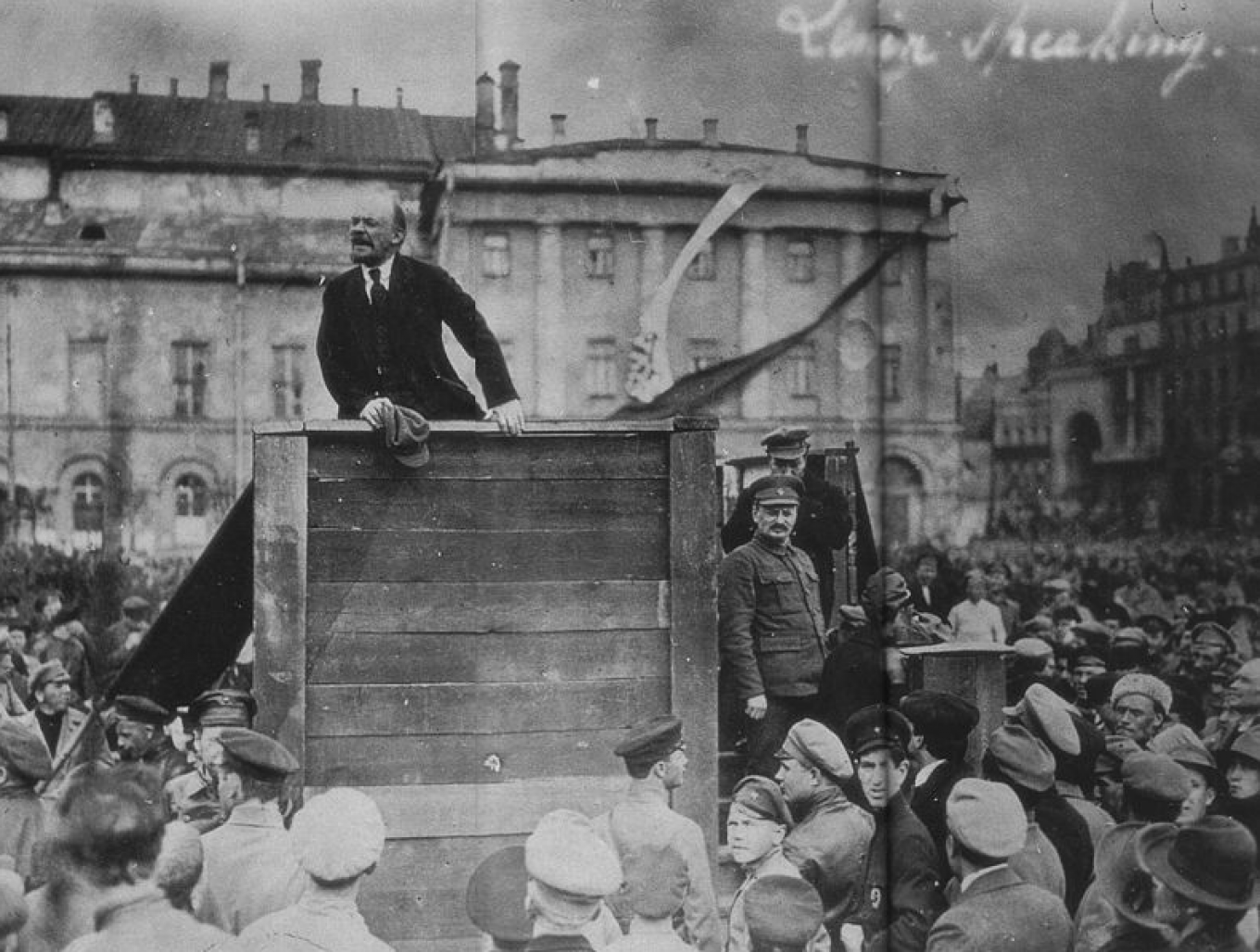

Lenin didn’t rest on disembarking the train in Petrograd. Instead from the very station platform he began to make speeches.

“What Lenin was saying was ‘No support for the provisional government,'” said Merridale. “No support for the War — we must come right out of the War immediately. Forget German aggression, our interests lie in pursuing the path of the Soviet. And that was heresy and political suicide, except it was Lenin saying it and he was able to persuade the party over the next few weeks to take that line.”

“Lenin on the Train” uses a quote from the revolutionary which seems as apt for 2016 as it did for 1917: “There are decades when nothing happens; and there are weeks when decades happen.”

“There are times when history accelerates,” said Merridale. “What it’s really saying is that things are changing all the time — social, economic, cultural. Undercurrents are changing, pressures are building up, which people don’t recognize and people don’t want to recognize. And some point they come to the surface and cannot be resisted.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.