Judging by the euphoria that gripped Russia in the wake of Donald Trump's unexpected victory, one might be forgiven for thinking it had somehow played a decisive hand in his electoral victory.

Few nations appeared as happy about Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential elections. When it was announced in the early hours of Nov. 9 in Moscow, ordinary Russians were abuzz with enthusiasm for the President-elect.

A Moscow fast-food joint offered Trump-themed burgers. A taxi driver in the city of Omsk advertised free rides. Captains of the propaganda industry thanked the American people for making “the right choice.” The floor of the State Duma erupted with applause.

“Such enthusiasm wasn't seen after September's State Duma elections,” says Valeria Kasamara, the head of the Laboratory for Political Studies at Moscow's Higher School of Economics. “Everyone had a position in these elections. Unlike our elections, no one was indifferent.”

National Scapegoat

From the mid-2000s, a very strong undercurrent of anti-Americanism has permeated Russian society. But it reached unprecedented heights following Russia’s March 2014 annexation of Crimea, the war in eastern Ukraine, and the subsequent isolation of Russia by the West.

According to every Russian pollster, a majority of Russians harbor anti-American feelings. They see the U.S. as their enemy, a nation intent on encroaching on Russia’s territorial sovereignty and pressuring others into taking a hardline approach to Russia. The notion that Madeleine Albright wanted to steal Siberia may be an internet meme, but its a conspiracy given serious credence by the Russian public.

This anti-American sentiment is very easy to exploit. “The Kremlin is keenly aware of Russian opinions and mentalities, and it builds its message on existing patterns, complexes and fears,” says Denis Volkov from Levada Center. “Yes, they shape it in a way, but it’s more that they leverage it and try to frame events in a way that they are most likely to accept it”.

Simply put, the average Russian “knows” who to blame for its hardships, and Putin consistently shepherds Russian public opinion in this direction. Most of the regime’s current legitimacy is built on the idea that Russia is a besieged fortress.

Deep, But Malleable Feelings

To what extent can we now expect Russian attitudes to change following Trump’s election?

According to Volkov, this will depend not only on what Trump’s actual policies toward Russia will be, but also “how the Russian media covers them.”

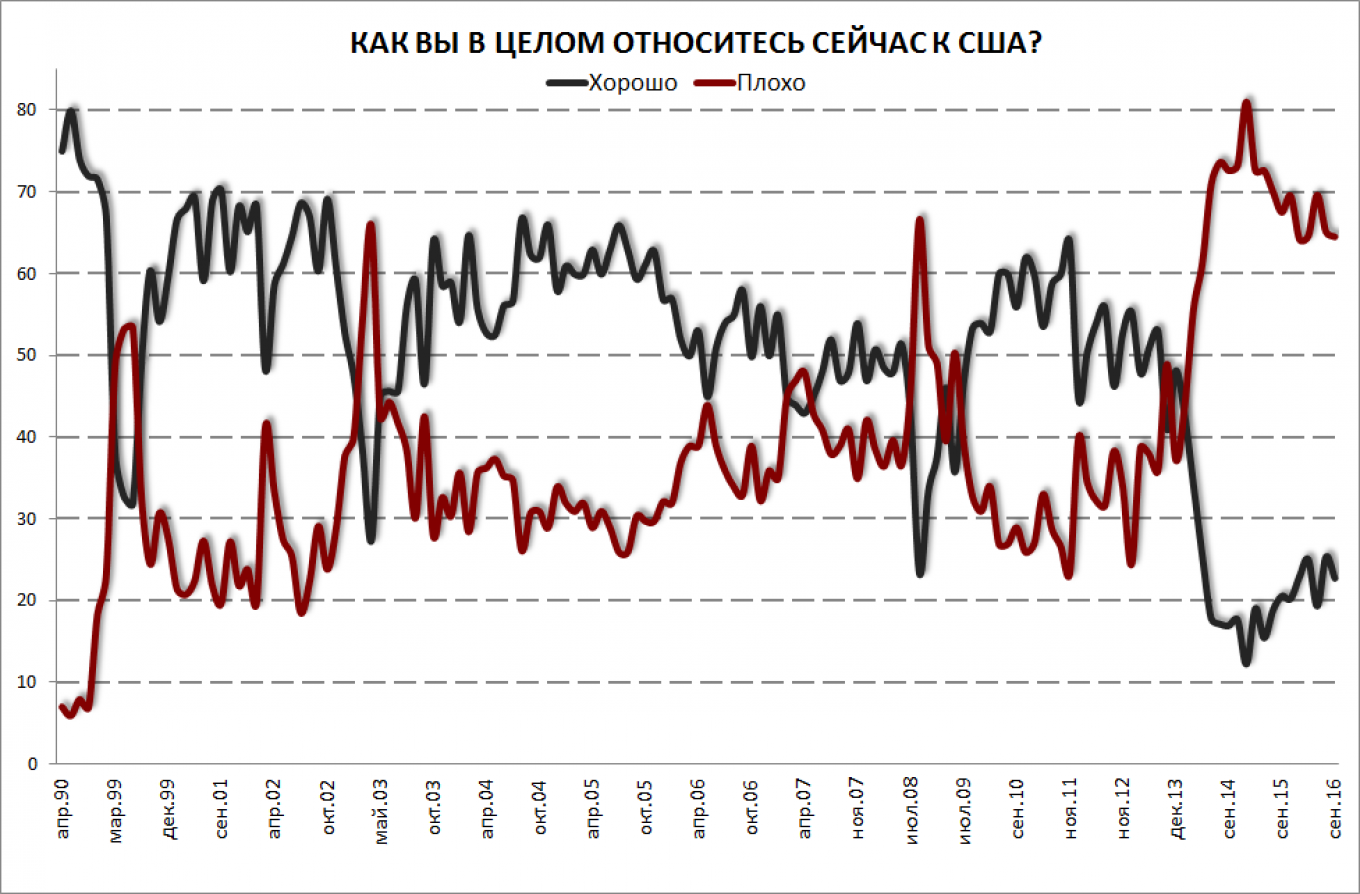

Although anti-Americanism in Russia runs deep, polling data over the years has shown it is also flexible and manageable. During the late 1980s, Perestroika and the fall of the Berlin Wall contributed to a dramatic reduction in negative feelings. These feelings then grew in the late 1990s — a reflection of NATO’s intervention in Kosovo — but dropped again in 2001, after Putin expressed his support for America after the 9/11 attacks. Anti-Americanism resurfaced in 2003 with the Iraq War, and then again in 2008 with the Georgian War, but settled around the early 2010s during President Barack Obama’s attempted reset in relations with Russia.

“Anti-Americanism is historically based on the idea that America is a foe of equal power,” says Alexei Levinson from Levada Center. “It’s an enemy which can turn into a friend quite smoothly. It’s anger, not aggression”.

The phenomenon of anti-Americanism was initially derived from the Russian nation’s inferiority complex, experts say. Psychologically, it can be understood as a means of routinely substituting a lack of trust in Russian authorities and institutions. It also stands in for self respect. According to Levinson, it transforms unacceptable political dissatisfaction over local politics into acceptable emotion about geopolitics.

And so, practically speaking, feelings can shift quickly. In Donald Trump, Russians have found a like-minded person to Vladimir Putin.

“The crucial point is this: Trump showed that he respects Russia’s power. For Kremlin strategists, this is a foundation upon which to build a domestic policy,” says Levinson.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.