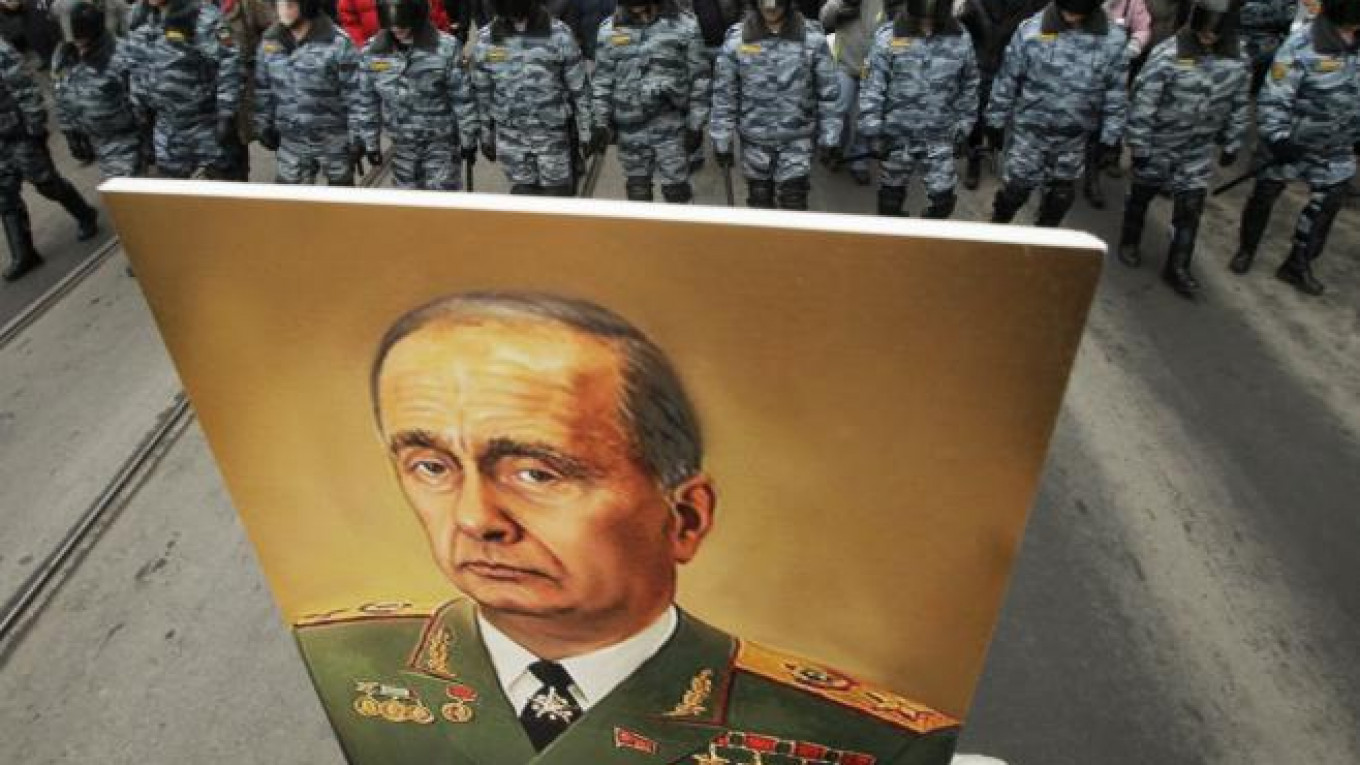

Just how long can President Vladimir Putin’s political system remain in place? On one hand, the destructive nature of the corrupt ruling authorities is too obvious for thinking people to hold out any hope of progress. On the other hand, the lack of mass protests after the Sept. 18 elections indicates the Russian authorities can do whatever they please. But for how long? Until the West applies new sanctions? Until the current crisis grows even worse? Until presidential elections in 2024? Until the Second Coming?

There are obvious differences between the current system and the late Soviet system constructed by former leader Leonid Brezhnev. But it is worth analyzing why the Soviet Union remained so stable despite being led by a tragicomic gerontocracy. There were, in fact, three main reasons for that stability.

First, economic problems in modern Russia have never been as bad as they were in Petrograd in February 1917, when the first, or February Revolution, took place. The Soviet people suffered from a very low standard of living, but those problems were never bad enough to prompt mass protests. People managed to get by with their meager lot and were unwilling to risk their freedom by engaging in a conflict with the KGB for the sake of mythical hopes of somehow improving their situation.

Second, the Soviet authorities constructed an effective system for suppressing dissent. The mechanism that former Soviet leader Yury Andropov introduced in the late 1960s was based on keeping “troublemakers” in check. The offending dissident would find himself invited to an interview with “the authorities” — meaning members of the security forces — where it was impressed on him that if he continued looking for trouble, he would undoubtedly find it. After such an encounter, the vast majority chose to keep their opposition-minded thoughts to themselves, while the occasional hero — unwilling to compromise with the regime — ended up in a labor camp or psychiatric hospital. This approach enabled the authorities to nip disobedience in the bud without having to create a cannibalistic system such as the Stalinist Gulag.

Third, the unity that the Soviet elite maintained — at least ostensibly, despite considerable infighting — played an important role. Nobody overthrew Brezhnev, even though he rarely regained consciousness during the last several years of his rule. All of the elder statesmen waited their turn — some even dying before that time came. Others were terminally ill by the time they ascended the “throne” and passed to the other world soon after. It was a quiet and steady process, and only a new generation of politicians — Gorbachev, Ligachev, Yakovlev, and others — managed to shake things up and introduce radical political changes.

Now Putin is repeating all three conditions of the Brezhnev-era stagnation. Russians’ standard of living has begun to decline steadily over the past two years, although there is no reason to expect it to fall drastically unless the price of oil plummets to $5-$10 per barrel. Just as people were willing to tighten their belts and wait under Brezhnev, Russians are even more willing to wait today, given the fact that they now live in a market economy and store shelves are stocked with a range of consumer goods. The old Andropov-era system of dealing with dissent is back in operation today. Anyone who challenges the authorities gets slapped with criminal charges.

Ordinary Russians have no one to tell them how miserable their lives are becoming. No new Gorbachev-like figure has appeared within the ruling elite. Then-President and now Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev tried to raise a Fronde of sorts, but Putin took him so firmly in hand that he now barely utters a peep about modernization. Those who rank lower than the president and prime minister have even less power to mount a serious protest. They moment they speak up, they are summarily dismissed. They cannot even get television airtime.

When the occasion demands, Putin has no qualms about firing his erstwhile friends such as former presidential chief of staff Sergei Ivanov or former Russian Railways head Vladimir Yakunin. Thus, despite its weaknesses, Putin’s system looks set to endure for many more years.

Dmitry Travin is a professor at the European University in St. Petersburg. He is the author of the book "Will Putin's System Survive Until 2042."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.