The result was the same—yet there is almost no fuss and no prospect of street protests. We could call the outcome of Russia’s parliamentary election last Sunday a continuation of the “Volodin Spring.”

The phrase was coined in honor of the Kremlin official who helped engineer the scenario of securing the desired results of a massive majority in the Duma for the ruling party, United Russia, but by gentler means than before. The Kremlin has thus avoided the furor it created last time, when large demonstrations greeted the results of Russia’s 2011 parliamentary elections.

The trick is that although the results mirror those of the past, the look of this election campaign was certainly different.

A first-time visitor to this autocratic state would have been surprised. There were fourteen parties on the ballot with different political agendas, many of which had been kept out of electoral politics for years, compared to just seven in the last elections. In central Moscow, Professor Andrei Zubov, who dared to compare Vladimir Putin’s takeover of Crimea to Hitler’s annexation of Sudetenland in 1938, ran for a seat against a protégé of exiled oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

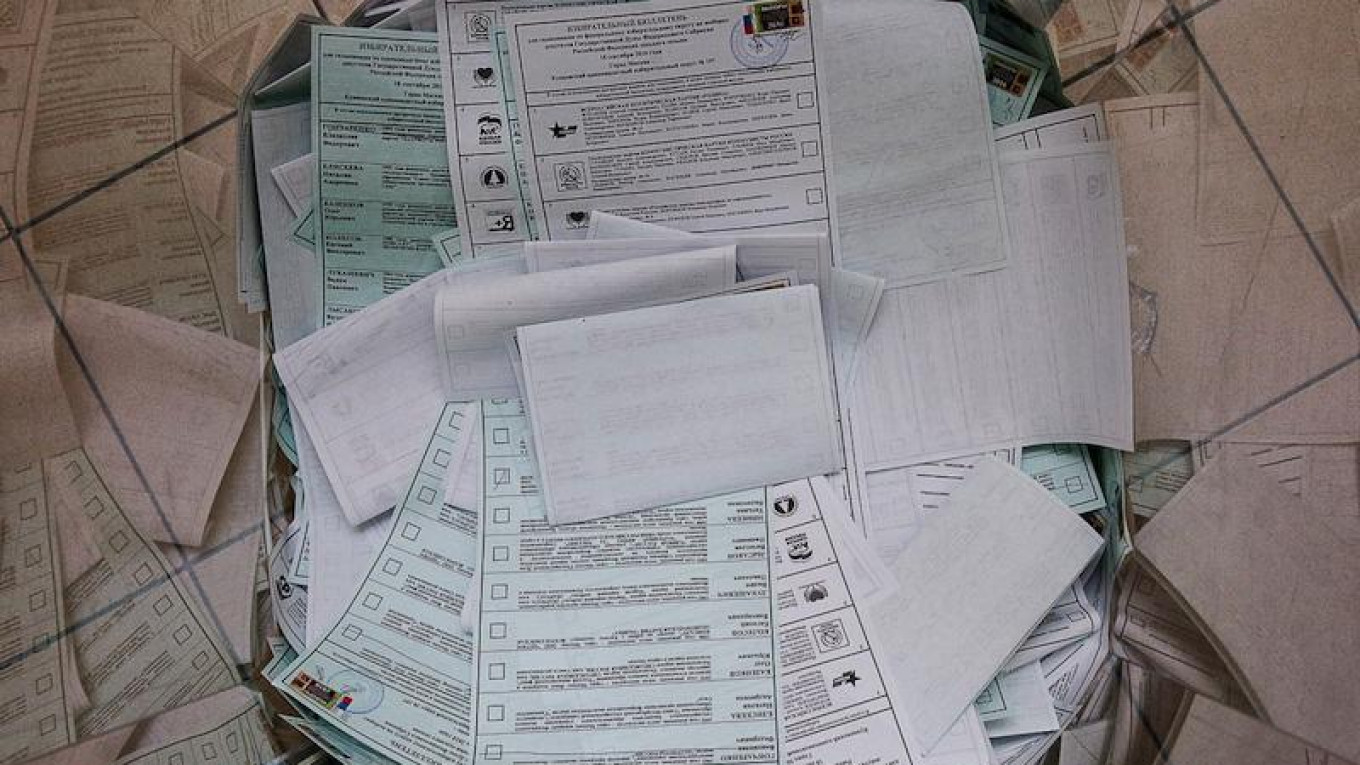

Meanwhile, the reputable Ella Pamfilova had replaced the notorious Vladimir Churov as head of the Central Election Commission. There were many reported irregularities. Incidents of ballot stuffing caught on video are available online. Suspicious throngs of workers, soldiers, sailors, and future pilots could also be seen at the polls. Yet even the toughest election monitors acknowledge that the vote looked better this time. The low turnout of 48 percent, as opposed to 60 percent in 2011, is also proof that there was less ballot stuffing and less of a demand from the Kremlin to deliver impressive results.

What has changed? Vladislav Surkov, the previous deputy head of the presidential administration, invented the concept of strictly managed “sovereign democracy” as a guiding principle for President Vladimir Putin’s early years in power. But the principle broke down in 2011 because it was too strict.

Enter Vyacheslav Volodin, who loosened things up by letting opposition anti-corruption campaigner Alexey Navalny, a leader of the 2011 protests, run for mayor of Moscow in 2013. He also permitted a greater polyphony of voices in parliament and on television—even though their polyphony was chiefly a matter of competing with one another as to who could combat Russia’s enemies most effectively.

Modern authoritarian regimes are more

sophisticated than their predecessors, being less prone to cults of

personality, to mass repression of opponents, and to formulas such as

“one people, one party, one newspaper.” Their parliaments are

elected to look at least somewhat respectable, not just packed with

candidates from one party elected by a 99 percent majority. Some

minimal degree of freedom exists in the media, public debate, the

judicial system, and freedom of migration.

This system is what Ozan Varol, an expert in constitutional law, refers to as “stealth authoritarianism.” It is a type of authoritarian government that has learned the rules of proper behavior. It prefers to consolidate its power by using legal mechanisms and democratic procedures rather than resorting to the old informal ways.

Why the masquerade? It is not a matter of trying to look good in international society. That would be the equivalent of trying to sneak into a grand party wearing a counterfeit Brioni tie. The first priority of any regime is to look legitimate in the eyes of its own people, and in the modern world new methods are required to secure that legitimacy. As the world becomes more global, so do the symbols of legitimacy.

Vladimir Putin and his protégés in government, parliament, and diplomatic service don’t stake their claim to power through birth or from having led a revolution. They depend on institutional legitimation, the assertion that they are genuinely popular with the people and the people have validated their power in a proper legal manner.

But this more flexible kind of system faces its own challenges and it is worth asking two questions. First of all, does authoritarianism completely discredit institutions or do ersatz institutions, like Russia’s Duma, contain the seeds of their own future transformation? Probably, both answers are true. But we should remember how easily in 1989 the Supreme Soviet of the USSR turned into a bona fide parliament, and how its one-party elections suddenly became genuine.

Secondly, is stealth authoritarianism just as authoritarian as its crude predecessor? Not quite. After all, if the regime’s main trick is to remain respectable within acceptable boundaries, it may need to expand those boundaries in order to adapt to new changes and stay alive. Stealth and disguise may prolong the life of an authoritarian regime, but they may also lead to an eventual transition to democracy.

To put it another way, the recent Duma elections, with their elements of freedom but predictable results, differ from classic Soviet totalitarian rule just as much as modern Russian propaganda differs from its Soviet predecessor.

In today’s Russia, the masters of spin don’t shy away from publicizing outside points of view, however critical or even hostile they might be.

Cynical as it is, this innovation is definitely an improvement on the old days. Nothing may change, but at least there is a chance that society eventually demands more, as it did in the 1980s. For the time being, however, we can only say that Russia has returned to where it was a hundred years ago: to being an autocratic monarchy with nascent institutions.

Alexander Baunov is a senior associate at the Carnegie Moscow Center and editor in chief of Carnegie.ru.

This article originally appeared on Carnegie Moscow's Russian Ideology blog

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.