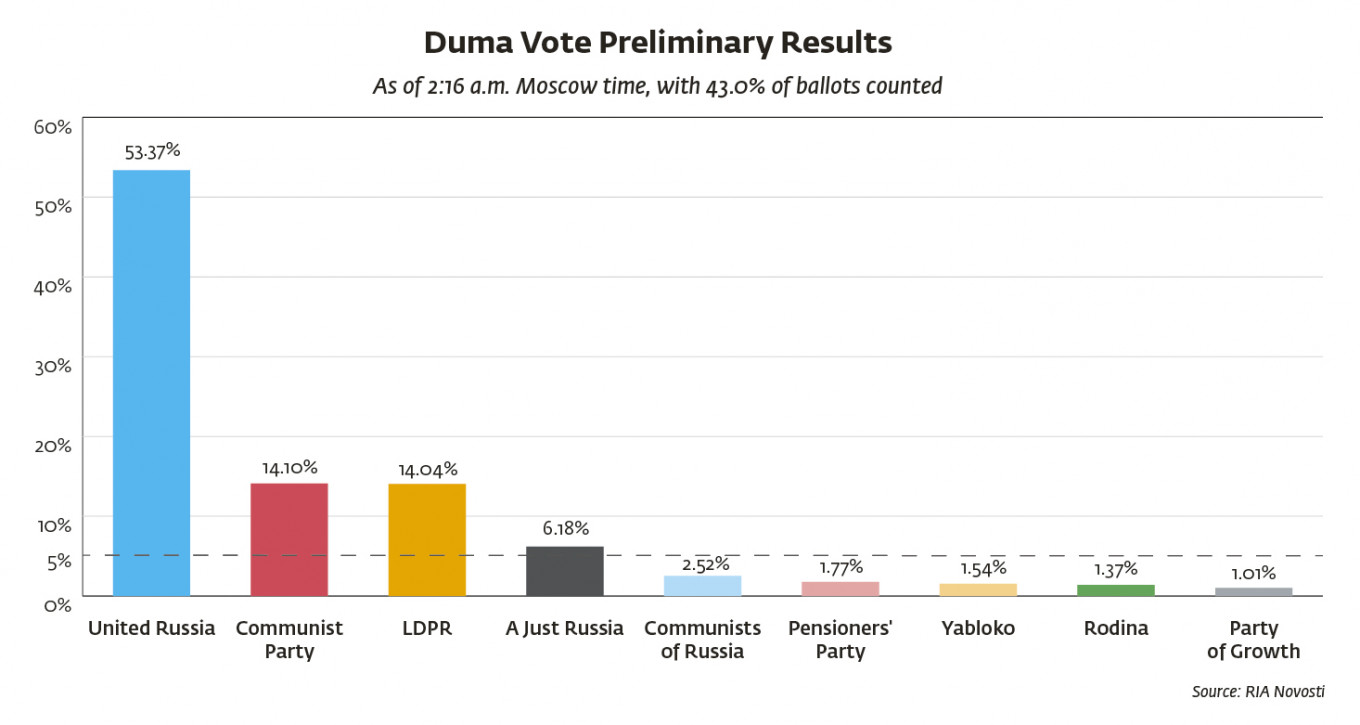

With over 40 percent of the ballots counted, the outcome of Russia's 2016 Parliamentary elections is completely clear: President Vladimir Putin came out on top of this election, with his party of power, United Russia, looking to take an overwhelming majority in the new State Duma assembly.

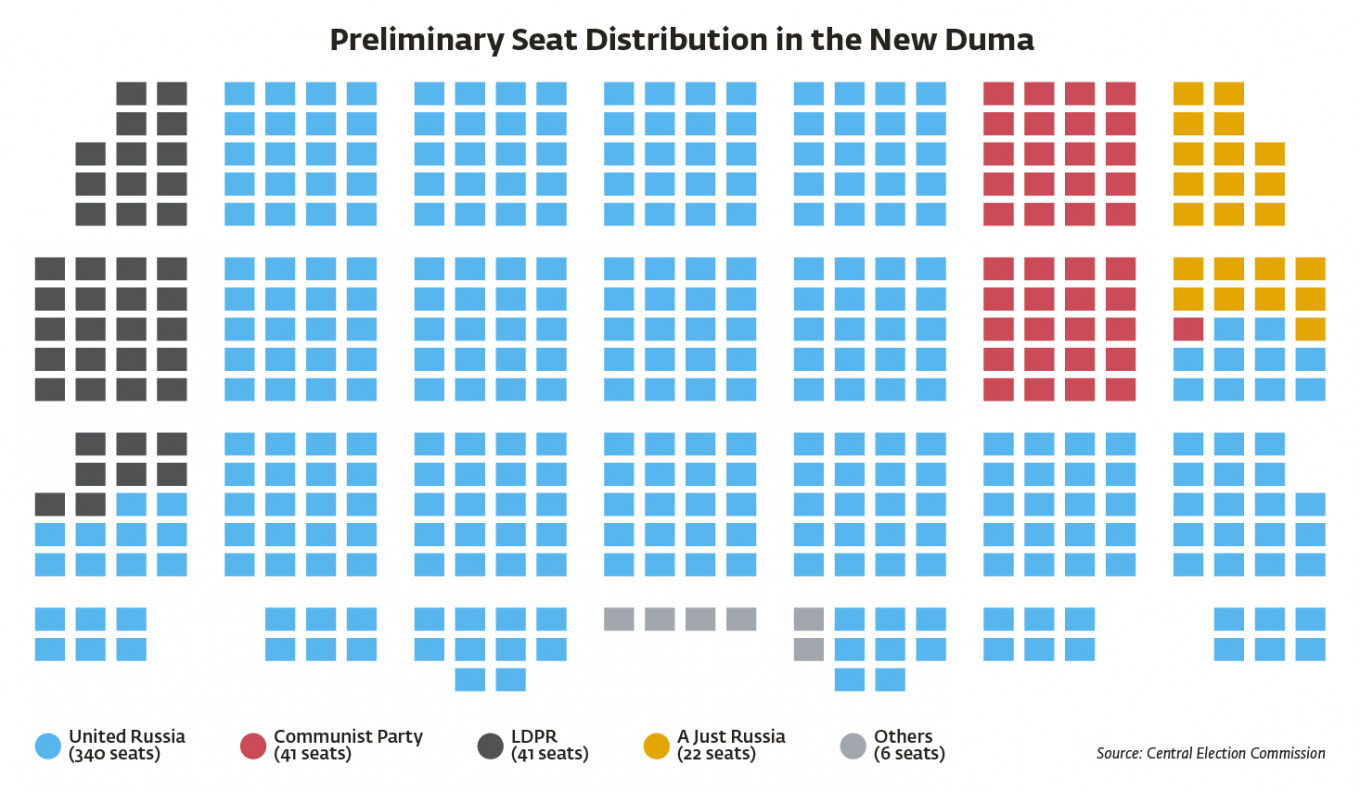

Half of the 450-seat State Duma is elected through party lists. United Russia has so far claimed 52 percent of that contest. Another 225 seats in the Duma are awarded in a single-constituency system, which means a district is represented by a single winner-takes-all candidate. When the dust settles, it is estimated that United Russia could walk away with far more than 300 seats.

A Crushing Victory

According to official results, the closest contest in the 2016 election was for second place. Russia's Liberal Democratic Party (LDPR), a nationalist outfit, has a very tight lead over the Communist Party for second place with 14.23 percent of the vote. The Communist Party has taken 14.19 percent. The party in fourth, A Just Russia, will enter parliament with around 6.3 percent of the vote.

LDPR, the Communist Party and A Just Russia are all known to be part of the so-called “systemic opposition,” a term denoting their official sanction by the regime. These parties are loyal to the Kremlin on all major political issues, such as the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the subsequent armed conflict in eastern Ukraine. Combined with United Russia, these four parties will take around 445 of the Duma's 450 seats. There is a huge doubt that there would be an independent voice to occupy at least one of the left 5 seats.

“It was not important for the Kremlin if United Russia ended up with 40, 50, or even 60 percent of the vote,” says Abbas Gallyamov, a political analyst.

But for the liberal opposition, the 2016 elections were a make-or-break moment, and the final tally was nothing short of a disaster for them. The traditional mainstream liberal party, Yabloko, failed to pass the necessary 5-percent threshold to win seats in the Duma. The other opposition party, PARNAS, led by former Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov, also failed to pass the mark.

PARNAS also failed to get a single deputy elected in the single-constituency districts, but in the hours after polls closed there is still hope that Yabloko can win a seat.

A Clean Campaign

The advent of the

single-constituency district contests were new to the 2016 election.

In 2011, all 450 deputies were elected through party lists, and in

this format United Russia barely won a simple majority of 226 seats.

The United Russia project was teetering on failure — something the Kremlin could not afford.

That election was not won cleanly. According to thousands of witness testimonies and independent analyses of electoral data, the 2011 election was severely rigged — possibly saving United Russia from failure in that election. But it came at a cost, the tampering sparked street protests in Moscow and other major cities. Known as the Bolotnaya movement, the rallies were the largest seen in Moscow since the 1990s.

Since 2011, the regime has introduced single-constituency districts. In the Kremlin's mind, this was a new safety mechanism. No matter what, United Russia would win a majority in this system.

“They were going to win it either way,” says Gallyamov. “At the same time, the Kremlin succeeded in persuading voters that this election would be honest and open. And this was a big victory.”

No major violations were spotted — though evidence of vote tampering was readily available — and there was no real need for rigging. Russian Central Election Commission chief Ella Pamfilova, who staked her career on a clean election, declared the 2016 election to be completely legitimate.

Shocking Turnout

This election was about voter turnout from the very start: The fewer voters turn out to the polls, the fewer votes cast for opposition parties and candidates. And in major urban centers like Moscow and St. Petersburg, voter turnout was the lowest seen in a decade. The overall turnout was around 40 percent of the national electorate — the lowest participation in a Russian parliamentary election in the country's post-Soviet history.

Five years ago, when Moscow became the center of a protest movement against a rigged election, voter turnout was about 50 percent. In Moscow on Sunday, just 30 percent of city residents turned up to vote. The situation was worse in St. Petersburg, where only 16 percent of the city's residents had voted by 5 p.m. In 2011, almost 40 percent had voted by 6 p.m.

In Russia, big cities feed opposition with votes and political force. But this time, they just abstained. “Think of it like a strike," says sociologist Ella Paneyakh.

And so, the Kremlin's bet on lower voter turnout proved to be the correct one, says Alexander Kynev, a political analyst. The low turnout was inevitable, first of all because the election was moved from December to early autumn. Second, because there were agreements between major parties not to touch sensitive issues in the lead up to the election.

“It was a rigged game,” Kynev says. For the electorate, it was simply dull.

Furthermore, the opposition parties didn't have the resources to campaign in the regions, Kynev says. “Their only chances were in the big cities and they blew it.”

“I want to say that I am sorry,” said Yabloko leader Lev Schlosberg on a TV RAIN talk show after the election. “We couldn't get through this iron curtain to our voters,” said Schlosberg, who is also editor-in chief-of the Pskovskaya Guberniya newspaper, which was the first outlet to report on Russian losses in the war with Ukraine.

“We failed to engage our voters in discussion. They don't believe in elections anymore, and they stayed home. This is our fault, and our responsibility.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.