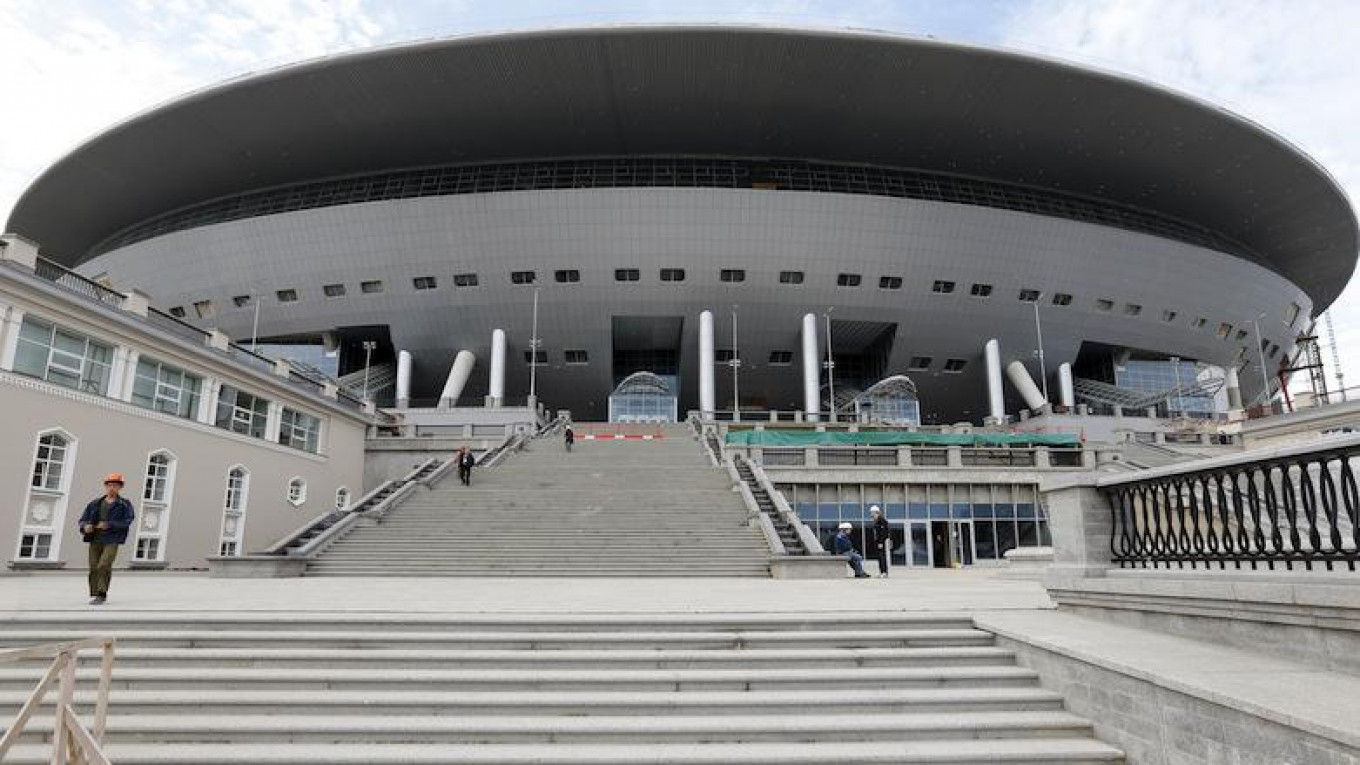

What St. Petersburg really needs are not schools and hospitals, but a new football stadium. Or such was the message sent to the city’s residents.

According to an order published on the administration’s website, some 505 million rubles ($7.8 million) reserved for the construction of six schools in St. Petersburg have been redirected into the city’s new Zenit Arena, the flagship site for Russia’s upcoming 2018 FIFA World Cup. Some 1 billion rubles, ($15.3 million) allocated to seven hospitals and clinics, were also siphoned off.

The outrage didn’t stop there. Already five times over budget, the stadium must be completed by December to qualify as a World Cup host, and requires extra cash if works are to be sped up. And so, the order, signed by St. Petersburg Governor Georgy Poltavchenko on Aug. 17, also diverted 313 million rubles ($4.8 million) from the construction of seven kindergarten schools, 140 million rubles from a sports facility for the disabled, and 150 million rubles ($2.3 million) from a community athletics center.

“The stadium, no matter what, needs to be finished,” famous Russian actor and St. Petersburg native Mikhail Boyarsky told the Sport-Express.ru website. “But schools, hospitals, and kindergartens also need to be built.”

The Kremlin has not, it seems, turned a blind eye to the problems plaguing the stadium and the decisions local authorities have made trying to fix it. On Aug. 31, the RBC news agency reported that Poltavchenko may be ousted following the September parliamentary elections as punishment for the project — which Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, as early as 2012, called “a disgrace.”

An Old Story

The project to build Zenit Arena began in 2007, before Russia even bid to host the 2018 World Cup, as a new stadium for St. Petersburg’s football club Zenit. It was supposed to be finished by the 2009 season, with a total estimated cost of 6.7 billion rubles ($102.7 million). But when Russia won the World Cup bid, international football governing body FIFA demanded design changes to meet World Cup standards.

So began a series of cost overruns, construction delays and corruption scandals. Subcontractors have been found to inflate cost estimates by millions of dollars, and a contractor was even sentenced to four years in jail for pilfering almost 150 million rubles ($2.3 million) in state funds.

In June, the project’s budget was increased by 4.3 billion rubles ($68 million). But the stadium’s primary contractor, Inzhtransstroi, asked for yet more money. The company claimed the city’s constant changes to the stadium design were disrupting work flow, and that the city owed them 1 billion rubles ($15.3 million) for already completed work. City authorities claimed to have given the company a 3.6 billion ruble ($55.2) advance for still uncompleted work.

In mid-July, Sports Minister Vitaly Mutko tried to intervene. “Why can’t they agree?” he told the R-Sport website. “If they are unable to agree, this situation will have to be resolved the hard way.”

The idea of missing FIFA’s December deadline was, Mutko said, “out of the question.”

Cost Cutting

The World Cup is rivaled only by the Olympic Games in terms of visibility and infrastructure investment. In advance of the World Cup, Russia promised to build 12 stadiums across 11 cities in western Russia — from Kaliningrad in the west to Yekaterinburg in the east; from St. Petersburg in the north to Sochi in the south. The initial budget was set at around 664 billion rubles ($22 billion at the time), a World Cup record, but still short of the $50 billion bill for Russia’s 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics.

Beset with controversy from the outset, Russia’s World Cup show was almost derailed last year. British newspapers detailed allegations that Moscow and FIFA had sealed an illicit agreement that Russia would host long before the organization’s official vote on various national bids.

With preparations already well under way, however, Russia managed to hold onto the games.

Now, the biggest threat to Russia’s hosting of the event are construction delays. Problems are mounting at several stadiums. In May, work was temporarily halted on a stadium in Samara over financial disputes between Russian authorities and the stadium contractor.

In the midst of economic crisis, the Kremlin is also cutting back on expenses. Taking into account the exchange rate and budget adjustments, the total dollar budget of the World Cup project now stands at less than half the original forecasts — a mere $9.7 billion.

Desperate Times, Desperate Measures

The Samara labor dispute was resolved by expanding the budget for that stadium by 900 million rubles ($14 million). But the situation in St. Petersburg, because of the looming deadline, is for the moment more serious. In the first of a series of increasingly desperate measures, city authorities in early August tore up their contract with Inzhtransstroi as the Zenit Arena primary contractor, and brought in another firm — Metrostroi.

But Metrostroi needed more money to overcome the deficit left by Inzhtransstroi’s 3.6 billion ruble advance. And so city authorities dipped into social works funding. As offensive as that may be to St. Petersburg residents, the contractor had an even more outrageous proposal to float at a press conference on Aug. 25.

“Don’t you remember how great it used to be [in the Soviet Union]? Toward the end of a project, we used to get the whole city involved: the students, anyone at all,” said Vadim Alexandrov, the company’s chief.

Not to be outdone, St. Petersburg Vice Governor Igor Albin reportedly asked a paratrooper colonel if his boys could be deployed to help with finishing Zenit Arena on time. The colonel allegedly replied, “just get me the commander-in-chief’s [Putin] order.”

Whether or not the order comes, the paratroopers don’t appear thrilled by the notion. An Aug. 25 press statement issued by their press office said simply: “Paratroopers have no time for construction work. Not even for stadiums.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.