Doug Hall’s ‘Moscow Metamorphosis’: 10 Years On

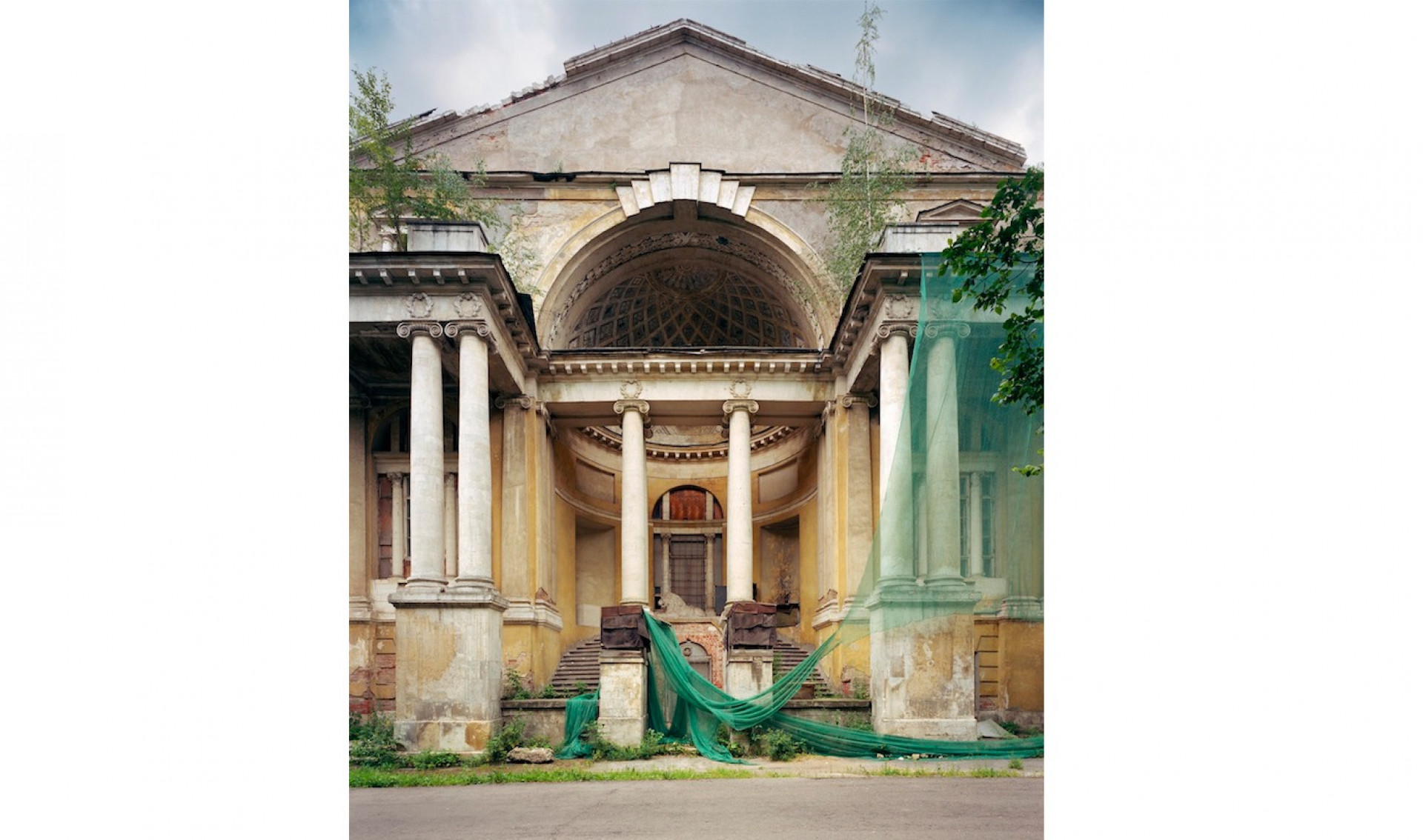

A decade ago, many of the people who formed the Moscow Architecture Preservation Society (MAPS) weren’t even thirty. The group was created to stop a construction boom unleashed on the city by Yuri Luzhkov, Moscow’s former mayor. The founders thought they could halt the whole thing if only they shouted to the world loudly enough that it was wrong to destroy the city’s architectural heritage.

The idea to found MAPS belongs to three people: Clementine Cecil, who worked in the Moscow office of The Times, Kevin O’Flynn, a reporter for The Moscow Times, and Guy Archer, an American publisher. I later joined as chairperson. The group soon established ties to existing organizations, like SAVE Europe’s Heritage and the World Monuments Fund. The latter introduced us to Doug Hall, who had never even been to Moscow.

Hall had become famous decades earlier, for radical video art, installations, and performances in the 1970s, and shifted to photography in the 80s. By the time he connected with MAPS, Hall was a professor emeritus at the San Francisco Art Institute. He was known for his cityscapes: large-format panoramas of major cities, capturing all their contradictory commotion and rigidity.

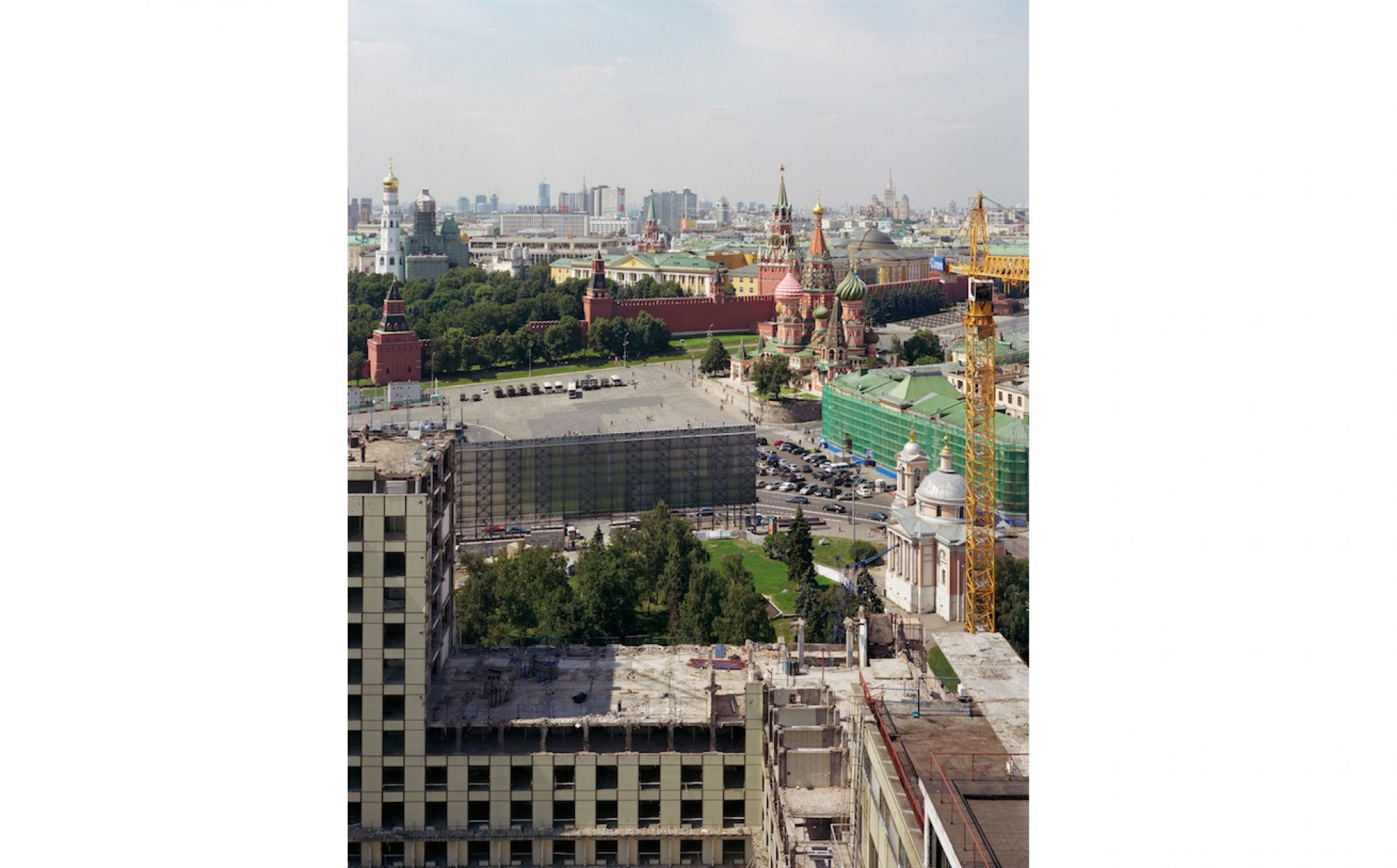

We both had something to offer each other: Hall wanted to capture another city in transition — the changing face of Russia’s capital — and we needed someone to document the rapid disappearance of historic Moscow. When it comes to permits, you can only guess how many administrative fiefdoms, both large and small, make up Moscow. Somehow, though, we got permission to film almost every building on our list, and in August 2006 Doug Hall landed in Moscow to begin his work.

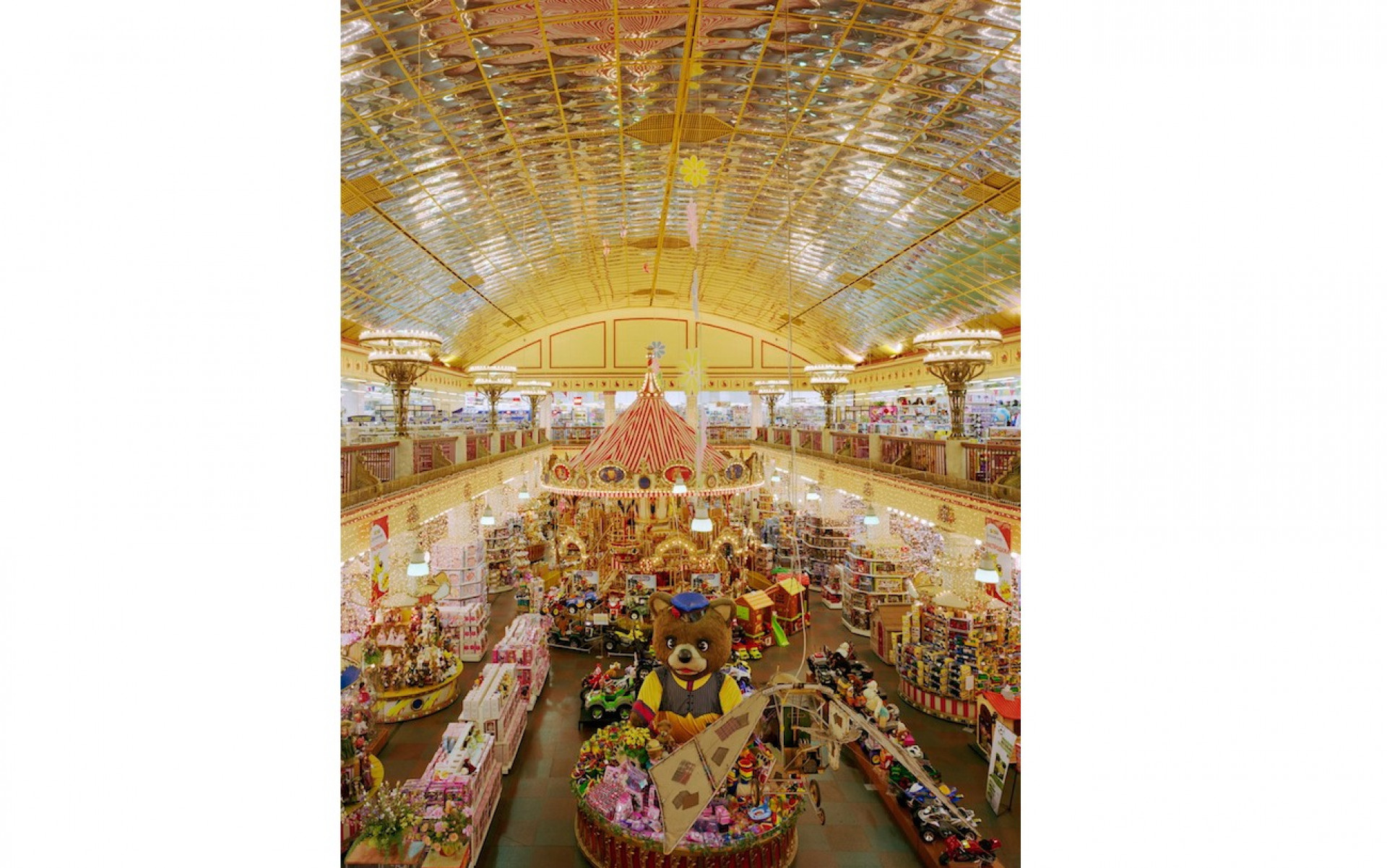

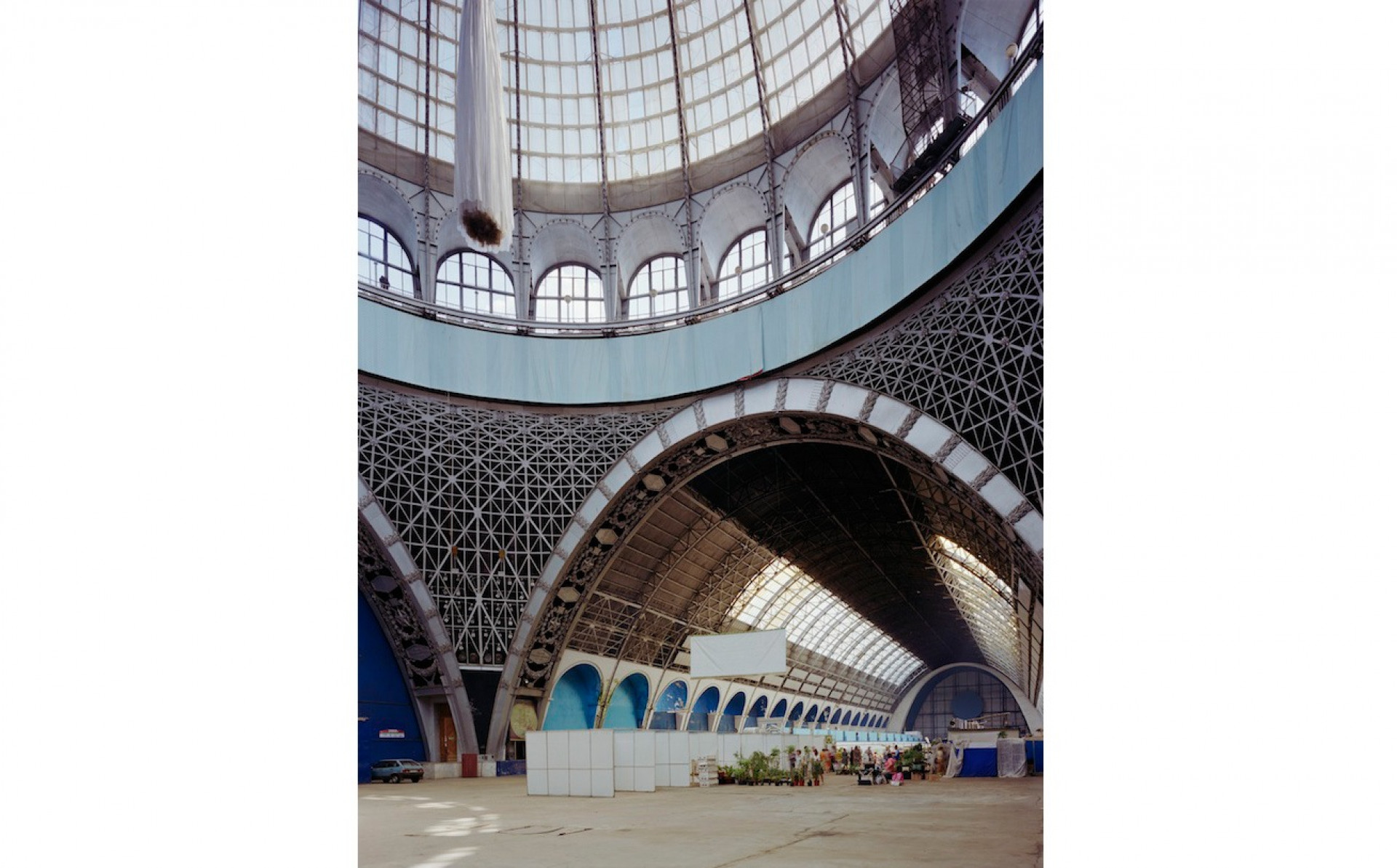

The project took our crew to some interesting places, to say the least. We went deep underground to film subway cars as they parked for the night. We climbed the Christ the Savior Cathedral and the towers of the Stalin skyscrapers, roamed the maze of Moscow’s courtyards, and wandered through vast residential areas, searching for the mood that would yield the perfect photograph.

Wherever we went, Doug and his large, old-fashioned camera and tripod drew looks from passersby. It was Doug’s point of view, though, that interested us: his perspective was unique and honed from studying dozens of world cities. What he chose to film was alternatingly unexpected and deliberately iconic.

The Yeltsin Fund made it possible for Doug Hall to work in Moscow for an entire month. When he was finished, Hall flew back to San Francisco with suitcases full of exposed plates and he spent the next few months sorting and retouching the slides. We hoped to stage exhibitions in Moscow, London, and New York, and had plans to publish a photo album with captions in Russian, English, and German. The book would have included a foreward by philosopher and Moscow aficionado Karl Schlögel.

In the end, however, we could only afford the album’s layout. We had no luck finding more sponsors, and the entire project was shelved in 2008, when the financial crisis hit. The project was only ever displayed once in public, over a single holiday weekend in 2009, on Pokrovsky Bulvar in Moscow.

It’s been ten years since Hall’s visit, and not everyone in the original crew still lives in Moscow. Even Luzhkov has gone, making way for Mayor Sergei Sobyanin, who continues the destruction of Moscow’s architectural treasures. Almost every building that Doug Hall photographed has changed since 2006: some were carefully restored, others were radically reconstructed, and several were smashed to the ground.

Ten years ago, we wanted to call the book “Moscow: Metamorphosis,” and the city has indeed changed vastly since then.

An exhibition of Doug Hall’s work will open this month at the Benrubi Gallery in New York. That project, “Letters in the Dark,” is based on correspondence between Franz Kafka and his translator, Milena Jesenská. The exhibition includes two videos depicting fragments of their letters, along with photos of buildings, doors, gardens, and rooms — including places where Kafka actually lived, as well as random places added to create a surrealistic impression of pre-war Prague. Hall recorded some of those images in Moscow.

Marina Khrustaleva is the former chairperson of the Moscow Architecture Preservation Society and the coordinator of the Arkhnadzor advocacy group.