Vladimir Zhirinovsky runs his hand over a CD of 50 songs composed by a fan in his honor. He is clearly pleased.

“All of humanity knows me,” he says. “My name is in encyclopedias, in registers and databases. Books have been written, films recorded. I’m happy, I’m satisfied.”

For better or worse, the boastful leader of Russia’s ultranationalist Liberal Democratic Party is right about one thing: With more than two decades at the helm of the first registered post-Soviet opposition party, Zhirinovsky is an institution of Russian political life.

Young Vladimir Putin was still at the bottom of the political ladder in St. Petersburg’s mayoral office when Zhirinovsky’s rabble-rousing rhetoric first burst onto television screens during presidential elections in 1991 (he came third).

With Zhirinovsky now 70 years old, it cannot go on forever. Pundits have predicted his imminent resignation for years. But on the eve of parliamentary elections on Sept. 18, he’s at it once more, lashing out against everyone and no one: foreign multinationals (“We don’t need them!), the wrong exports (“The best bread is being sent abroad!”) and the right ones (“We should increase production so that the West chokes on our products!”).

Behind the demagoguery, however, is a shrewd political strategist who knows his audience. Leaning back into his chair at the party’s parliamentary office overlooking the Bolshoi Theater, he has turned the volume down a few notches.

“We don’t want a revolution,” he says.

Growing Pains

Visitors to his office are warned by a sign on the door: “Attention. No hugs, kisses or handshakes.” Zhirinovsky is not one to take life lightly.

The future politician grew up in Kazakhstan’s Almaty, in a single-parent household — his father emigrated to Israel where he died in an accident, leaving the young Vladimir with little more than the Jewish patronymic, Volfovich. On her deathbed, his mother told him: “Volodya, there is nothing to remember, not one joyful day.”

“My mother had nothing. She worked in a canteen, her first husband [Zhirinovsky’s father] died, then there were more deaths or she was abandoned. There was absolutely nothing for her to be happy about,” says Zhirinovsky, with unusual softness. According to him, it ingrained in him a deep sense of compassion and understanding for the losers of the Soviet regime.

“They had a home, something to eat, clothes, but they weren’t happy, they had nothing to be proud of,” he says.

Restoring wounded pride was a prospect that appealed to millions of Russians after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Disillusioned with the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin, reverting to communism was no longer an option. Zhirinovsky’s LDPR provided a third way: While liberal reformers were praising the West as an example to follow, Zhirinovsky glorified Russia’s imperial past and threatened the Baltic nations with nuclear annihilation in mediagenic sound bites.

That communication style resonates with Zhirinovsky’s core electorate, says Alexei Grazhdankin, deputy director of independent pollster the Levada Center.

The LDPR appeals to “the marginalized voter from depressed regions,” he says — largely low-educated, middle-aged and living in Russia’s interior or smaller settlements. “These voters are not looking for long explanations or deliberations, they respond to light and sharp phrases,” he says.

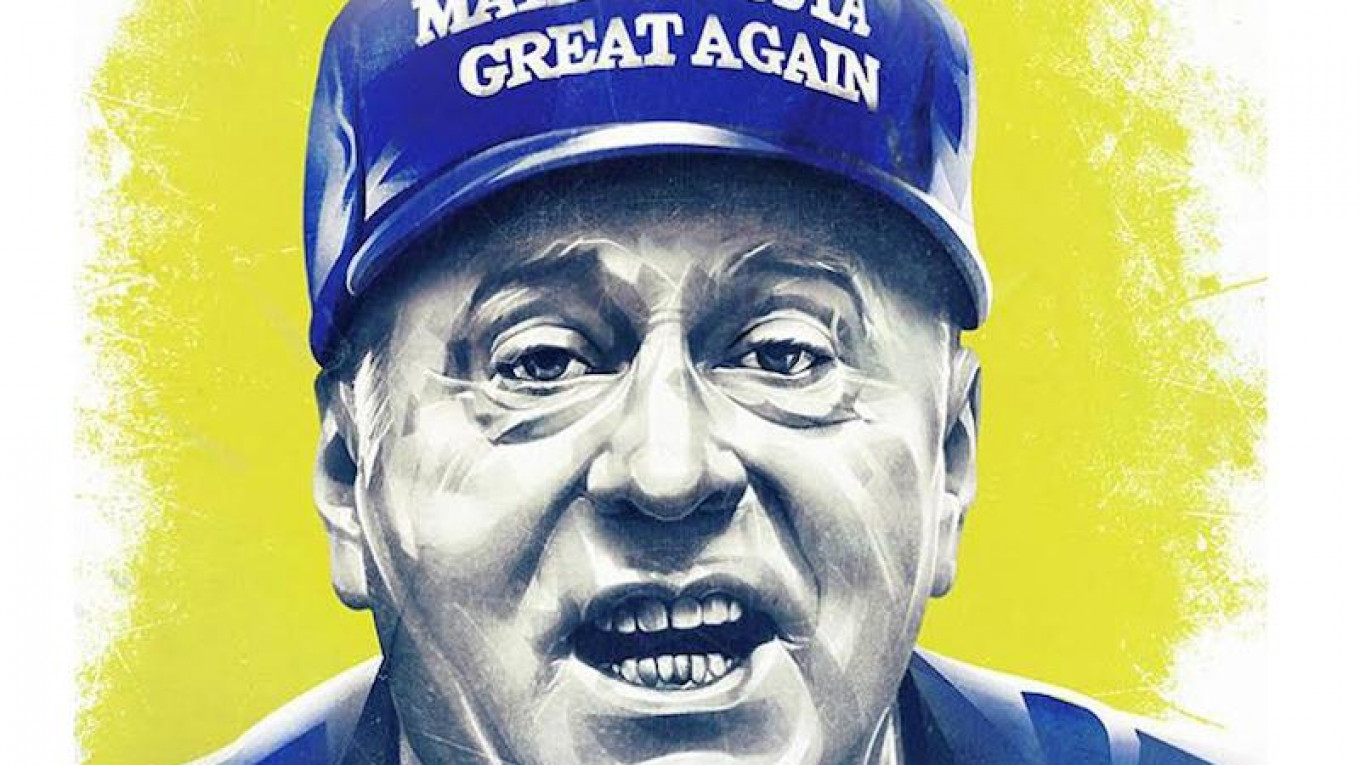

At home, Zhirinovsky’s brand of bizarre performance politics is unrivaled. Now, he’s found a kindred spirit in the country that is usually first on his hit list.

“I feel a certain sympathy toward Donald Trump, his manner, his position. He’s close to me in a way. He speaks freely and reacts instantly,” Zhirinovsky recently told a press conference. As if to prove their shared over-the-top-manner, he claimed he had sent a sample to a U.S. lab to test for possible familial ties with the Republican presidential candidate.

Even without common genes, the two share a talent for grabbing headlines — Zhirinovsky is also a frequent name in the foreign media, who alternate between depicting him as a political buffoon and a guinea pig used by the Kremlin to gage the electoral pH with radical proposals.

The LDPR leader finds the attention from foreign media flattering. “Of course I like that I’m famous there [in the West]. It’s a plus,” he says. But he insists that his media success is his own doing, dismissing professional speechwriters. “I’d sooner tear their texts apart than look at them,” he says.

Pragmatism

Zhirinovsky’s direct talk and promises of Russia’s revival as a great power proved a huge success. During the LDPR’s first parliamentary election in 1993, they won 23 percent of the vote. The liberal establishment was caught completely off guard by what it saw as the fledgling democracy’s swerve towards ultranationalism, bordering on fascism. “Russia, you’ve lost your mind!” the prominent literary critic Yury Karyakin famously said.

For the LDPR, however, things went downhill from there. After its initial success, the party has never garnered more than 12 percent of votes.

Zhirinovsky has his own explanation as to why.

“They started marking us down,” he said. “The results were already being fixed during Yeltsin’s time — the elections in 1995, 1999. We left behind the Soviet system but failed to create a new, competitive democracy.”

It is a deadpan acknowledgement of widespread vote rigging. But despite the opposition talk and unsalted criticism of government officials, the LDPR has consistently backed the Kremlin on all major issues, most significantly in the early 2000s when Putin’s Kremlin needed support from smaller parties in parliament.

Conformism seems to be in the party’s DNA. In an interview with journalist Vladimir Pozner in 2010, Zhirinovsky said he believed it was the LDPR’s “moderateness” that convinced the Communist authorities to register it as a party in the first place.

“The LDPR doesn’t act against the country, we don’t say: something’s wrong with this country,” says Zhirinovsky. “We say: Our country has problems. Whereas they [the liberal opposition] want an ‘orange revolution.’”

Behind his self-proclaimed “flexible approach” appears to be pure pragmatism. “Democrats in Russia have three paths open to them: the grave, emigration or prison,” he told journalist Ksenia Sobchak matter-of-factly during a recent interview.

The fourth path, according to the LDPR, is realism and patience. Lots of it.

Zhirinovsky’s nightmare scenarios are the uprising of 1917 and the Soviet Union’s collapse, both “revolutions” with disastrous effects, he says. “We destroyed everything too briskly, too harshly,” he says.

“There is no ideal system just as there are no ideal persons, ideal families or ideal cities, we have to get away from ideals.”

The upcoming parliamentary elections will be “better” than those in 2011, predicts Zhirinovsky, adding he doesn’t expect any “major” vote rigging.

Russia’s ruling party, United Russia, has a real rating of 25 percent, according to Zhirinovsky, who predicts they will bring it up to 40 percent in the final vote. “But that’s already better than 70,” he concludes.

‘Second Choice’

For his own party, Zhirinovsky sees a result of 22 to 25 percent. Polls are less sanguine, putting the LDPR at 10 to 15 percent several weeks before the election. But, unlike other parliamentary opposition parties, the Communist Party and A Just Russia, the LDPR stands a good chance of increasing its number of Duma seats, currently at 56 out of 450.

After Western sanctions imposed on Russia over its role in the Ukraine crisis and annexation of Crimea, Zhirinovsky’s once outlandish statements about the existence of a foreign threat no longer seem so outlandish to many Russians.

“To many voters he now looks like a more serious politician who for years spoke the truth,” says Alexander Pozhalov, research director at the Moscow-based Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Research.

The LDPR stands a good chance of ousting the Communist Party as the so-called “second-choice party” for undecided voters. With patriotism and anti-Western rhetoric having become government policy in recent years, the LDPR is a viable alternative for those who support Putin generally, but are unhappy about socio-economic conditions. “It’s a safe vote,” says Pozhalov.

An economic crisis caused by low oil prices and Western sanctions is also playing into their hands.

“Their old slogan: “We’re for the poor! We’re for Russians!” is still applicable today,” says Konstantin Kostin, a former Kremlin aide who is now head of the Civil Society Development Foundation.

The biggest threat to the party is Vladimir Zhirinovsky himself. Though still active on the campaign trail, the veteran politician cannot hide his age. The slightly overweight belly has grown, and his eyes are narrow slits above pale, puffy cheeks. In debates, he looks to take increasingly greater effort to wind himself up.

For Zhirinovsky, retirement is unlikely to be the end of his political career. He’s already been promised a Kremlin-appointed seat as senator in the Federation Council. But for his party, it could spell the end.

“The Communists may still get people voting for their ideas, but, with the LDPR, it’s mostly about Zhirinovsky himself,” says Levada’s Grazhdankin.

Zhirinovsky’s more measured son Igor Lebedev, deputy chairman of the LDPR’s faction in the Duma, would seem his most likely successor.

But his father suggests that option is off the table. “The moment someone appears who’s better than me, or at least someone who will be as good, that person will get a chance,” he says.

Undoubtedly, in Zhirinovsky’s eyes, those shoes will be difficult to fill.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.