Russian real estate developer Alexander Senatorov began buying apartments in Moscow’s Narkomfin building in 2006 as a gift for his fiancée, Alexandrina Markvo, who was fascinated by the revolutionary constructivist style it epitomizes. He pledged to restore its former glory.

Having had almost no maintenance since it was put up in the 1920s, Narkomfin was disintegrating. Water ran down its walls and chunks of masonry would occasionally fall off.

“[The Senatorov era] began with a love story,” says Marina Khrustaleva, an expert on constructivism who has closely tracked the history of the building.

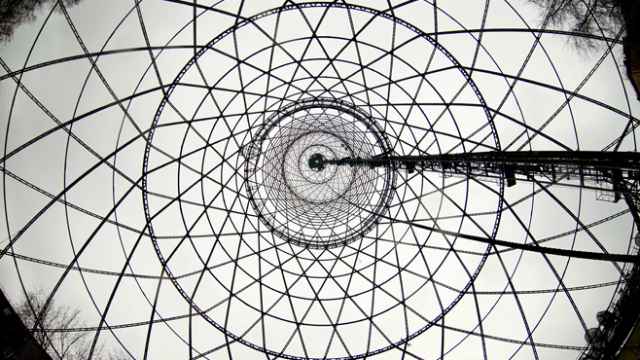

Nestled between a small park and the U.S. Embassy in central Moscow, Narkomfin’s radical use of color, light and space makes it one of the country’s most striking buildings. Envisaged as the prototype for a new way of communal living, it was built at a time when the communist ideals of the 1920s had yet to give way to the pomp of Stalinism. Narkomfin's global influence was immense during a century that saw the mass construction of modernist apartment blocks.

Many hoped Senatorov’s love story would prove a turning point, but it quickly crumbled. His marriage fell apart after three years and his fortunes were badly affected by the 2008 economic crisis. Narkomfin remained in a critical condition and many began to doubt a genuine restoration would ever be possible.

“There is a general absence of understanding that the short period of avant-garde culture in the 1920s and 1930s was Russia’s most significant contribution to modern architecture,” says architect Alexei Ginzburg, the grandson of the celebrated constructivist pioneer, Moisei Ginzburg, who designed Narkomfin.

Mysterious New Owners

After years of decay, however, change now appears imminent for Narkomfin.

Senatorov told Russia’s Kommersant newspaper Aug. 1 that Kopernik, his investment company, no longer controlled the building. Two days later, the Moscow city government announced the winner of an auction of part of Narkomfin was an outfit called Liga Prava.

The director of Liga Prava is Garegin Barsumyan, an Abkhaz-born lawyer with a background in banking and legal dispute resolution. He has little public profile.

During an interview with The Moscow Times in Narkomfin last week Barsumyan says that as well as the being the director of Liga Prava, he is also its “de jure” owner. But he says other investors — both individuals and financial institutions — are also involved. He declined to identify them, or reveal how many there are. “I don’t want to go into the details,” he says.

One person currently working on the plans for Narkomfin described Barsumyan as a “representative” of the owners. Another of his acquaintances says it was unlikely he had only invested his own money: “It seems there is someone behind him” they say.

Senatorov Out?

Senatorov confirmed in written comments to The Moscow Times that he sold his stake in Narkomfin last year. “I took a decision to get rid of all my real estate assets. About two years ago,” Senatorov says. He declines to comment on to whom he sold Narkomfin, on his relationship with Barsumyan, or Barsumyan’s employment history.

But the three years Barsumyan spent working for Kopernik, where he headed the company’s legal department, and the presence of unnamed investors in the project have prompted speculation Senatorov remains involved. Senatorov even retains an office in Narkomfin.

Russian business daily Vedomosti cited Aug. 4 a former partner at Kopernik saying Barsumyan was a frontman for Senatorov.

Senatorov flatly denies he has any financial stake in Narkomfin. And a friend of Senatorov’s told The Moscow Times the developer “will be really glad to be rid of it [Narkomfin].”

Barsumyan also rejects suggestions of Senatorov’s involvement — but he says Senatorov would be welcome to re-join the project. “Senatorov exited in 2015,” Barsumyan says, “[But] maybe he will still return. We are open to investors. To old partners and new.”

Follow the Money

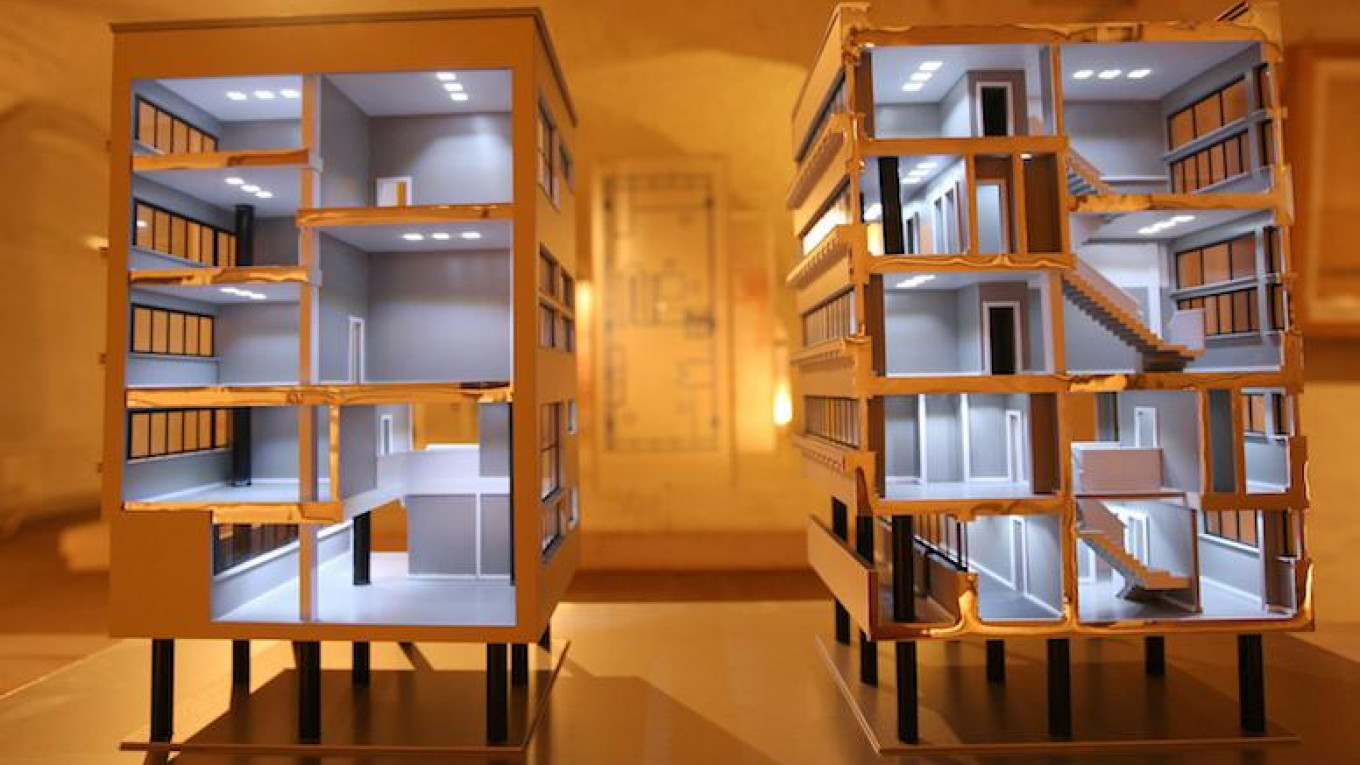

Narkomfin has about 4,000 square meters of floor space and Liga Prava now controls everything except for about 200 square meters, which are held by private owners. Almost all of the apartments are currently in use — either as offices, workshops or living space.

Both Senatorov and Barsumyan decline to reveal how much Senatorov received for his stake. But Liga Prava beat off two bidders to pay 101.4 million rubles ($1.6 million) to the Moscow city government this month for about 1,600 square meters of the site including the building’s ground floor and the so-called communal bloc. At the same price, Senatorov’s stake would have been worth about $2 million.

Previous owners have wrestled with how to make a re-development of the building profitable. The task of renovating constructivist buildings, often built using poor quality materials, is not straightforward.

And there is no easy way to transform Narkomfin into the luxurious apartments beloved by Moscow developers. After all, who needs tiny apartments with no kitchen? Senatorov’s plan to market Narkomfin to rich Muscovites looking for a pied–à–terre was never realized.

Senatorov told Kommersant newspaper in 2014 it would cost $12 million to completely renovate Narkomfin. In the end, he made little mark on the building apart from consolidating ownership of the apartments and installing a yoga center on the roof.

Barsumyan declines to reveal how much Liga Prava will commit to the planned restoration, but says he is determined to make money. “It’s not simple. But what is simple in life?” he asks. More financing needs to be raised to fund the restoration process, according to Barsumyan.

Ginzburg’s Return

One of Liga Prava’s first moves on acquiring a controlling stake in Narkomfin was to employ architect Alexei Ginzburg, whose family’s history is wrapped up with that of the building itself. Ginzburg’s grandfather, Moisei Ginzburg, was one of Russia’s leading constructivist architects and built Narkomfin. His father, Vladimir Ginzburg, was heavily involved in efforts to research and preserve the building.

Ginzburg says he was first taken to visit Narkomfin when just five or six years old.

“There can’t be anyone else apart from Ginzburg in this project,” says Khrustaleva, who is also a member of the Moscow-based architectural preservation organization Arkhnadzor.

Senatorov originally worked with Ginzburg on restoration plans, but the two men fell out, and Senatorov proceeded to authorize some limited building work.

Ginzburg says he was shocked when he saw the changes. “Before we had the historical surfaces but now almost all of them are covered by paint, plaster or ceramic tiles and the original windows have been switched for plastic ones,” says Ginzburg. “What was done in the last few years has become a serious problem for today’s restoration work.”

Back to Basics

Built for employees of the Commissariat of Finance, Narkomfin was an attempt to realize a new form of living space for the fledgling Soviet state. While residents had their own two-floor apartments, they shared kitchens, washing space and even a kindergarten.

Each of the 45 duplex apartments has a bedroom facing east, so residents wake up to the rising sun, and a living area facing west to take advantage of the evening light.

Ginzburg says there are enough extant plans and research to recreate the exact form of the original building, including the striking color code (doors to the apartments are painted alternatively black and white), which was influenced by Germany’s Bauhaus movement.

When Liga Prava took control of Narkomfin, they did not re-hire the Kleinewelt Architekten bureau that Senatorov used latterly. Barsumyan says he disagreed with many of Senatorov’s ideas, including proposals to build an underground swimming pool or turn it into a hotel.

“Nothing will change from what was conceived in the original architectural plans,” says Barsumyan, who adds the building will be transformed into “business class accommodation.”

Clearing work in the communal bloc purchased from the Moscow city government earlier this month is already under way.

Liga Prava’s plans envisage the removal of the ground floor and the return of pillars that once made the building appear as if it was floating. Ginzburg says that, once renovated, the communal bloc, which is connected to the main corpus by an elevated walkway, will contain a café and may be opened to the public.

Against the Grain

Building work could begin as early as October, according to Ginzburg. But Barsumyan says this is conditional on additional investment and not likely to start before the end of the year.

Any successful restoration of Narkomfin will take place despite widespread official indifference to the fate of constructivist buildings in Moscow — an attitude that echoes the disapproval leveled at the constructivist movement in the 1930s. Under Stalin, constructivism was vilified as cosmopolitan, bourgeois and unsuitable for Soviet workers.

Deputy Moscow mayor Marat Khrusnullin provoked the ire of preservationists in June when asked about constructivism. “I personally believe these buildings should be left as monuments of how not to build,” he responded.

A 1920s housing estate in the central Moscow Khamovniki district was torn down earlier this year and developers recently demolished the constructivist Taganskaya telephone station despite well-attended street demonstrations calling for it to be saved.

Russia’s constructivist buildings are usually protected by the lesser powers of regional authorities — as opposed to more comprehensive federal oversight. Many of them are falling down and preservationists insist renovation is urgent otherwise they will be lost forever.

“All foreign architects ask to go and see Narkomfin: their education begins with descriptions of this building in their textbooks,” says Khrustaleva. “It is of fundamental significance for the architecture of the 20th century.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.