“The market is a manifestation of life. The brightest manifestations of life occur in its condensation: in certain points, certain lines, certain spatial-temporal formations.”

For some, this might seem to be just a bunch of random words. In reality, they are the introductory remarks of an academic article supposedly penned by Anton Vaino, President Vladimir Putin’s newly appointed chief of staff.

Full of complicated terms, schemes and graphs, the article describes a device called a “nooscope.” Designed in Russia five years ago, the nooscope studies “the collective conscience of mankind” and registers “among other things, the unseen.” A network of “spatial scanners,” monitors changes in the “biosphere”.

“There is no way to prove that the world we’re used to — the world we know through sight, hearing and touch — exists in reality and not only in our imagination,” concludes the article, which was published in 2012 by the economic journal Issues of Economy and Law.

Anton Vaino today occupies one of the top positions in Russia’s bureaucratic hierarchy. His rise was as meteoric as it was unexpected, after Putin astounded Kremlin watchers by replacing close ally and political veteran Sergei Ivanov with someone younger and less well-known.

What we do know about Vaino, 44, is that he is the grandson of the former head of the Estonian Communist Party. Fluent in English and Japanese, he trained as a diplomat before serving in Russia’s embassy in Tokyo in the late 1990s, and then at Russia’s Foreign Ministry. Since 2003, Vaino has risen up through the presidential administration — forging a career as chief of the presidential protocol department, where he was in charge of schedules and similar management issues.

Russia’s officials describe Vaino as an efficient and loyal bureaucrat and Putin’s personal choice as his chief of staff. According to unnamed sources cited by business daily Vedomosti, Vaino is a “brilliant administrator.” One source referred to an “affable personality” and claimed the Kremlin’s new man had a reputation for living modestly, which would certainly be unusual in the field of top government administration.

Getting a Degree

It is not unusual for Russian officials to dabble in academic activities — getting a degree has been a mandatory ritual for a long time ago. Putin, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and dozens of government ministers set the trend, and lower-level officials follow. For some, obtaining a degree is a necessary condition of climbing the career ladder, says Sergei Parkhomenko, co-founder of Dissernet, an online group fighting intellectual fraud. “For example, if you’re a district prosecutor and want to become a city prosecutor, you need to get a Doctorate. It’s not a written rule, but that’s how it works,” Parkhomenko told The Moscow Times.

According to Kommersant newspaper, Vaino published several articles on the economy in Issues of Economy and Law when he was the head of government staff between December 2011 and May 2012. In 2013, Vaino reportedly received an economic degree, about the equivalent of a U.S. masters, after writing and defending a dissertation on the mineral resources industry. Articles in scientific journals, including the one quoted above, were, apparently, a stepping stone to the dissertation. In Russia, anyone seeking to obtain such a degree needs to have articles published in such journals.

Vaino’s career, however, did not depend on getting a degree, argues Parkhomenko. Instead, to officials like him it is a matter of prestige. “It is like having a certain car, wearing a suit of certain brand, living in a mansion in a certain place, owning real estate abroad and such. It is part of a ’success kit’ for these people,” the activist says.

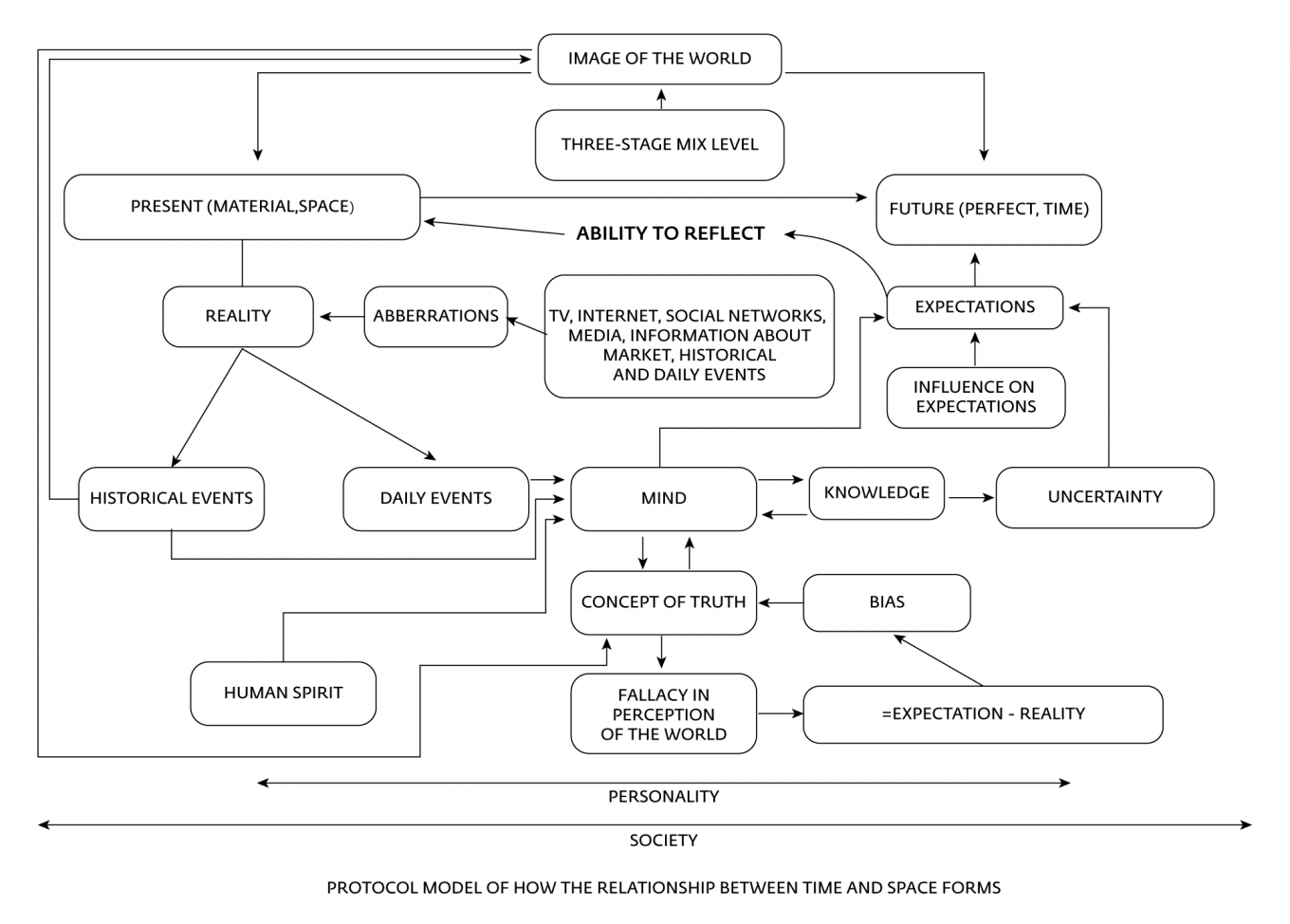

One of the graphs from the article about "nooscope" that is supposed to be about economy.

'Aboriginal Science'

Often, officials don’t write dissertations themselves but plagiarize the work of others. Dissernet is particularly active in fighting intellectual fraud in scientific papers. They usually target plagiarism. In this case, the mere choice of the subject for an article sparked media storm.

The piece about “nooscope” — whoever did in fact write it — has nothing to do with science, says Kirill Martynov, a philosophy professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. “It is not even clear to which area of expertise we can attribute it. Basically, it’s nonsense. In terms of Russian language, the words in it make sense, but in terms of science — they don’t,” Martynov told The Moscow Times.

The article lacks many of the formal characteristics of a piece of scientific work, like coherence, logic and the facts being attributed to sources. “Instead, the article uses semi-mystical terms and facts that cannot be verified or proved,” the philosophy professor says. “For example, it says that ’nooscope’ has 50 patents, but there is no attribution to any of them.”

This falls into a trend called “aboriginal science,” according to Martynov. “In aboriginal science people imitate scientific activity, using platforms that have nothing to do with international science, but are convenient for achieving their goals,” he says.

The article is far from being scientific, agrees Alexander Etkind, a renowned culture historian. At the same time, resembles a Utopia as a genre. “There is hope in the article that new will change the quality of government. The new device, developed under mythical protocols and patents, is supposed to control things that can’t be controlled: Internet, market, life,” Etkind told The Moscow Times.

Earlier on Monday BBC Russia reached out to one of Vaino’s co-authors, Viktor Sarayev, and asked about the “nooscope.”

The response was elliptic. “[Isaac] Newton invented the telescope, [Antonie van] Leeuwenhoek invented the microscope, and we invented the nooscope — a device of the material Internet that scans transactions between people, things and money,” Sarayev wrote back to the BBC. He declined to give more details about the device.

The bigger question is whether Anton Vaino, president’s chief of staff, really wrote it, says Mikhail Gelfand, a prominent biologist and co-founder of Dissernet.

“If he is really behind this delirium, then it’s quite scary,” Gelfand told The Moscow Times. “If, he’s just signed off on other people’s work, we have another problem. That means we’re living in a country where head of the presidential administration can sign off on an absurdity with his eyes closed”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.