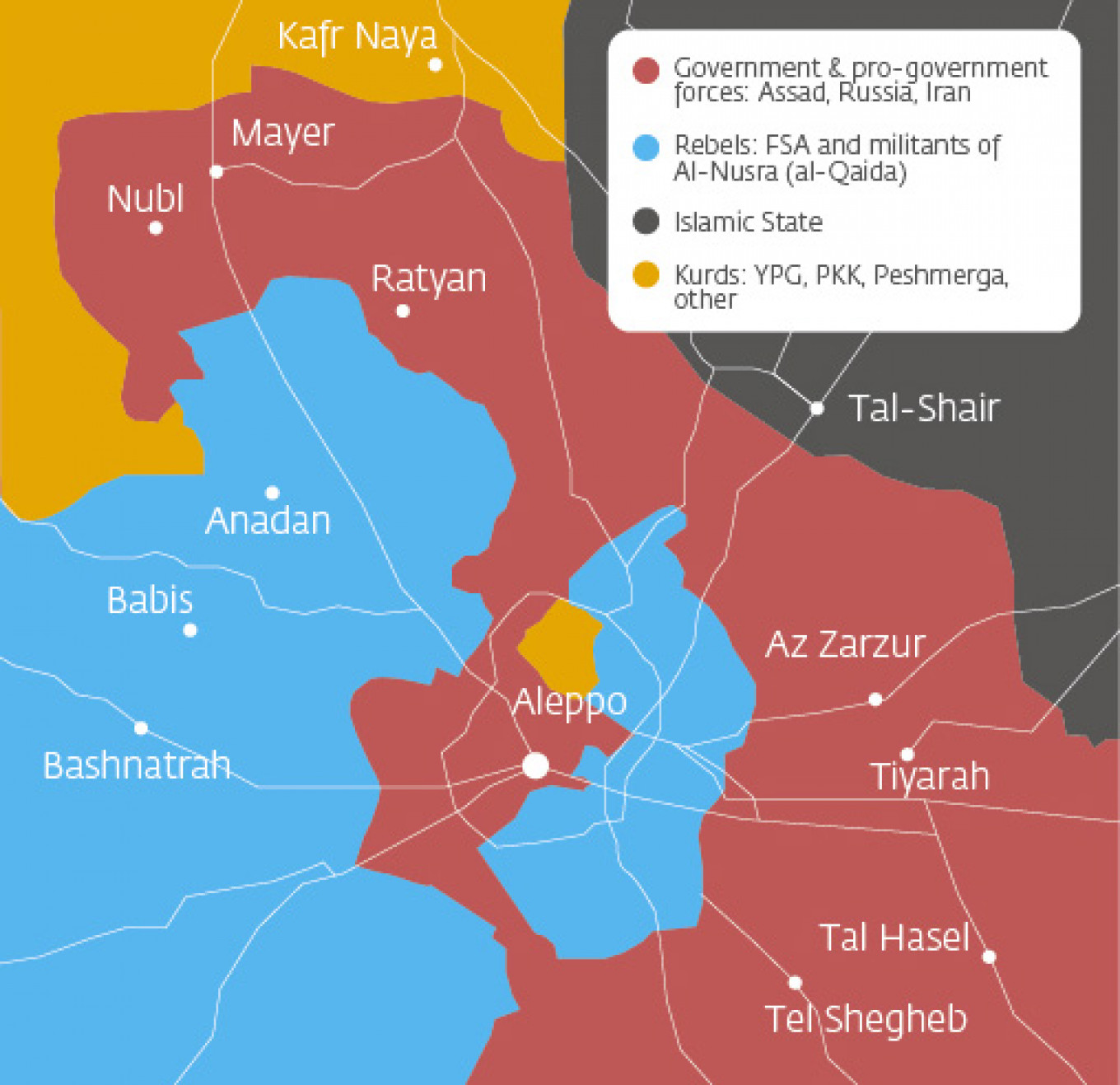

The final offensive began on June 25. After more than two years of fighting to retake the opposition stronghold of Aleppo, once Syria’s largest city, troops loyal to Syrian President Bashar Assad stood ready to encircle their forces in the city’s east. The objective was Castello Road, the last remaining supply line connecting Syrian opposition forces in Aleppo to their allies outside the city.

The siege operation can, in fact, be traced back to October 2015, shortly after Russian President Vladimir Putin deployed air support to Assad’s embattled regime. Those military operations focused on retaking territory to the south and east of Aleppo, and cutting opposition forces off from reinforcements via the M5 highway, which veers toward rebel territory to the southwest.

In February, concurrent to attempts by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry to negotiate a cease-fire in Syria, pro-government forces began to fight for control of territory north of Aleppo. The process has drawn out over the course of the year, as both sides engaged in pitched battles for the north, especially the vital Castello Road, through which opposition forces received supplies and reinforcements.

Only by June 25 did regime troops find themselves in a position to finish their encirclement of the city. On July 7, backed by Russian air power and Syrian Kurds within Aleppo, the Syrian army was within one kilometer of Castello Road. By July 17, they had overtaken the highway, and began tightening their grip around the rebel position. On July 27, regime forces declared all supply lines had been cut.

After more than five years of war, east Aleppo is still home to some 300,000 people. When government forces took Castello Road, these civilians found themselves trapped in one of the most frightening situations imaginable. Cut off from supplies, the Aleppo civilian population depends on the mercy of Syrian President Bashar Assad and his Russian backers.

On July 28, the citizens of Aleppo appeared to have been offered respite. Speaking in a televised address, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced that Russia and Assad's regime would open three “humanitarian corridors” for civilians and “fighters who want to lay down their arms.”

But, hardened by civil war, the remaining residents of Aleppo have little faith in their opponent's sincerity.

Breakout or Siege

Few within east Aleppo believe the government and its allies are coming to help. Civilians in Aleppo are collecting tires and burning them in the streets to create dense smoke they believe might protect them from air strikes. Meanwhile, the opposition is fighting to reestablish a supply corridor in the southwest of the city.

On July 31, militants from Jabhat Fatah al Sham — formerly the al-Qaida affiliated Nusra Front — alongside the Free Syrian Army and Islamist group Ahrar al Sham launched an offensive driving northeast toward the opposition holdout. On Aug. 1, the force claimed to have made modest progress toward their goal.

To link up with trapped opposition forces, however, this group needs to take one of Assad's largest artillery bases, and cross 2.5 kilometers of enemy-held territory. This is no easy task.

If the breakout attempts fail, some anticipate the Syrian and Russian militaries will attempt to bomb the opposition areas into submission. With supplies waning, the residents of Aleppo may truly have only one way out: the Russian and Syrian humanitarian exit corridors. Thus far, according to Hadeel Al-Salchi of Human Rights Watch, the corridors have remained empty.

“Those on the ground say the mood in Aleppo is that no one wants to cross,” says Al-Salchi. “They fear it is just a plot to change the demographics in Aleppo,” she says.

Others wonder if the Russian-Syrian humanitarian corridor is a scheme to legitimize the eventual leveling of Aleppo, by claiming all who stayed are combatants. This, after all, is a tactic Russia employed in Grozny during the Second Chechen War of 1999-2000.

Some activists in Aleppo have reported that regime snipers are currently targeting the safe corridors and shooting at those attempting to escape. The information was considered unverified by both Human Rights Watch and the Syrian-American Medical Society.

“There is a lot of confusion about what is going to happen with these corridors,” Al-Salchi says. “If people want to stay in Aleppo, they have a right to stay. You can't just flatten it with air strikes, assuming everyone who remained is a combatant.”

Russia has denied it its planning an offensive on the city. Indeed, Russian Middle East expert Yury Barmin doubts this is Russia’s primary intent. “Russia is preparing the ground to retake Aleppo if necessary, but Aleppo is more valuable to Russia encircled but not captured, a perfect bargaining chip in talks with the U.S. over Syria’s future,” he says. “Then again, Assad clearly wants to retake the city and this may be a source of conflict between Moscow and Damascus.”

Supply Concerns

Access for international aid organizations and medical professionals within eastern Aleppo remains highly problematic. One of the only groups working still operating there is the Syrian-American Medical Society (SAMS). According to representative Dr. Majed Mohamed Katoub, the group are keeping a minimum of 35 doctors inside eastern Aleppo, to provide what he calls “basic service.”

Katoub warns supplies will be quickly exhausted in the event of a siege. The most important resource is fuel, which is used to run crucial siege infrastructure such as bakeries and hospitals. “The bakeries will run out of fuel in just a few weeks, and the hospitals can hold out for a bit longer, perhaps three to four months,” he says. “We initially estimated six months.”

This may turn out to be an ambitious estimate. When asked if SAMS believed it was being intentionally targeted by Syrian and Russian forces, Katoub answered affirmatively. “Attacks on our hospitals have been systematic,” he says. According to the doctor, shelling across the city intensified in July, and casualties treated in SAMS clinics increased by at least 30 percent over June.

“People can live with the bombing, but they cannot live without health care services,” he says. “We know this is why they are attacking hospitals, because people will be forced to flee.”

For those who remain inside eastern Aleppo, there are no good options — the prospect of living under siege or a hazardous journey into an unknown future in enemy territory. Many fear the latter more than the former, with tales of torture or execution doing the rounds within the city.

“We have been trying to collect information on patients who need urgent medical evacuation from Aleppo,” says Katoub. “But all of them — the patients and the doctors — said if the UN is not involved in the corridors, that they would prefer to die in Aleppo. If Putin and Assad really want to help, they need to bring treatment into the city, instead of asking them to flee.”

* Jabhat Fatah al Sham, al-Qaida, Ahrar al Sham, Nusra Front and the Islamic State are all terrorist organizations banned in Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.