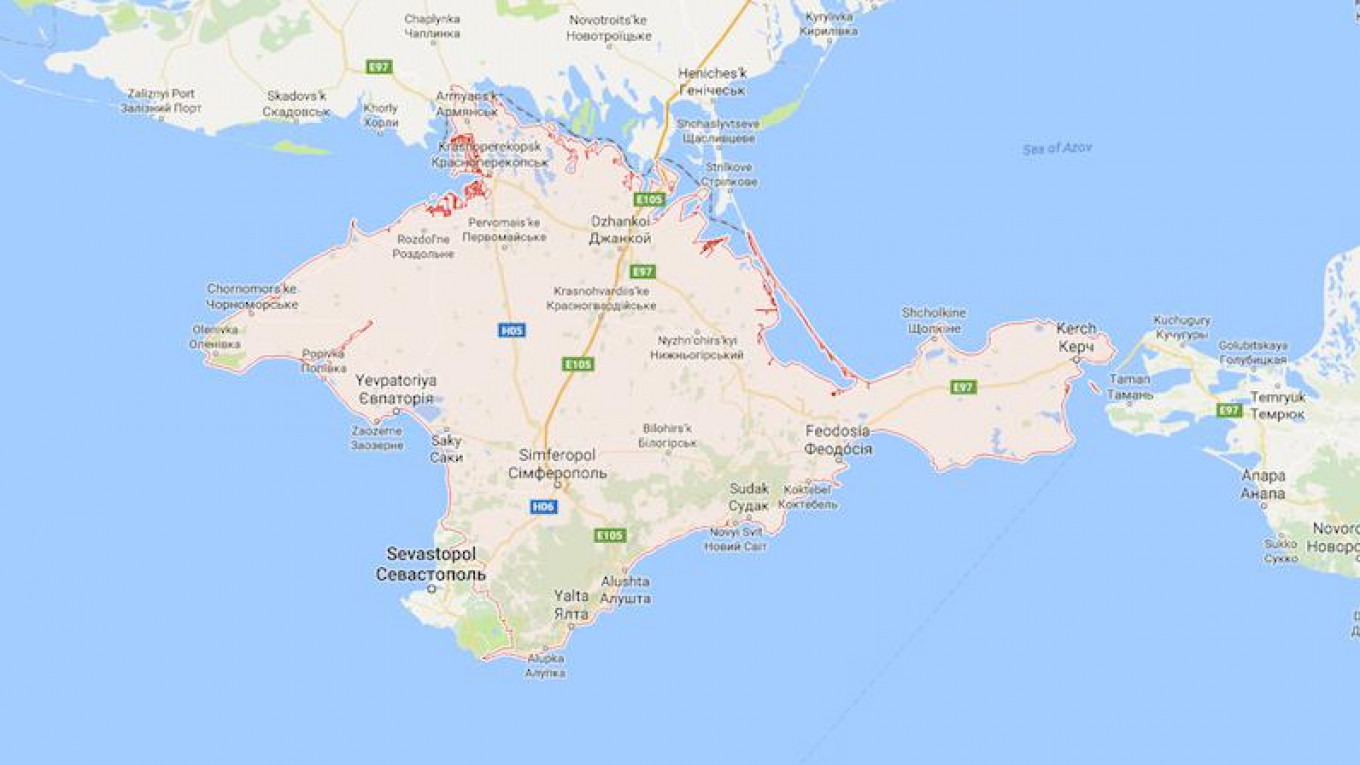

Since Russian troops invaded and annexed Ukraine's Crimean peninsula in March 2014, world topography has struggled to place the international border between the two countries. Research engines, academic textbooks, businesses and other world organizations have come under fire from both the Ukrainian and Russian foreign ministries depending on how they print their maps.

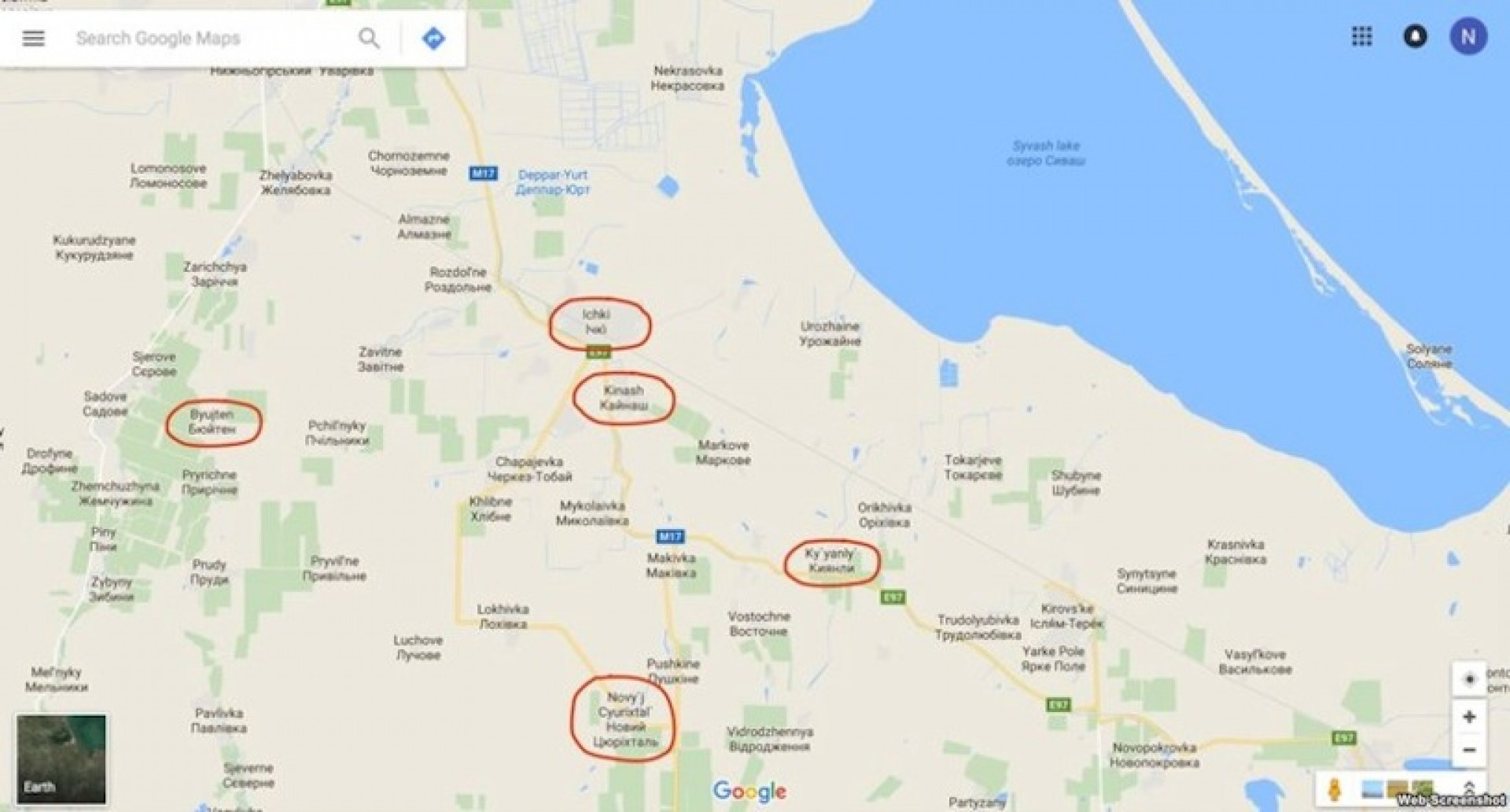

This week, Russia criticized Google for using Ukraine's “decommunized” spellings for street names in parts of Crimea. Google has adopted Ukrainian versions of 900 place names in Crimea.

Russia's Communications Minister Nikolai Nikiforov called the move a “short-sighted policy” and said that he hoped “the mistake is corrected.” “If Google pays so little attention to Russian law and Russian place names then it will not be able to do business effectively on Russian territory,” Nikiforov said.

Crimea's Prime Minister Sergei Aksyonov claimed Google was “pandering to Kiev and feelings of Russophobia in Ukraine,” while another Crimean official accused the company of “topograhical cretinism.”

On Friday, Google reversed its decision and restored the Soviet names for Crimean settlements.

But Google is far from the only company to be caught in the conflict.

Russian search engines

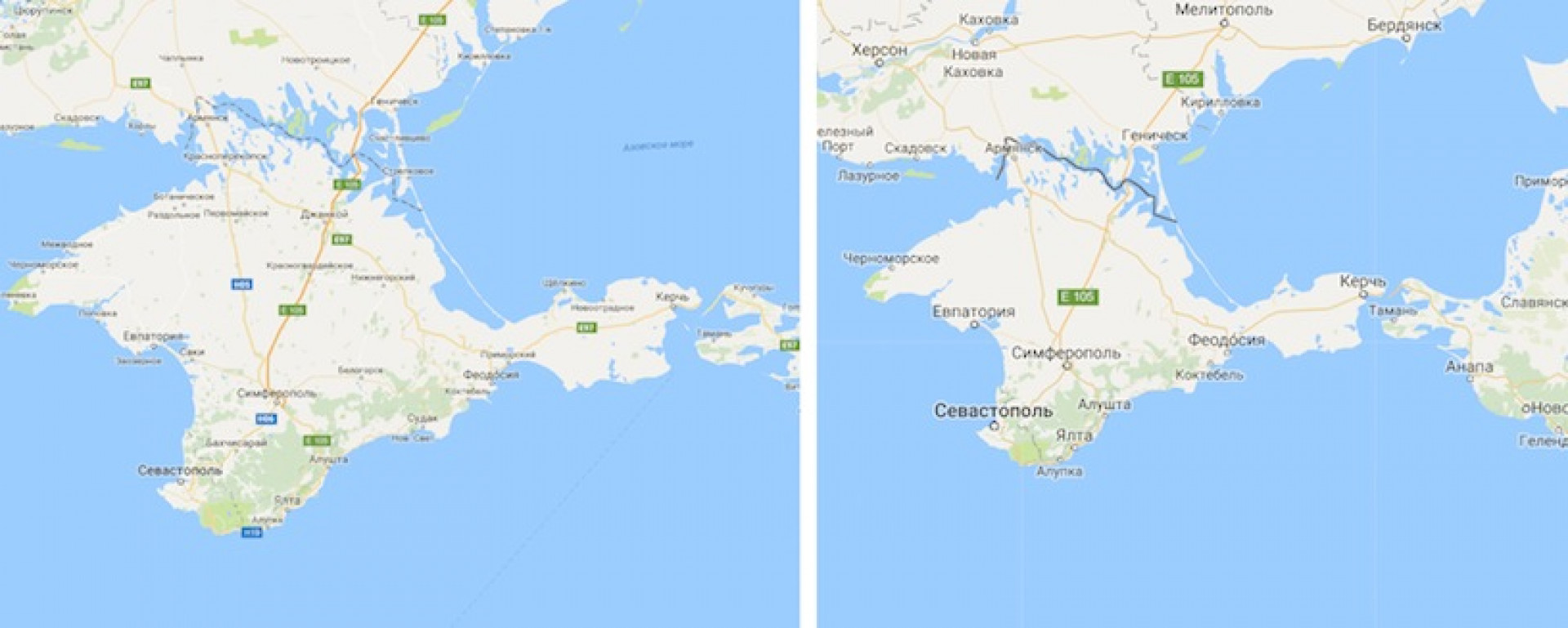

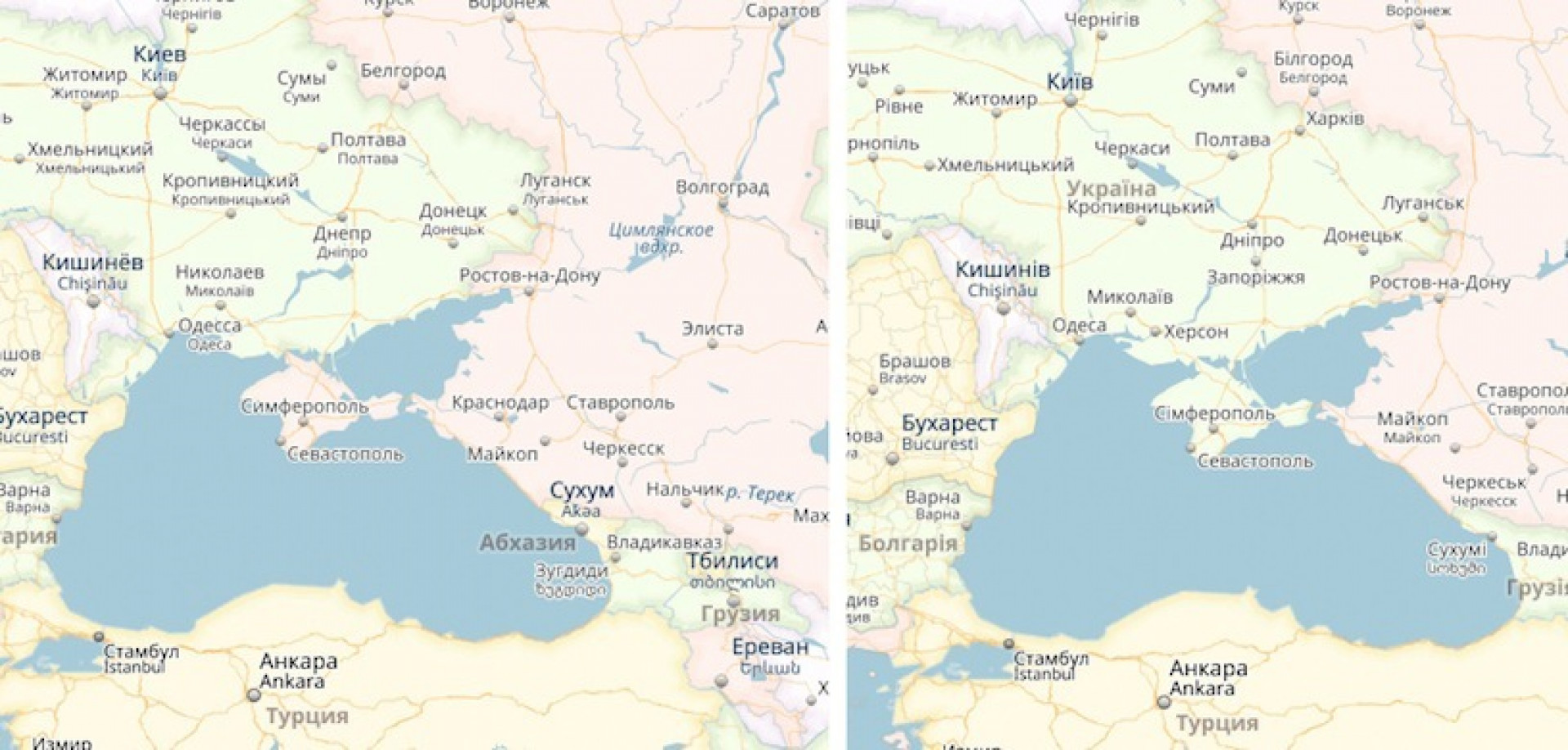

Initially, Russia'a Yandex search engine reacted to the annexation by showing Crimea as Russian on Yandex.ru (the Russian version of the website) and as Ukrainian on Yandex.ua (its Ukrainian version). Russian search engine Mail.ru marked Crimea as part of Russia shortly after the annexation.

Textbooks

Only a handful of countries, including North Korea, Cuba, Syria and Venezuela, have recognized Crimea as part of Russia. Other members of the international community — even staunch Moscow allies like Belarus — have abstained on the issue.

Printing new school textbooks have sparked diplomatic rows with both Russia and Ukraine, depending on where the border was printed.

Kazakhstan angered Russian authorities by ensuring that Crimea remained Ukrainian in academic textbooks. In September 2014, the Kazakh Education Ministry was forced to release a statement on the issue. “The publisher and authors did not fully reflect the position of Kazakhstan or that of the international community in its treatment of the Crimea issue.”

The British publisher Oxford University Press also came under fire for printing a map of Crimea as part of Russia in a geography textbook, prompting complaints from the Ukrainian Embassy in London.

Cuba's Education Ministry, keen to avoid confrontation, printed textbooks with maps showing Crimea as simultaneously part of Russia and Ukraine.

World sporting organizations

FIFA also had to

choose whether to offend Ukraine or the Kremlin. When it unveiled a

promotional video of the 2018 World Cup in Russia, it included Crimea

as part of the Russian Federation. This sparked protest from

Ukraine's diplomats, with additional uproar as Russia is accused of

“kidnapping” Crimean football clubs as part of the annexation.

Global corporations

Coca-Cola made a similar blunder in January when it included Crimea as part of Russia in its advertising campaign, drawing protests and threats of a boycott from angry Ukrainians. The U.S company said that the map, which appeared on its VKontakte page, had been changed by an advertising agency without its approval.

The Crimean annexation was the first time borders were changed in Europe by force and its topographical consequences will live on until the conflict is revolved.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.