In 2002, Boris Nemtsov told a room full of high-ranking Chechens that the North Caucasus republic needed a different type of governance. What Chechnya required was not a system of one-man rule, he argued, but a consensus-based parliament.

“When I left the room, a person with colorless eyes came up to me and said I should be killed for such talk,” the charismatic former deputy prime minister described in his book, Confessions of a Rebel. That person was Ramzan Kadyrov, son of Akhmad Kadyrov, the then-president of Chechnya who had forged an alliance with Moscow after years of brutal war.

“The Chechens around us rushed to say that Ramzan was joking,” writes Nemtsov, who became one of the fiercest critics of the Kremlin. “But I didn’t see any laughter in his eyes. I saw hatred.” For his remaining time in Chechnya, Nemtsov was assigned what he described as a “gigantic” security protection team by Ramzan’s father.

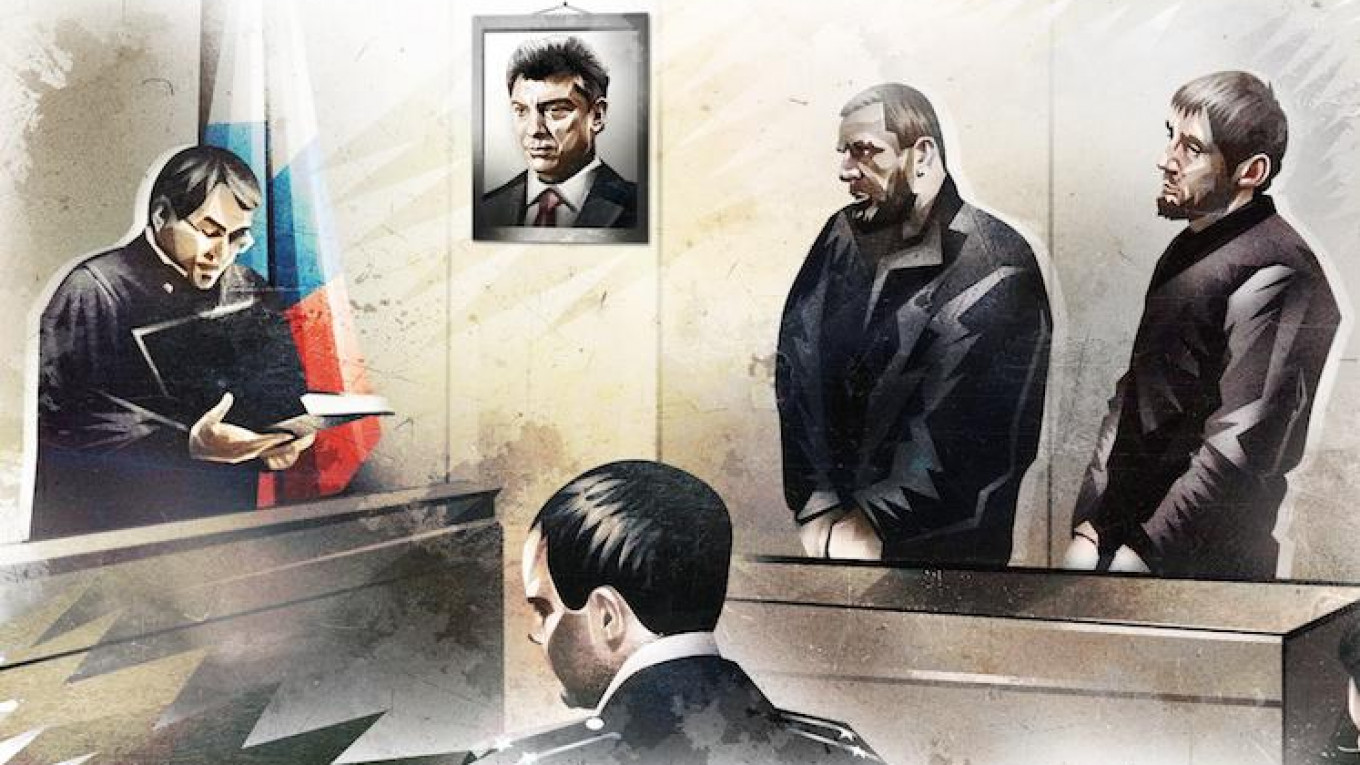

Thirteen years on, in 2015, Nemtsov had no protection when he received four bullets in the back while walking home over the Bolshoi Moskvoretsky Bridge near the Kremlin late one February evening. The gunning down of such a prominent figure just outside the perimeters of Russia’s seat of government shocked the world. Now, as Nemtsov’s murder trial is due to begin preliminary hearings at the Moscow District Military Court on Monday, the larger questions surrounding Nemtsov’s death remain unresolved: Who masterminded the killing? And for what reason?

Nemtsov’s supporters argue the evidence leads right back to Chechnya and Ramzan Kadyrov, who became leader of the republic after his father’s assassination in 2004. The young Kadyrov famously rules the republic with a combination of an iron fist and an active social media presence, often involving loud displays of loyalty to his patron in the Kremlin, Vladimir Putin.

The connection to Kadyrov became apparent soon after Nemtsov’s

murder, according to media reports. As soon as three days after the killing, Putin received a detailed briefing from

FSB head Alexander Bortnikov, the Novaya Gazeta investigative newspaper said.

Several ethnic Chechens were swiftly arrested and charged with planning and staging the attack. Vadim Prokhorov, a lawyer for the Nemtsov family, told The Moscow Times he believes “most” of the defendants in the upcoming trial — Zaur Dadaev, Shadid Gubashev, Anzor Gubashev, Temirlan Eskerkhanov and Khamzat Bakhaev — did indeed play a part in Nemtsov’s murder. But, he adds, others continue to walk free. “There is a reason for this,” he says.

According to Prokhorov, the defendants are the trigger-pullers, while the organizers remain at large. Last April, the team of lawyers handed investigators a list of people they believed should be questioned. “To our great regret, almost nothing has been done to identify the contractors and organizers of the murder,” says Prokhorov.

Instead, the lead investigator on the case, congratulated for making quick progress, was replaced. At the time, Nemtsov’s supporters argued it was a sign the Russian leadership wanted to put a lid on the investigation.

The investigators’ trail has stopped at Ruslan Mukhudinov, the driver of a top commander of Chechnya’s Sever armed battalion, as the likely brain behind the attack. But to Nemtsov’s supporters, Mukhudinov is just another middle-man. They point to his former employer, Ruslan Geremeyev, a relative of some of Kadyrov’s closest associates.

“We’re practically sure he played a central role and that the organizing of this murder went through him,” says lawyer Prokhorov.

The two people in question, however, will be conspicuous at the trial only by their absence. Mukhudinov has gone missing, and when Russian police came for Geremeyev in a Chechen village, they were met with armed men and repelled.

Without them, the investigation has hit a wall that is

unlikely to crumble. “Don’t expect any of the contractors to appear on the

defendant’s bench,” says journalist Grigory Tumanov, who has followed the Nemtsov case since the beginning.

Kadyrov meanwhile has denied all involvement and stood by his men. In the month following the murder, he described main suspect Dadaev, a former deputy commander in the Sever batallion, as “a true patriot.” Only interference at the highest level could put the case back on track. The lack of progress suggests Putin may have already made his choice.

While Kadyrov’s alleged involvement in the high-profile killing might plausibly have irked Putin, such feelings are trumped by a desire to preserve stability in the North Caucasus. As Nemtsov described in his book: “Kadyrov has a fantastic chance to blackmail Putin. He can decide to go into the mountains at any point […] Chechnya is a region that is being ruled by a person who ‘by agreement’ is temporarily loyal to the Kremlin.”

Kadyrov was temporarily reappointed to his post in March, pending upcoming parliamentary elections in September which, with Putin’s backing, he is practically guaranteed to win.

“The support is symbolic, but it is enough to have symbolic support,” says Grigory Shvedov, editor-in-chief of the Caucasian Knot news portal. “There has not been a fundamental change in their relationship.”

The Chechen leader also shows no sign of laying low, famously posting a video of another opposition leader, Mikhail Kasyanov, in the crosshairs of a rifle.

Meanwhile, Russia’s security services are less willing to forgive. The FSB has had longstanding irritation with Chechnya’s leadership. The brash murder of Nemtsov in the center of Moscow — the FSB’s home turf — eroded what little patience remained.

“Even before Nemtsov’s murder their relationship was poor, but now it’s really bad,” says political analyst Stanislav Belkovsky. “The Investigative Committee and the FSB approach Kadyrov with heightened suspicion and want, if not his resignation, then a limitation of his role.”

With the supposed contractors of the killing out of reach, the big questions are likely to remain unanswered, says Tumanov. In fact, “as more details come out during the trial, it is likely to lead to even more questions,” he says.

Meanwhile, the prosecutors’ main trump card will be to attract media attention to the case. They could call upon the very top of the establishment to testify, including on Kadyrov himself and the head of National Guard, Viktor Zolotov, who, in theory, is accountable for the actions of regional battalions such as Sever, Tumanov says.

But the court proceedings will likely present little threat to the Chechen leader. With Putin’s support and no debate in Chechnya over the trial, Kadyrov, with his constant presence on social media, might be his own biggest enemy.

“The only way the trial can further harm Kadyrov’s reputation is if he himself makes a public statement,” says Shvedov.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.