Last week Moscow's International Jewish Film Festival came to its close. The winner of the Grand Jury Prize was David Novack's "Finding Babel," a documentary combining Isaac Babel's fiction, archival footage and interviews with an ethereal animation technique. The result is a powerful exploration of the links between the life and works of the Ukrainian-Jewish author who fell afoul of Stalin's regime.

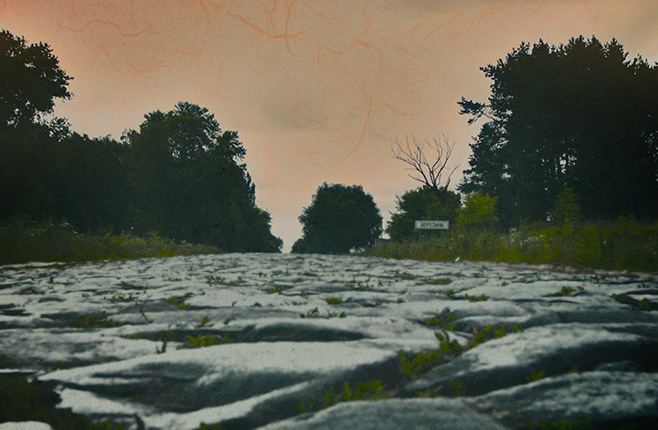

The documentary features Andrei Malaev-Babel, Babel's grandson, as he travels through Russia, Ukraine and France in a quest to link his grandfather's life with his fiction. Andrei, a professional actor, was recorded reciting Babel's works in geographically significant locations for the documentary.

In an interview with The Moscow Times, director Novack explained his decision to structure the film around Malaev-Babel. "My feeling as an artist, and Andrei's, was that by tracing Babel's stories and life, Babel himself would dictate the direction and emotion of Andrei's journey and a film would evolve from that experience," he said. "This is exactly what happened. What emerged is much more a narrative tale of the essence of the writer than a didactic documentary filled with facts."

Babel, who was born in Odessa, moved to St. Petersburg (then Petrograd) in 1915, where he worked as a journalist and writer. An astute observer of human behavior, Babel documented and filtered the reality around him into his fiction. He was in essence a journalist who could seamlessly transmute his experiences into his art.

It was in this skill that lay Babel's greatest contradiction. "He saw the beauty and triumph of humanity on one hand and the inevitable horrors that it ultimately brings on the other. In many of his characters, he embedded both of these to show us that good and evil exist together in people and in nations," said Novack.

Timeless Conflict

The powerful narratives in Babel's "Red Cavalry" — published in the 1920s — brought Babel international acclaim. The work, based on diary entries from his experiences in the Polish-Soviet war, brought the dark reality of conflict in modern day Ukraine to people's attention. While shooting for the documentary took place before the current conflict, it's a stark reminder of how easily conflicts in this part of the world can arise.

"History is a constant dance between stability and conflict between tribes, serfdoms, religions, kings, nations. Babel alludes to the history between Russia and Ukraine is several of his stories," said Novack. "Maria," a play which was shut down at its dress rehearsal stage in 1935 and only performed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, is one of these. Maria at one point states, "Russia has denigrated them [Ukraine] for centuries."

"No matter what position one takes on the current situation, it's easy to see that Babel recognized ethnic conflict between Russians and Ukrainians and chose to imbue a strong, central, Russian character with empathy for Ukrainians," said Novack. "Babel was a visionary. And somehow, he took us down a path in which we could be visionaries, too."

Yiddish Humor

Much loved by Russian-speaking audiences, Babel is less well-known in the West, despite many translations of his work. Many readers will have come to Babel through "Odessa Tales." "In Odessa Tales," Novack said, "he captures the unique humor of the Odessite dialect which deeply embodies the duality, causing the reader to laugh aloud just as, for instance, Benya promises to kill all dairy farmers except for the one whose daughter he wishes to marry. The humor of Odessa does not translate well into most languages, but it is precisely, I believe, why he is so loved in the Russian-speaking world," said Novack. "As an English reader, I first was able to access this humor when I infused my reading with my grandmother's Russian-Yiddish accent. Only then did it totally make sense and crack me up."

Reopening the Archives

It was in many ways a grueling experience for both Andrei and Novack to relive the hardships and isolation Babel suffered during the latter part of his life. In 1935 Babel travelled to Paris and announced he was becoming master of the new literary genre of "silence." His satirical writing has been tolerated for some time, but things were turning sour.

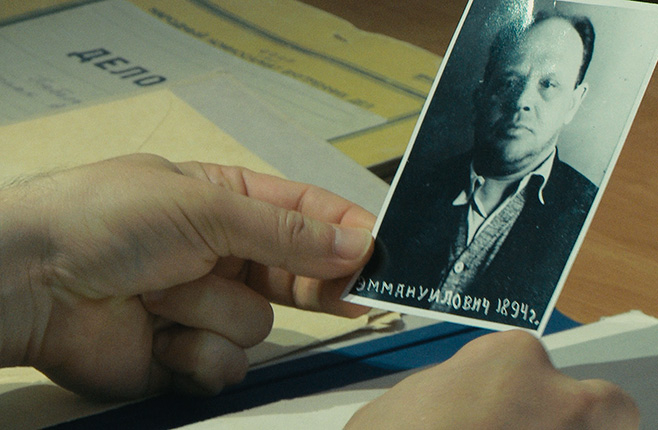

In 1939 after returning to Russia, he was arrested at his home in Peredelkino, a writers' community just outside Moscow. Many of his works were also seized, and for fifteen years his widow, Antonina Pirozhkova —who appears in the documentary — did not know his fate. He had been shot in his cell in Butyrka prison in 1940. Access to Babel's NKVD file could reveal some of the facts surrounding his death and work, but much of his opus was confiscated, destroyed or simply lost in the years following his arrest and execution.

"Empathy is the key to this kind of directing. It can't be forced or faked. It requires opening your heart to the journey and internal conflicts of another and taking the emotional plunge with them," said Novack. "Several times, I found myself crying on location. In some cases it was because Andrei was going through something difficult and I shared it as much as I could. At other times, it was because something magical happened, serendipitously, that was such a strong sign of being on the right path that it brought me to tears."

Babel may have written about specific events he witnessed, but his overarching themes make his work resonate as much today as when they did nearly a century ago. Babel dreamed of an "impossible international" where nations and political parties would not wage war against each other. At the same time he predicted contemporary divisions resulting in collapse with his epithet "everything repeats itself…with striking exactness."

For more information about the film, see findingbabel.com.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.