In late May, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev inadvertently caught the mood of the nation.

On a tour of Crimea, Medvedev was confronted by an angry woman, who demanded to know when the government planned to raise her 8,000 ruble ($125) per month state pension. "You can't live on this!" the woman cried. "Prices are rising madly."

The prime minister's reply was frank. "There's just no money," he said, struggling to be heard above the complaints. "When we find the money — we'll do it." Then he turned to leave with the parting words: "You hang on in there. Have a good day. All the best."

Captured on camera, the remark went viral. Commentators and social networks fizzed with ridicule. After two years of confrontation with the West over Ukraine and 16 years of President Vladimir Putin, Medvedev seemed to have exposed the extent of Russia's economic and political dead end.

For the first time in years, state pension payouts have fallen behind rising prices. The economy is shrinking for a second consecutive year. Without fundamental reform, a long period of stagnation beckons.

Against this backdrop, some 10,000 businesspeople, officials and journalists gather in St. Petersburg on Thursday for Russia's version of the Davos economic forum. The Moscow Times looked at the key political and economic questions that will dominate the event.

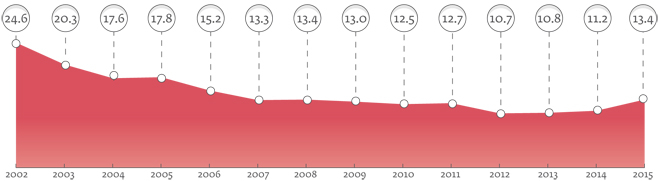

Poverty rate within the Russian population

Sanctions

Ever since Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula and fomented violent separatism in eastern Ukraine in early 2014, the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum has been the site of political drama.

Together with their allies, the United States and the European Union imposed sanctions on Russia to limit its access to international capital, investment and technology. They also put heavy pressure on their businesses to boycott the forum, which is hosted by Putin.

Two years on, that pressure is more patchy. As in previous years, not a single U.S. official will attend the forum. Most Western companies, however, responded to the boycott not with fewer delegates, but by sending more junior delegations. And some big political names do plan to attend, including Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission, and Matteo Renzi, Italian prime minister.

The atmosphere has shifted, says Alexis Rodzianko, the head of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia. This year, he says, "there is no expectation for an increase in sanctions and some hope that maybe we're looking at a horizon where sanctions might be lightened."

This is not the result of any Russian retreat. The war in eastern Ukraine, which has killed 9,000, simmers on, with the death toll rising weekly. Crimea, now a Russian region, will have an official delegation in St. Petersburg and a stand displaying local investment opportunities.

Many in Europe are frustrated with sanctions. Together with Russian countermeasures, they have cost companies billions of dollars. The EU will likely prolong its sanctions at a meeting later this month, but diplomats have warned of a showdown later this year when the measures again come up for renewal.

On June 8, France's senate voted to "gradually and partially" lift sanctions by a margin of 302 votes to 16. The vote is non-binding on the government, but was the latest sign of discord.

Russian officials, meanwhile, make a show of not caring about sanctions. Russia has "fully adapted," Economic Development Minister Alexei Ulyukayev said last month. "Honestly, I don't see any macroeconomic effect [from sanctions] at all."

That may be bluster. But Capital Economics, an analysis firm, says the lifting of EU sanctions would likely add only 0.5 percent to Russian economic growth.

Oil Price

In fact, the key driver of the Russian economy is the oil price.

Here, there seems at least to be some good news. Crude prices have almost doubled since hitting 13-year lows of less than $30 per barrel in January.

But prices are still far below last year's levels. Even with the rebound, the Russian Central Bank forecasts an average of around $40 per barrel for this year and in 2017. That would be around $15 dollars per barrel less than the average last year — when Russia's economy shrank by 3.7 percent.

What's more, Russian oil output, which has risen to post-Soviet record levels of close to 11 million barrels a day, will likely start to fall this year as lower prices, increased taxes and the West's sanctions starve the sector of long-term finance, according to a recent report by the Fitch ratings agency.

The collapse in oil prices has transformed the structure of the government's finances. Before 2015, more than half of budget revenues came from taxes on the energy sector. Last year, the percentage fell to 43 percent. In the first quarter of this year, it was just 34 percent.

That means that the government has to find other sources of cash.

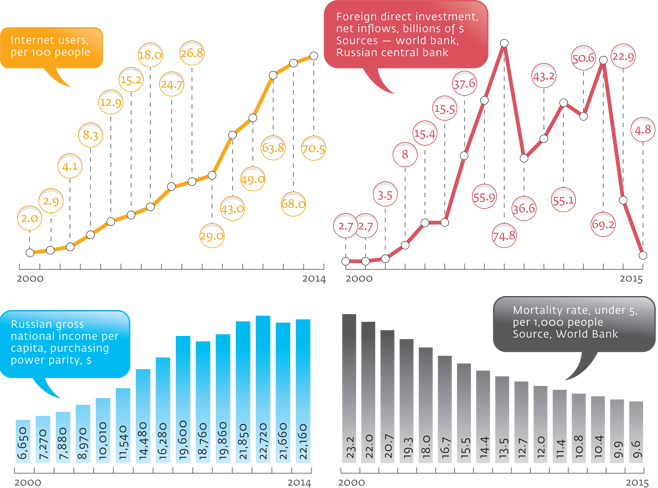

Russia in numbers

Growth vs. Stagnation

One thing helping the economy is the ruble. Russia was able to avoid a deep crisis thanks to the devaluation of its currency. Even as the dollar value of oil fell by more than half, its value in rubles stayed roughly the same. This allowed oil companies and the government to maintain their ruble spending.

The devaluation also created economic opportunities.

The weak currency has forced more Russians to vacation at home and made it cheaper for foreign tourists to visit. The number of Chinese tourists coming to Russia rose to more than 1.3 million in 2015, according to the Federal Tourism Agency — a 64 percent increase from the year before.

Agricultural production is also rising — by 2.8 percent in the first four months of this year, according to Ulyukayev, the economic development minister. Last year, agricultural exports rose to some $20 billion, outstripping arms exports.

"The main message from officials at the forum will be that Russia has proven much more resilient in the face of sanctions and low oil prices than was expected," says Chris Weafer, a Russia veteran and partner at consultants Macro-Advisory in Moscow.

But these bright spots have many caveats. Weafer's analogy is a body that has fallen off a building and smacked into the pavement. "The good news is that it's not falling any further," he says. "The bad news is it's broken."

Analysts expect the economy to start to grow again later this year. But beyond that looms a long period of economic stagnation. Many Russian companies are accumulating profits, but few want to invest.

Part of the problem are high levels of risk and insecurity. If, for example, the oil price rises and strengthens the ruble, those who bet on industries that benefit from a weak ruble could lose their investments.

More fundamentally, global growth has slowed, which means the world wants less of the metal, oil and gas that Russia produces.

And at home, Russians are spending less. Price increases and stagnant wages have made people markedly poorer. Almost nine in every 10 Russians have seen their incomes fall in real terms over the past year, according to a new report by PricewaterhouseCoopers, the financial services firm. The impoverishment is even deeper outside Moscow, which has maintained relative prosperity, the report found.

The investment climate has also become more dangerous, says Andrei Movchan, an economist at the Carnegie Center in Moscow and a former money manager. He says the recession has shrunk the pool of available assets and made those with links to officials and law enforcement more aggressive in their efforts to make money — by fair means or foul.

Meanwhile, Ulyukayev says the working population is due to shrink by between 200,000 and 300,000 people per year for the next decade. The number of pensioners without savings teetering on the edge of poverty will rise. "Even with $100 oil, we won't be able to grow at more than 1.5-2 percent per year without structural reform and an improvement in the investment climate," says Elvira Nabiullina, the head of the Central Bank.

Growth of less than 2 percent would result in Russia lagging behind the global average, further reducing the country's competitiveness and relative wellbeing. In effect, says Movchan, Russia will be relegated to a second or third league of nations: "It'll be rivaling not Portugal, for example, but Romania and Vietnam."

Many richer Russians are already losing patience. A recent survey by headhunters Kontakt suggested that more than 40 percent of Russian executives were ready to emigrate.

Reform

Faced the threat of stagnation, the government wants to act.

The Central Bank in June reduced its benchmark interest rate for the first time in nearly a year, to 10.5 percent, making it cheaper to borrow.

The government meanwhile plans to sell shares later this year in companies such as oil producers Rosneft and Bashneft, and Alrosa, a diamond miner. This should earn money for the budget and encourage better management. But Putin has said he will accept only sales to strategic investors or Russian buyers. Analysts fear that such privatization could see the state's preferred candidates snap up assets with funds from state banks — perhaps deepening existing Russian cronyism.

Many ministers are thinking strategically. In early June, Ulyukayev published in Vedomosti, a business newspaper, a manifesto of state measures to boost investment by 7-8 percent per year and double the country's growth potential to 4 percent. A day later, Medvedev blessed a plan to double the share of small- and medium-sized businesses in the economy from 20 percent to 40 percent — close to the level common in developed nations.

That problem is that these solutions rely on state intervention and their advocates are powerless, says Movchan. Real influence is held not by technocratic ministers, but by Putin and a small circle of advisors, many of them drawn from the country's law enforcement structures.

Former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin has in recent months emerged as a standard-bearer for structural reform. In April, he was appointed to an advisory role to the president. The understanding is that he will lobby for prudent government spending, greater productivity and a trimming of the state. But the extent of his real influence is unclear.

Political Change?

Few people expect the system to fall apart any time soon. The country still has sizable hard currency reserves and a healthy trade surplus.

The economy continues to function, even if poorly. Rodzianko said that U.S. multinationals surveyed by the American Chamber of Commerce planned to raise investment roughly 15 percent above last year, admittedly from a low base.

Unrest has flared in some towns, particularly industrial centers, which have suffered layoffs and wage cuts. But protest remains sporadic. Ahead of parliamentary elections later this year, the authorities have tightened their grip on civil society and media.

Four out of every five Russians still say they support Putin. "Society values stability much more than prosperity," says Movchan.

With change far from the agenda, many Russians have instead taken refuge in self-mockery. Following Medvedev's pensions gaffe, the songwriter comedian Semyon Slepakov recorded his own "prime ministerial address to the people." The ditty riffs policy breakthroughs with international trade deals, spearheaded by officials working for the people all hours of the day. The video has been viewed 7 million times since it was uploaded in early June.

"I'm glad to tell you what we've achieved in recent years," trills Slepakov's Medvedev.

"We have results!

There's just no money."

Contact the author at p.hobson@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter at @peterhobson15

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.