Bidding opened suddenly on the morning of May 23. After a three-year absence from international markets, and with very little warning, Russia announced it wished to borrow billions of dollars.

The Finance Ministry sought to help finance a yawning budget deficit caused by the low price of oil. It also wanted to see if Western investors, who have largely avoided Russia since the Ukraine crisis, would buy the country’s debt.

It appeared strikingly successful. The plan was to sell up to $3 billion in 10-year, dollar-denominated eurobonds. The yield, at around 4.75 percent, was generous compared to Western bond markets. Within a few hours, banking sources were saying that orders had been placed worth $5.5 billion.

But there was a snag: the sources said very few of the buyers were foreign. So the sale was extended into the next day in the hope of attracting extra bids, mainly from Asia.

When orders closed in the evening on May 24, the Finance Ministry said demand had hit $7 billion, and it had sold bonds worth $1.75 billion. More importantly, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov announced that more than 70 percent of that — around $1.3 billion — had been bought by foreigners. This showed the “high level of trust in Russia as an issuer,” Siluanov said.

However, some had their doubts. Why, if there were so many buyers for the bonds, did Moscow sell so few? And with so many Western investors saying they were shunning the sale, who were the foreigners who bought?

“‘Foreign’ might well be offshore Russian,” tweeted Timothy Ash, emerging markets economist at Nomura in London. Market sources told Vedomosti, a Russian business daily, that local buyers had submitted outsize bids to artificially inflate demand for the eurobonds, and may have cycled money through the United States and other countries to give the appearance of foreign investment.

The Sanctions Effect

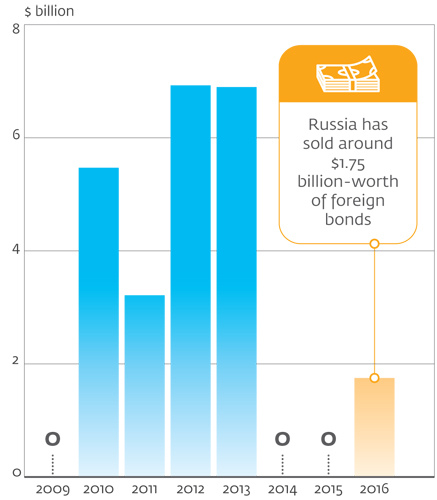

Russia last borrowed on international markets in 2013. Then, it raised $7 billion. But the following year, Western governments slapped financial sanctions on the country after it annexed Crimea and backed separatist militias in Ukraine.

The government itself was not blacklisted; the sanctions targeted only individuals and companies. But they made many Western banks wary of dealing with the Russian state, which owns and runs several sanctioned firms.

Moscow had sought to try international bond markets earlier. In February, the Finance Ministry sent letters to 25 foreign banks inviting them to underwrite a eurobond sale. But fearful of breaching sanctions and under pressure from their governments, none took up the offer.

However, if the West’s banks were leery of the bond sale, other industries had no such qualms. The prospectus for this week’s sale lists British lawyers Linklaters and U.S. firm Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton as legal advisors. The listing agent is Ireland’s Walkers Listing & Support Services. Aided and advised by these firms, Moscow decided to go ahead with the bond issue anyway.

Russian sovereign international debt

The sale’s sole organizer was VTB Capital, an arm of Russian state banking group VTB that itself is sanctioned. To assuage worries, VTB’s prospectus promised that money raised in the bond sale would not be used to finance sanctioned companies. But it said “no assurance can be given” that international clearing houses would handle the bonds, and that instead a single Russian clearing agency would be servicing them.

Clearing houses such as Euroclear and Clearstream are seen by investors as guarantors of the trustworthiness and tradability of bonds. Neither has signed up to handle the bond. And neither Barclays nor JPMorgan have included Russia’s bond in their indexes.

Local Dollars

Whether or not foreign interest in the bond sale was inflated, local demand was solid, analysts say.

That might even have been the way the government planned it. Russia’s financial sector has built up a large stash of hard currency since the start of the Ukraine crisis, when sanctions and the falling oil price caused financial turmoil and a rush to buy dollars to protect against a collapse of the ruble.

A year and a half later, “banks had nowhere to put their dollars,” says Dmitry Polevoy, chief Russia economist at ING Bank in Moscow. The eurobond offer was an effective way to release those funds, and at the same time help finance the budget deficit, he said.

That deficit, expected this year to reach some 3-5 percent of GDP, or between $35 and $60 billion, is one of the government’s major headaches.

To cover the shortfall Moscow plans to privatize major state companies and draw down its $50 billion reserve fund. But both these moves are unpopular — state corporate bosses are resistant to going private and authorities fear a painful fiscal crunch if the reserve fund is spent before the economy recovers or oil prices rise. Meanwhile, government debt is low, at around 13.5 percent of GDP.

Even if its success was limited, the bond sale shows that Russia is out of crisis, says Neil Shearing, head emerging markets economist at Capital Economics in London.

“This sends a message,” he said. “The economy is through the acute phase of its crisis, and sanctions will no longer put a hard stop on the government’s access to hard currency debt.”

Contact the author at p.hobson@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter at @peterhobson15

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.