Дармоéд: freeloader

I like a stroll down memory lane as much as the next guy, but lately a spate of possible "new" laws seems a bit too close to the "old" laws for comfort. I'm thinking about the discussion concerning налог для официально неработающих трудоспособных граждан (a tax on able-bodied citizens who are officially not working). My first question is, of course, what constitutes официально (officially)? And my second question is: Вы чё ребята, спятили? (Yo, guys, you nuts or what?)

However you dress this up with words like налог (tax), an "officially not-working able-bodied citizen" is called тунеядец and what this not-working citizen does is called тунеядство. Тунеядство is a compound word formed from туне, an old word meaning "for free, without pay" and ясти, another old word meaning "to eat." So тунеядство is "eating for free." This is дармоед and дармоедство in more modern Russian. This is exactly what English speakers call freeloading, mooching, sponging, or bumming.

Alas, those words are a bit too slangy for this bureaucratic concept, which is usually rendered as "parasitism." In fact a synonym for this in Sovietese is социальный паразитизм (social parasitism).

Let's re-examine some of the lexicon of social parasitism in case it makes a full comeback.

From the very start of Soviet power, тунеядство was a Very Bad Thing. In December 1917 — that is, two months after the Revolution — Vladimir Lenin wrote about it: Тысячи форм и способов практического учёта и контроля за богатыми, жуликами и тунеядцами должны быть выработаны (We must develop thousands of forms and way to register and discipline the affluent, crooks and freeloaders). Among the methods used successfully around the country, Lenin noted: поставить их чистить сортиры (making them clean the outhouses) and расстреливать на месте, одного из десяти, виновных в тунеядстве (shooting on the spot one out of ten people guilty of not working).

I bet that got everyone's attention.

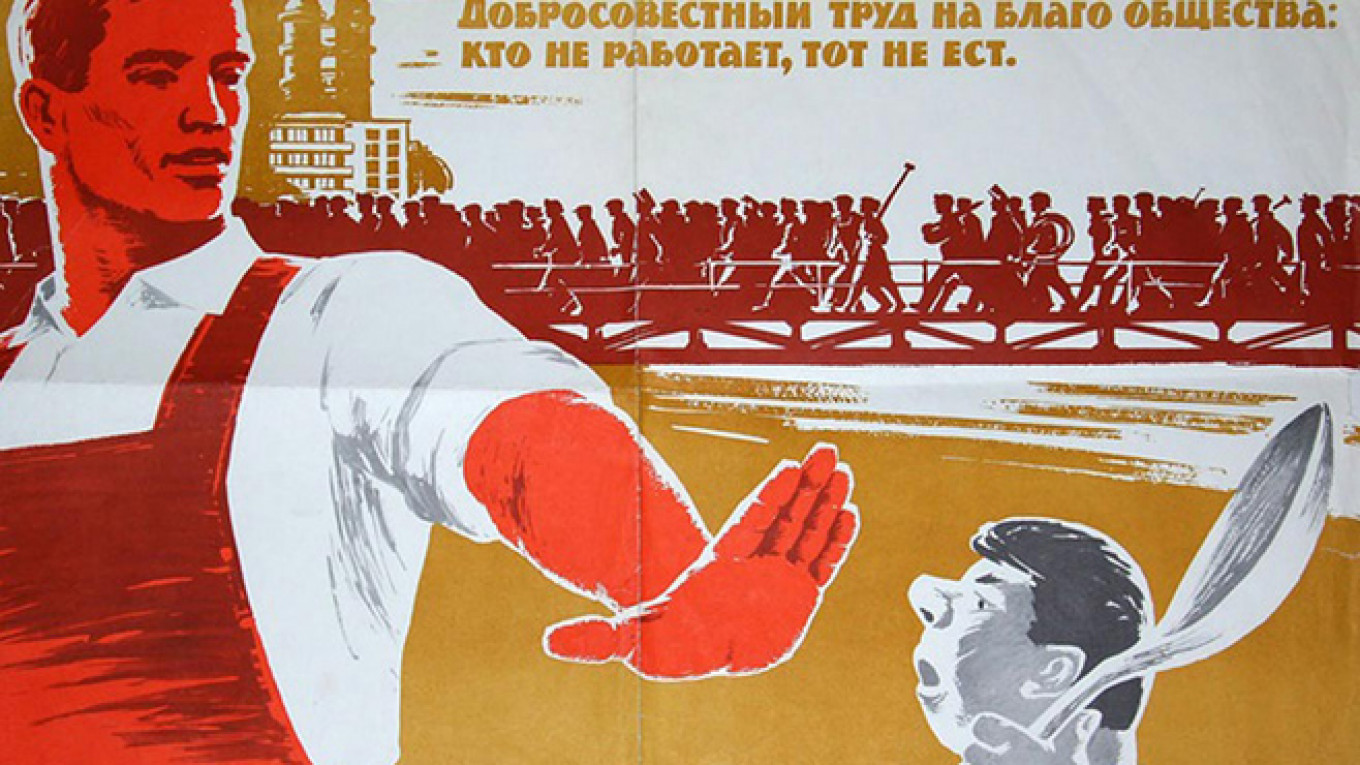

By 1936, working wasn't just a right, but an obligation written into the constitution: Труд в СССР является обязанностью и делом чести каждого способного к труду гражданина по принципу: "кто не работает, тот не ест" (Labor in the Soviet Union is an obligation and a matter of honor for every able-bodied citizen according to the principle: "he who does not work, does not eat.")

Not working — тунеядство — was defined this way: когда лицо уклоняется от общественно полезного труда и проживает на нетрудовые доходы более четырёх месяцев подряд или в общей сложности в течение года (when a person eschews socially useful labor and lives on non-earned income for more than four months in a row or a total of four months over the course of the year).

Общественно полезный труд (socially useful labor) was труд в санкционированной государством форме (labor in a form sanctioned by the state). That's what got Joseph Brodsky in trouble. When he was on trial for тунеядство in 1964, he said he worked as a poet. But the judge asked: А кто это признал, что вы поэт? (Who said that you were a poet?)

Today you can rent out your apartment, self-publish your poetry, or live off your stock dividends — just pay income tax. But if you are officially not working, you may also have to pay a no-income tax.

Всем ясно? (Got it?)

Michele A. Berdy, a Moscow-based translator and interpreter, is author of "The Russian Word's Worth" (Glas), a collection of her columns.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.