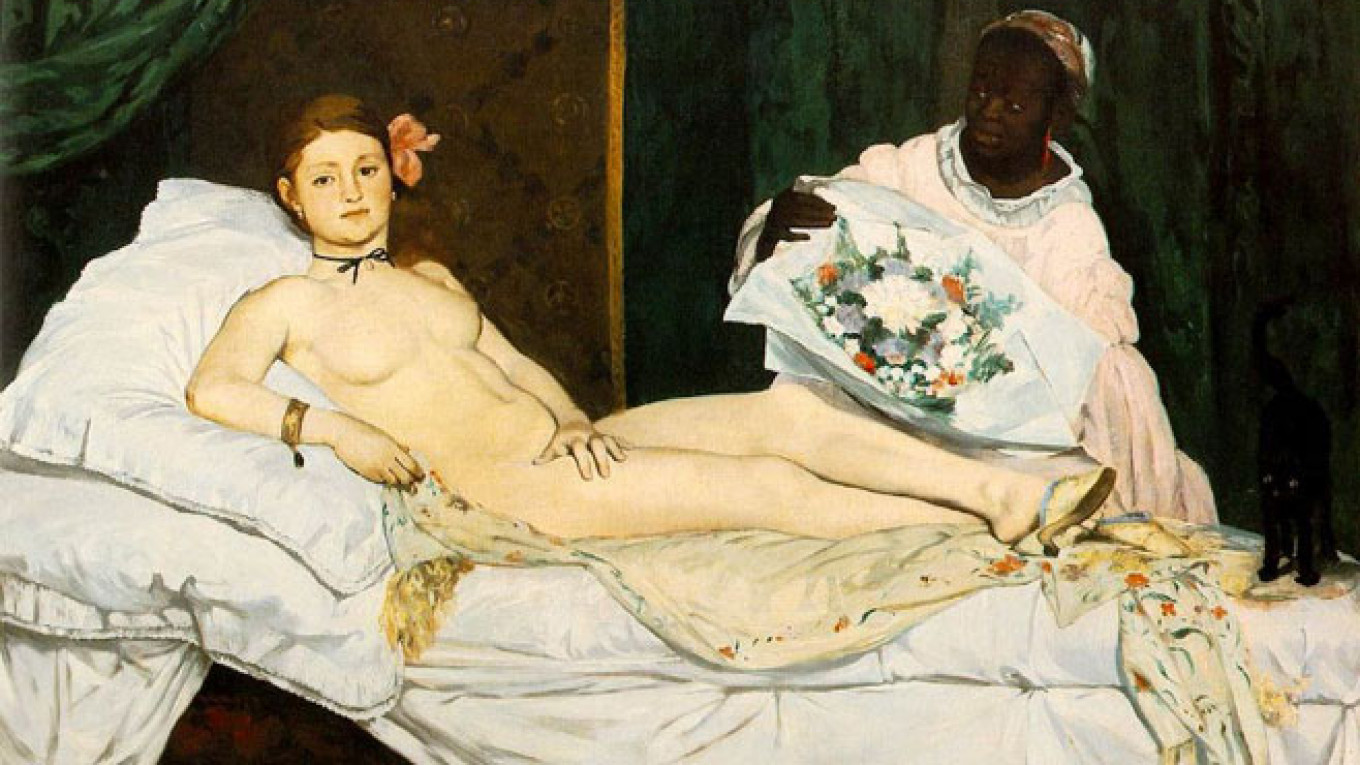

Edouard Manet's painting of a nude woman reclining on a bed shocked and scandalized the French public when it was first exhibited at the 1865 Paris Salon. In an unprecedented act of cultural diplomacy, this April the painting left its home at the Musée d'Orsay for only the second time in its history to appear in a new 4-work exhibition at Moscow's State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts.

Enduring Appeal

The exhibition explores how artists throughout history have chosen to depict the beauty and sensuality of the nude female body. Considered to be one of Manet's most significant works, "Olympia" forms the centerpiece of the series. Three works from the Pushkin's collection offer different interpretations of the ideal female form: Paul Gauguin's "Te Arii Vahine" (1896); "Woman with a Mirror" (early 1520s) by Giulio Pippi, and a copy of Praxiteles' sculpture "Aphrodite of Knidos."

Nudes have long become an accepted and universal subject in visual art. The first artwork in the exhibition is a copy of the "Aphrodite of Knidus" sculpture by Greek sculptor Praxiteles of Athens, completed in the 4th century BC. Praxiteles was the first artist to depict a fully nude female, and his sculpture represents the goddess Aphrodite as she prepares for her ritual bath.

When Manet painted his "Olympia," he took Titian's "Venus of Urbino" as his model. Yet rather than painting in the accepted artistic tradition, which dictated that paintings of figures should reflect Biblical or mythological themes, Manet chose to paint a women of his time. A real woman — widely believed by critics to be a prostitute — who transgresses the paradigms of classical painting. While Olympia reclines in the same position as Titian's Venus, she fixes the viewer with a powerful gaze. It is the ambiguity of this gaze — colluding, contemptuous or simply ambivalent — that draws you in. And with it Manet denies the strict classification of female sexuality depicted by his forbearers.

A Modern Venus

Manet's "Olympia" seems to be cold, hard — even calculating. She exudes none of the soft femininity of Titian's "Venus," Praxiteles' "Aphrodite" or Guilio Pippi's "Woman with a Mirror," the other paintings in the exhibit. Her skin is almost luminescent, her body is clearly being presented as a commodity, but you can't help but feel she is the one holding the power. The woman's black maid presents her with a bouquet of flowers — presumably from an admirer — but "Olympia" pays not the slightest bit of attention. As you stare longer at her you begin to feel almost confronted. It's no wonder the prim conservatives at the Paris salon were shocked at the bold depiction of a female waiting for her lover.

But it wasn't just Manet's subject that challenged the feminine ideal, it was also his style of painting. Manet stripped away the academic technique traditionally associated with nude portraits. The paint strokes are rough, quick and in many ways strikingly two-dimensional. Olympia herself doesn't adhere to the hallmarks of classical Renaissance beauty. Her face is asymmetrical, her hair scraped back and her location clearly depicted as a Parisian apartment building. Even her powerful gaze is somewhat unusual. Her dark pupils are of slightly different sizes, the lids of her eyes heavy over them. One member of the jury at the Paris salon called Manet "the apostle of the ugly and repulsive."

The final painting in the exhibition shows a Venus very different from both Manet's "Olympia" and the artworks which precede it. Gauguin's naked Tahitian beauty almost forms one with the exotic and fertile landscape, depicted in vibrant colors, around her. Named "Te Arii Vahine" (The King's Wife) the painting in many ways subverts European tradition while also nodding to it. Her pose mimics that of both Titian' "Venus" and Manet's "Olympia," but the setting, style and colors make it a fresh and uniquely modern perspective on beauty.

The Universality of Beauty

Despite controversy over how to capture the female form, the central theme of beauty is a universal theme in visual art. Why is this?

"Because it is one of the eternal themes that artists are concerned with when they meditate on the eternal problems of concern to humanity and the individual," said Marina Loshak, director of the Pushkin Museum, in a written statement to The Moscow Times. "And, of course, these problems of beauty, love, history, the beauty of love in its various incarnations, the different philosophical twists that exist around it, and different reflections on it, and all kinds of stories — they are linked, of course, with love, with beauty, with death and with these eternal themes."

And the arrival of "Olympia" has certainly been a hit with Muscovites. Masha, a student, has visited the exhibition on a whim while at the Pushkin Museum. "I hadn't expected the brightness and depth of the colors. The paintings, especially this one [the portrait by Gaugin] are so striking. It's wonderful that there has been an opportunity for "Olympia" to travel out of France for the first time and I hope there are more opportunities for collaborations of this kind."

Cultural Bridges

It seems that there is hope for further collaborations between the Pushkin Museum and the Musee d'Orsay regardless of any political tensions between their countries. "The point is that our strategic partnership with the Musee d'Orsay has not been interrupted. It is very durable, it is related to our collections; it is a very organic cooperation, friendly and open. It has always been very strong, and it remains this way — nothing has changed and nothing will change. It [the relationship] does not depend on any political situation, it depends on the motivation of the two museums that understand that what they are doing: creating cultural bridges," Loshak explained.

If beauty is an enduring theme, it is also a universal one: across cultures, countries and art forms. "Everyone has their own Venus," began one anonymous comment in the exhibition visitors book. Looking at the paintings that have shaped the way we perceive beauty, this certainly rings true.

Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. 12 Ulitsa Volkhonka. Metro Kropotkinskaya. +7 (495) 697 9578. arts-museum.ru. The show will run until July 17.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.