Nina (not her real name) was desperate when she opened the box and placed her one-year-old son inside. Months earlier, her husband had left her, and now he was nowhere to be seen. She had no permanent job and minimal savings. And she had just been forced out of her apartment by aggressive debt collectors, who had thrown stones through her window and burned down her front door.

She had no choice. "I had to leave my son somewhere temporarily so I could get my life back on track," she says. "I looked for care homes, state facilities, anything but found nothing — then I came across baby boxes."

There are currently 19 baby box schemes functioning across 12 Russian regions. These incubator-type enclosures allow parents to leave an unwanted newborn, anonymously and without legal repercussions. The first schemes were introduced in 2011 by the charitable foundation Cradle of Hope, based in the central Russian region of Perm.

The process of depositing babies is designed to be simple and safe. The boxes themselves are located in medical facilities. The parent opens the box and leaves the baby inside. In 30 seconds, the box door is locked shut, and the staff inside receive a signal to take out the baby. Six months later, the child is put up for adoption, but before then its relatives can change their minds and take the baby back after undergoing a DNA test.

Nina, who was just 22 at the time, says she knew that she would be able to take her son back within six months, but was nonetheless very distressed by the process. "When I left him, I cried for a month non-stop," she says.

In and Out of Grace

Government isn't yet sure where it stands on the baby box scheme. Some regional authorities, for example, have sided with baby box advocates, agreeing that they save lives and help fight infanticide. Others have sided with their opponents who argue baby boxes encourage women to give up their children — a cardinal sin in today's Russia, which champions "traditional family values."

In some regions — like southern Krasnodar and Moscow — local authorities began running their own schemes. In others, programs were drowned by scrutiny and inspections.

The latest standoff played out in the Russian parliament. In December 2015, several senators from the Federation Council introduced a bill to the State Duma that sought to legitimize and fund the installation of baby boxes.

Three months later, with the bill yet to be debated, children's ombudsman Pavel Astakhov filed a request with the Duma that the bill be abolished. "There are no easy solutions, least of all containers for children to be dumped anonymously," Astakhov's press office told The Moscow Times. "Baby boxes do not deal with the root causes of the problem."

Babies in Dumpsters

"I don't understand where they get such arguments from," says Vadim Tyulpanov, one of the senators who put together the bill. "Astakhov claims that baby boxes encourage more women to abandon babies, but, in fact, they don't — in the past five years only 47 babies were left in such a way. Also, a woman can as easily give up her child in a hospital, right after she gives birth," he told The Moscow Times.

Meanwhile, "saving 47 lives speaks for itself," Tyulpanov says.

According to the lawmaker, "many regional governors want baby boxes," but are afraid to install them due to a lack of proper legal status. In the past few years, authorities introduced baby box schemes "at their own risk." Passing a bill would solve this problem, but it is likely deputies will be influenced by Astakhov's well-publicized intervention, he says.

Yelena Kotova, the founder of Cradle of Hope, agrees. "If baby boxes save just one little life, they are useful," she says. "Every day we receive horrendous reports: dead babies found in dumpsters, women arrested for stabbing their newborns to death, or suffocating them, or hiding them in their freezers," she says.

Russian newspapers have reported often on dead babies lately. On March 25, the corpse of a baby was found in a Moscow park, wrapped in a blanket and placed inside a shoebox. Several days before that, police discovered another tiny corpse — this time in a cemetery dumpster in the Ivanovo region.

Infanticide and Abandonment in Russia

In the same week, a Chelyabinsk woman was convicted for killing her newborn baby with scissors; a week previously, a couple were arrested in Nizhny Novgorod for drowning their newborn in a bathtub and dumping the corpse in a forest.

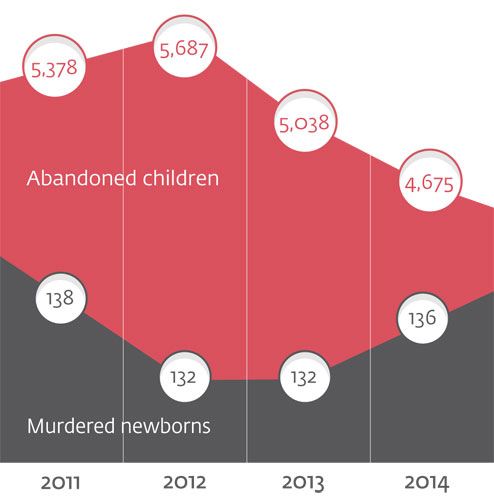

According to official statistics from Russian law enforcement, 538 newborns were murdered between 2011 and 2014.

Kotova has studied some of these cases. Most of the women who killed their own children were "not unusual," she says. "They were ordinary women like you and me, and some of them even had one or two other kids."

For Kotova, baby boxes work predominantly on two levels. Not only do they save children from death, they also offer a way to reunite babies with parents who have second thoughts. So far, her foundation has helped seven mothers reunite with their children.

One of her most recent cases involved a young Muslim woman who secretly gave birth and brought her newborn girl to a baby box, fearing retribution from her religious relatives. Two days later, the woman returned for her daughter.

"Can you imagine what would have happened if she had left the child, say, in an alleyway?" Kotova asks. "The baby box gave her a chance to sleep on it, to cry it out, share her secret with her aunt and change her mind. If she had left it elsewhere, the baby simply wouldn't have survived."

Finally, the baby box option gives young mothers the comfort of anonymity. Leaving a child in a hospital after giving birth is supposed to be anonymous, but in practice it isn't. Mothers are required to sign a document with their full name and address, stating that they are ready to give up parental rights.

Problems

Others believe the focus on baby boxes obscures the real issue. Often mental issues are at play, says Lyubov Yerofeyeva, a gynecologist, family planning expert and head of the Population and Development NGO. "They kill not because they don't know where they can leave their babies, they kill just because," Yerofeyeva told The Moscow Times.

Rather than trying to legalize baby boxes, authorities should concentrate on the prevention of unwanted pregnancies. "Create programs for preventing unwanted pregnancies, promote birth control and give it for free to the most vulnerable groups," Yerofeyeva says. "Authorities always like easy options, and baby boxes are exactly that."

Yerofeyeva says she is also concerned by the complete anonymity that baby boxes allow. "What if the baby that was put in a baby box was abducted? What if another crime was committed to this baby? There is no way of knowing," she says.

Indeed, in September 2015, an old woman from the southern city of Stavropol took her grandchild to a baby box without the parents knowing. The woman had decided it was too expensive for her daughter to raise yet another child.

Some volunteers wonder if the mothers themselves are in the right state of mind to make a decision to leave their babies in anonymous boxes. "There is always a bigger crisis behind the abandonment, and a baby box doesn't solve it," says Yelena Alshanskaya, head of the Volunteers to Help Orphans charity foundation. "A plastic box solves one aspect of a critical situation, but the difficulties that forced the woman to abandon her baby in the first place don't go away," she says.

Women who use baby boxes often make life-changing decisions on their own, without consulting psychologists and family planning specialists. "We know nothing about the woman. What if she is depressed? What if she hangs herself a month later?" Alshanskaya asks. "Instead of baby boxes, we should be concentrating on providing counseling for women who find themselves in trouble."

Emergency Exit

Alshanskaya cites the reports of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, which have repeatedly recommended abolishing baby boxes in the few European countries that have them — such as the Czech Republic, Latvia, Germany — and in Russia. Yerofeyeva echoes her statement: European countries are giving up this practice, she says, and putting more emphasis on the root problem, which is avoiding unwanted pregnancies.

But the Cradle of Hope's Kotova says people have misunderstood the role of baby boxes. "Of course they don't solve the main problem and I have no idea why everyone treats them like they should," she says. "It's an emergency exit, a fire escape for people who have fallen into the abyss."

Indeed, Kotova's foundation, based in the Perm region some 1,400 kilometers east of Moscow, has already helped regional authorities open a crisis center for women in need.

This is where Nina, desperate to improve her living conditions in Moscow, now lives. Less than a month after leaving her one-year-old child in a Moscow-region baby box, Nina decided to take him back, and she contacted Kotova.

"Yelena has been helping me like you wouldn't believe!" she says. "She gave me a job at the foundation, and we are about to receive permission for a DNA test in a couple of days."

Nina is happy about the prospect of reuniting with her son. "For women like me, who didn't know what to do in a difficult situation, baby boxes were a blessing," she says.

Contact the author at d.litvinova@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter at @dashalitvinovv

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.