The history of Russian rock music could have been very different without Joanna Stingray. As a 24-year-old California clubber, she spent a week in the Soviet Union in 1984 and fell in love with the Leningrad underground rock scene. Joanna was friends with rock musicians, recorded songs with them, shot their videos and brought them clothes and instruments from the West. Her video footage, capturing young icons of Russian rock like Viktor Tsoi, Sergei Kuryokhin, Timur Novikov and Boris Grebenshchikov, is rare evidence of the golden era of the Soviet underground.

Joanna now lives in Los Angeles with her daughter Madison. She has not visited Russia for 12 years. On March 7, the Leningrad Rock Club music venue celebrated its 35th anniversary. Joanna shares some of her memories below.

I had dreamt about visiting Russia since my adolescence. In 1984, my sister went to study in London and from there she had an opportunity to take an inexpensive trip to visit the Soviet Union for one week. She invited me to come along.

Moscow looked very much like Russia as it was presented in the West. It was terribly cold, everything was gray and not a single happy face.

When I arrived in Leningrad, I started looking for Boris [Grebenshchikov from Akvarium]. A close friend of my sister who was a Soviet emigrant had given me his phone number. Over the next three days, Boris and his friends showed me an entirely different Russia — here, people laughed, talked about everything, drank and played music. After those three days in Leningrad the only thing I could think about was how I could get back to the Soviet Union as soon as possible.

I first encountered the Leningrad Rock Club during my second visit, also in 1984. The atmosphere at the rock club was the same as at concerts in Los Angeles. A couple of months later, Boris took me to a Mashina Vremeni concert in Moscow. The difference between an official concert and the Rock Club concert was like night and day. At the Mashina Vremeni concert, everyone sat stiffly in their seats and clapped between songs as if on cue. When a guitarist broke a guitar string in the middle of the performance, the concert stopped for 10 minutes while the guitarist replaced the string in total silence. Boris explained that the musicians were not allowed to do anything that did not conform to the approved program for the performance.

My first encounter with the KGB occurred during that first visit to the Rock Club. After the concert I was planning to go backstage to Boris. I happened to turn and got an unpleasant look from a strange man who immediately tried to blend in with the crowd leaving the hall. As soon as I exited, two people grabbed me and took me downstairs to some room. They were dressed in ordinary clothing without any identifying insignia. I was worried. They started speaking to me in Russian. I answered that I didn't understand a word of Russian. They continued asking me questions in Russian. I again told them that I am a U.S. citizen and that they should call the U.S. consul. They looked flabbergasted.

When I left the Rock Club, a young woman approached and said that now KGB agents were following me, that I needed to lose them and only then go to the after-concert party. For half an hour I wandered around Leningrad and some man really was following me. It was really obvious, like in spy comedies. When I no longer saw him anymore, I went to the party at an apartment on Nevsky Prospekt and Boris introduced me to Viktor Tsoi and Yury Kasparyan from Kino.

Many of the rockers in the Rock Club were under KGB surveillance. The rockers reacted in different way: some would meet with the KGB, others hid from them, and still others would talk back to them. Boris met with the KGB and told them that he was only a musician and played music. He told me later that they asked him a lot of questions about me, which was really unnerving.

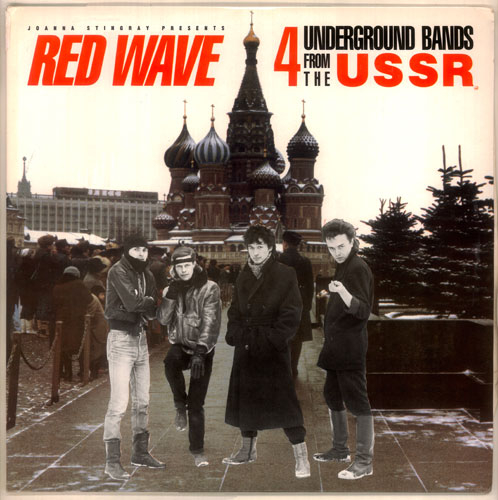

"Red Wave" was the first release of Soviet rock music in the United States. Recordings by four Leningrad bands were smuggled out by Joanna Stingray. It was released by Bug Time Records on June 27, 1986.

Boris once told me that I was like Santa Claus for Kino and the other friends. When I promoted Russian rock in the U.S., I met with different companies and showed them pictures of Akvarium, Kino, Alisa and Stranniye Igry. Everyone was impressed with how cool the Soviet rockers looked. Many gave me gifts to bring them. For example, music magazines gave me T-shirts with their logos after we did a series of interviews devoted to the release of the "Red Wave" album.

I took more than just T-shirts there. Somewhere I have an old photo where I'm preparing for my next trip to the Soviet Union. I have two metal cases with base guitars, a huge trunk with keyboards — a whole music store. I took lots of stuff to Leningrad and the musicians really appreciated it.

I was scheduled to appear with Akvarium for my first performance. But not long before the concert Boris told me that the KGB had called and warned that they would halt the concert if I went onstage. When Viktor Tsoi learned about it, he said I could go onstage with Kino and that he didn't care whether they canceled the concert. And that's how I first performed in Russia.

The "Red Wave" album, designed to showcase Russian rock music in the U.S., included four groups — Akvarium, Kino, Alisa and Stranniye Igry. It wasn't easy getting the recordings for "Red Wave" out of the country. The tracks were recorded on reel-to-reel tapes that were outdated, large and unwieldy.

I hid the paper with the lyrics under the lining of my boots and the tapes in a secret pocket of my jacket. I was smuggling the music out as if I were a drug courier. The safest route was from Leningrad to Finland because they didn't search people as thoroughly in the Leningrad airport as in Moscow.

The album was received incredibly well in America. It had never occurred to anyone that Russia had rock music and rockers like in the rest of the world. It was a different view of Russia.

When I returned to the Soviet Union, I first went to the VAAP (Soviet Copyright Agency). They gave me a long lecture and a paper to sign saying that I had smuggled the recordings out without the musicians' knowledge.

I quickly agreed to sign it, gave VAAP the royalty fee and thought that the matter was settled. I returned to the States riding on a cloud and prepared for my wedding to Yury Kasparyan. But after that meeting they banned me from entering the Soviet Union for six months, with the result that I missed my own wedding. The only consolation for me was the funny pictures that Viktor Tsoi sent me regularly along with encouraging messages: "Joanna, don't worry. We love you and miss you. We're waiting for you."

I left Russia in 1996. It's amazing that my music and I still have loyal Russian fans. Since leaving, I have returned to Russia just once, in 2004, with my daughter Madison. That was 20 years after my first visit. Madi and I appeared onstage and sang "Pust vsegda budet solntse" ("May There Always Be Sunshine"). I dream of going back.

This story was contributed by Colta.ru, an independent cultural website. The Moscow Times thanks them for their cooperation.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.