Boris Nemtsov never believed he would be murdered. Of course, he understood he might be harassed in one way or another. He knew the authorities might have plans to send him to prison. He felt this even more keenly after they called him in for questioning and searched his apartment. But he never for one minute imagined that someone could shoot him in the back.

Nemtsov occasionally recalled the time when then-FSB head and now President Vladimir Putin came to his government office asking for help in obtaining apartments for intelligence officers. Those FSB employees feel pretty high and mighty these days, but back in the 1990s they were just mid-level functionaries at best. Nemtsov pulled some strings for Putin and genuinely believed that the FSB chief would always remember the favor.

"I was deputy prime minister, Putin's boss," Nemtsov used to say. "They can't kill me."

Putin himself was ambiguous when he met with journalists in December 2015. "Nemtsov embarked on a path of political struggle, but that does not necessarily mean that he had to be killed," he said. It was a statement both cynical in form and monstrous in its message.

Of course, Nemtsov realized that he was running a risk by working for the opposition. But he was never afraid. He walked around Moscow without bodyguards, carried a metro pass in his wallet and was not averse to taking the subway if his car got stuck traffic.

People greeted him warmly wherever he went; they'd ask for autographs and to take pictures with him. He loved speaking with people and could easily find a common language with everyone — even with his critics and opponents.

Occasionally someone would try to provoke him by throwing food at him or even physically attacking him. But Nemtsov was a strong guy and was always ready to repulse an attacker. I remember an instance in Yaroslavl when a man tried to hit Nemtsov, but ended up with a fist in the face for his trouble.

I don't think Nemtsov ever really accepted the possibility of his own death. He thought he would live forever. At 55, he was an accomplished runner, could do pull-ups with ease and was proud of his physique. He was an amazingly cheerful person. It never crossed his mind that everything might suddenly end. I never met anyone with such a love for life, anyone who could so easily infect others with his optimism.

And now already one year has passed since his murder.

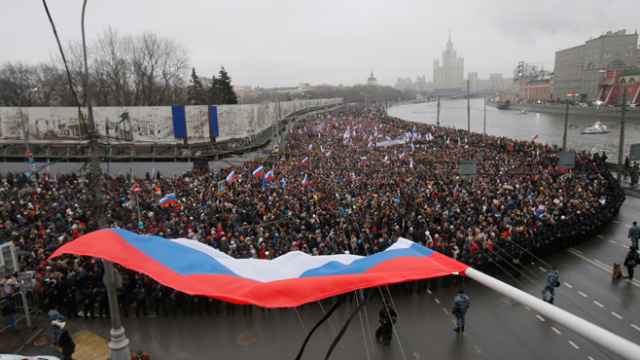

This was essentially an act of terrorism, a high-profile assassination, intended to intimidate others. I am certain that he was killed in order to silence critics of the Kremlin, and to compel them to leave Russia. And many people did exactly that: They got scared and left the country. But the murder also had the reverse effect, one that whoever ordered the murder had not anticipated. Many people who were shocked by Nemtsov's murder joined the protest movement and became activists for the opposition.

The killing also demonstrated that the siloviki's hands are tied when it comes to investigating political assassinations. During the initial stage, investigators managed to apprehend the trigger man and put together a criminal case with strong evidence showing that he was an officer of the Chechen battalion "Sever." But the moment it became clear that the trail led back to Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov and other government officials, the investigation stopped.

It is now abundantly clear that the people behind Nemtsov's murder will escape accountability — at least until a new team moves into the Kremlin.

All of this raises serious concerns for the future of Russia. After all, if people with close Kremlin ties can carry out such a brazen murder with total impunity, it means they essentially have carte blanche to do what they want.

And that means that the federal authorities and the siloviki have through passivity and inaction set the stage for yet more political assassinations.

Ilya Yashin is a politician, activist and friend of Boris Nemtsov.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.