Tatyana, a good-looking blonde, leans across the table. "You fancy sticking around for a drink?" she asks with a naughty smile. The subject of her advances, a British Moscow Times business reporter, blushes with embarrassment.

It is Saturday evening and we are nearing the end of a foreign-friendly speed dating session in a central Moscow restaurant. Roughly twenty men and women have paid 1,500 rubles ($19) to meet a potential new love interest.

Even though only two expats are in attendance, organizers clearly think the "foreign" tag is a crowd puller. Russia is entering its second year of crisis, widening the lifestyle gap between Westerners and Russians.

The economic slump has had an impact on the supply side too, as foreigners leave the capital in droves.

All of this should be good news for expats' love lives. But the fascination with foreignness is, it appears, skin deep. Moscow today, with its hip cafes, shiny business centers and fashionable retail stores, is no longer the Moscow of the '90s, when girls fantasized about being whisked away by a foreign prince in Levi's.

American Joy

When Russia plunged into chaos following the collapse of the Soviet Union, many of its citizens looked for a reliable way out. Naturally, foreigners were viewed as a bridge to the more developed and "civilized" West.

The popular rock group Kombinatsiya summed up in endearing, if flawed, English what was most on Russian girls' minds:

"American boy, American joy.

American boy for always time.

I will go home with you.

Moscow bye-bye!"

Russian women gained a name for going weak in the knees for anyone from the West. That reputation persists today, and it is not wholly without cause. Most male expats say that their nationality can still have a positive impact on girls.

"You can just speak English and heads will turn," said Sean, 26, an English language teacher. Russian women are also more forward, he says: "You can just be talking to someone and some beautiful girl will come up to you with a chat-up line. Back at home, the guy would have to have to make the first move."

Not every Russian woman has access to expat hangout spots, though, giving rise to a booming business of dating agencies that specialize in foreign men.

Type the Russian words for "get married" or "meet" and "foreigner" into Yandex — the Russian equivalent for Google — and a door opens. This is a world of dating agencies, psychologists, therapists, etiquette training and self-help courses, all geared towards the question of where to meet and how to keep foreign lovers.

Many of the agencies also offer English language courses and translators to facilitate online communication. In many cases, the linguistic efforts are rewarded. Forums are full of the accounts of Russian women thanking their coaches for a "happy end" — engagement or marriage to a foreigner.

"Thanks to you and your website I got married yesterday!" says an excited girl called Oksana. She describes her friendship with an American man: "I was once too afraid to believe in fairy tales."

Sixteen percent of all marriages registered in Moscow in the first ten months of 2015, were mixed, according to data from the state registry office. The most popular source countries were Ukraine, Turkey, Moldova and CIS countries, followed by Germany, Afghanistan and Israel. Britain and the United States also featured on the list.

Galina Ponomaryova, 63, has been a dating coach for 15 years. Her self-help book promises to hand women the key to "joint travel, candlelight dinners, a home in Europe" and a "comfortable life" in 90 days. Ponomaryova says that the industry has gone through trends. Initially, women were hoping to find a partner from the United States, then Britain. Today, European countries and Turkey are more in vogue.

"Who the most desirable foreigners are, depends on fashion. Its all between the ears," she said.

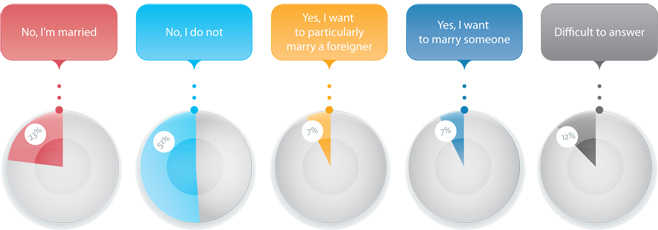

Poll asks: Do you want to marry a foreign man?

Generation Gap

Decades after the Soviet collapse, the "American Boy" fantasy is starting to fade. Following an economic boom during Putin's first term, living standards have improved and many of the perks of living in the West are now on offer in Moscow too.

In a poll conducted in 2009 by Superjob.ru, one in four women aged 55 or older said she wanted a foreign husband. In the age group ten years below that, only 9 percent wanted a foreigner. And the number continued to drop to 6 percent among those aged 25 or younger.

As the economic motivation to search for a partner abroad has weakened, most of the reasons for looking beyond Russia's borders are cultural, says dating coach and English teacher Svetlana Tolstykh, 40.

Tolstykh, whose agency "Here I Am" helps Russian women establish relationships with European men, said most of her clients were "mature" women who had already gone through a divorce or had been disappointed by their relationships with their fellow countrymen.

"There's an idea that foreign men will be different [from Russian men]," she said. European men have a reputation for being more independent and better planners. She said they are also more emancipated — willing to take on household chores and take up an active role in raising children — and that they were softer in their communication.

But among younger Russian women, who did not experience life under the Soviet Union and are too young to be scarred by past experiences, foreign men have less cachet.

During the speed dating session, most women told the Moscow Times reporter that dating a Russian man would be easier and cause less friction. Tolstykh said that more travel experience meant the younger generation of Russian women no longer viewed foreigners through "rose-colored glasses."

Terror stories about women who have moved abroad have helped to paint a less rosy picture of mixed marriages. The popular state television program "Let Them Talk" recently covered in detail a story of a Russian woman who moved to Norway and was then beaten to death by her Norwegian husband.

As relations between Russia and the West have soured over the Ukraine crisis, the image of Europe as a beacon of stability has also suffered, with the Greek economic troubles and Syrian migrant crisis receiving broad coverage.

"Who wants to go to Europe anyway, with all the chaos that's going on there?" said Tatyana at the speed dating session.

A floundering ruble is not likely to be enough to change that trend, suggested dating coach Ponomaryova. Indeed, in her view, the economic crisis has made Moscow women want to stick with the familiar.

"It's better to wed one of your own, than an overseas prince. Life is not as scary," said one respondent in a poll conducted by the Superjob.ru website.

Dating coach Tolstykh expects that the niche of women expressly looking for foreigners will become smaller as a new generation of Russian men adopt more emancipated views on relationships.

Her own daughter returned to Moscow at age 20 after several years in Ireland, only to get married to a local Muscovite.

Tolstykh predicted that in several decades the services offered by dating business like hers would have to be renamed from "find a foreign husband" to "find love" — in the footsteps of their Western counterparts.

"In the end it's all about love," said Tolstykh. "Of course Russian women want their lives to be set up comfortably but to be in a loveless relationship … You don't need to leave Russia for that," she said.

Contact the author at e.hartog@imedia.ru and p.hobson@imedia.ru. Follow the authors on Twitter: @EvaHartog and @phobson15.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.