President Vladimir Putin chose an unfortunate time to trumpet the "additional opportunities" for Russian companies arising from a weaker ruble.

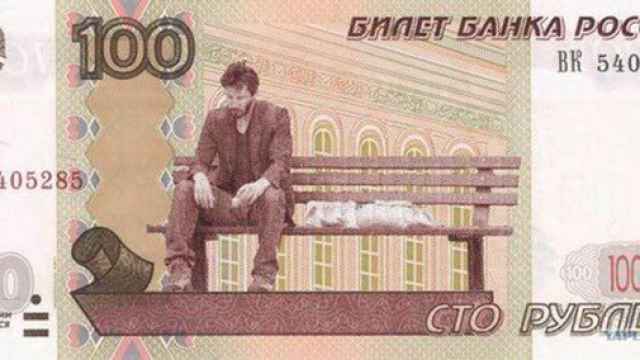

As he spoke to delegates at a business forum on Jan. 20, the Russian currency was gyrating wildly. The next day it plummeted to its lowest level in recent history, losing 4 percent against the U.S. dollar and then regaining it in the space of a few hours. At around 76 rubles to the greenback, the Russian currency is 4 percent weaker than at the start of January, and its value has halved in less than two years.

The dramatic devaluation is usually seen as a calamity. Driven by a sharp fall in oil prices, it has massively raised the cost of anything imported from overseas, fueling inflation and leaving most Russians significantly worse off.

In theory, Putin could be right that a weak ruble also provides economic upsides. A weaker currency should make Russian goods and services vastly more competitive both at home and abroad. This could electrify sectors of the Russian economy. But a lack of cash for investment and uncertainty about the country's future are getting in the way.

Filling Market Gaps

The weaker ruble has transformed Russia's trade with the rest of the world. Russian imports fell by $107 billion, or 37.7 percent, over January-November last year compared with the same period in 2014, according to data from the Rosstat state statistics service.

A drop in imports should be good news for Russian companies, allowing them to step into vacating markets. But with real wages shrinking, Russians are consuming less. Russian money to invest in new production capacity is in short supply due to the recession and high interest rates. And Western financial sanctions on Russia over its actions in Ukraine saw foreign direct investment plummet 92 percent in 2015, according to UN statistics.

Much of the equipment needed to increase capacity has to be bought from overseas at prohibitively high prices. And the ruble's extreme volatility "makes it difficult to take decisions," said Dmitry Polevoi, chief economist at ING bank.

Food producers have extra incentive to increase production following Russia's retaliatory ban on imports of many Western products, and output of foods including meat and cheese grew last year. But the grim economic outlook still weighs. A U.S. businessman, who requested anonymity, said demand had increased, but he was only cautiously expanding his baked goods company, "not knowing where things are going to go."

The weak ruble isn't helping yet, said Polevoi. Potential benefits would appear only "in the medium to long term," he added.

Exports

Russia should be able to profit from exports that have become cheaper for foreign markets — such as weapons, rockets, cars, natural resources and grain. But cashing in quickly has proved difficult.

Take the car market. The price of a Russian-made Lada Granta sedan in dealerships starts from around 350,000 rubles. In early 2014, that was $10,000. Now, it is $4,500 — a hyper-competitive price for nearby Europe.

But cars cannot be rolled over the border immediately, said Vladimir Bespalov, an analyst at VTB Capital, a Russian bank. Time and investment would be needed to locate local partners and ramp up distribution and promotion, but that plan would require 2-3 years to complete, he said, during which the ruble could easily strengthen and wipe out the Lada's price advantage.

Similarly, cheaper labor has reduced costs for producers of Russian commodities such as oil, grains and metals. But new investment is strangled by sanctions.

Russia's most developed export market — former Soviet states — is also in the economic doldrums. Oil producers Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan have suffered from the falling price of crude. Countries like Belarus and Kyrgyzstan are closely tied to Russia's economy and have slumped with it. Sanctions have effectively cut off Ukraine.

Russian arms exports — worth around $15 billion in 2014 — have been hampered by Western embargoes. But potential buyers like Venezuela and Iran have also been hamstrung by low oil prices and are no longer able to splurge on weaponry.

In any case, "the export of arms is determined primarily by political factors" rather than cost of production, said Mikhail Barabanov, an analyst at the Center for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies.

Tourism

The real quick beneficiary of the weaker ruble has been tourism. Companies in the tourism industry have seen revenues increase by 30 percent over the past 18 months, said Dmitry Gorin, vice president of the Russian Association of Tour Operators.

Russia has become fantastically cheap for foreigners. Almost 20 percent more of whom visited Russia in 2015 than in 2014 — driven by an increase in visitors from China, Gorin said.

Meanwhile, more Russians are staying home. Those holidaying abroad tumbled by one-third in 2015 and 7 million fewer people bought package tours. Still fewer Russians will likely holiday abroad this year. Russian authorities have restricted sales of tours to Turkey and Egypt — which hosted half of all Russian tourists — and not everyone can afford to visit popular but increasingly expensive destinations in Mediterranean countries or Thailand.

But while the growth is a boon to the local tourism industry, some Russians might be less pleased.

A quarter of Russians polled after holidaying at in Russia say they did not like the experience, according to Gorin. Rather than switch to domestic travel, many prefer to wait and save up on weak rubles to go abroad, he added.

Contact the author at p.hobson@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter: @peterhobson15

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.