China, the world's most populous country, might have slipped through its fingers, but with Russia Netflix in January pocketed the largest country by landmass and the promise of tapping into a booming online market.

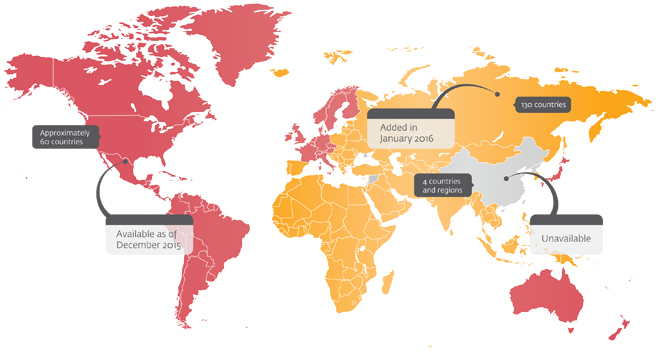

Netflix's move into Russia, along with 129 other countries, was heralded by its CEO as the "birth of a global TV network."

The streaming giant's formula of offering subscribers online access to box office hit films and series has already taken the United States and much of Europe by storm, where it has more than 70 million users. Its core strategy is simple: First, offer people content they want to watch. Then, make them pay to watch it online.

Netflix's prospects in Russia are promising: The country has a culture of television watching and boasts one of the fastest growing Internet audiences in the world.

Disappointment

The announcement of the Russia launch was widely met with enthusiasm both among locals and foreigners living in Russia. One American expat on Twitter compared it to "eating flatbread pizza after fasting for a week."

But the euphoria was short-lived and comments on forums and Russian social media websites quickly turned sour. As in many other countries, the interface of the Russian Netflix website — its buttons, directory and messages — are all in English. The service is "uncomfortable" for Russians, said television critic and Rossiiskaya Gazeta journalist Susanna Alperina.

More importantly, many of the series available do not offer Russian-language subtitles or dubbing. Even for tech-savvy youth, the language barrier is a major obstacle likely to turn away many of Russia's 84 million Internet users.

Netflix's practice of having separate licensing agreements in every country also means it offers less content on the Russian website than on its U.S. counterpart. Whereas the U.S. version has roughly 5,700 movies and television series, the Russian Netflix only offers around 720, the Unofficial Netflix Online Global Search website shows.

And then there's the price tag. A monthly Netflix subscription will cost Russians at least 8 euros, or 660 rubles — more than the average Internet bill. It is pricier than Netflix's main Russian rival, ivi.ru, which costs 399 rubles a month and offers free content.

With the ruble devaluation and more economic turmoil expected this year, the cost could discourage subscribers.

In fact, the only Russia-specific adaptation Netflix appears to have made is to block access to users in Crimea — the peninsula annexed by Russia in March 2014 — in compliance with U.S. regulations restricting American business there.

Netflix is selling Russians less content, much of it in a language they don't speak and at a prohibitive price. Hardly a great buy, according to many disappointed Russian fans. "No one wants Netflix the way it is now," programmer Dmitry Alexeyev, 25, said.

Netflix did not respond to several requests for comment from the Moscow Times.

One Size Fits All?

Part of the reason is structural. The latest global push built on Netflix's xisting network of around 60 countries, converting it into a truly global player.

With such an extensive market, its strategy is to offer users across the world the same content, rather than narrowly catering to national specificities.

" Consumers around the world — from Singapore to St. Petersburg, from San Fransisco to Sao Paolo — will be able to enjoy television shows simultaneously," Netflix CEO Reed Hastings said in January.

But it is too early for Neflix's Russian rivals to breathe a sigh of relief, media experts said. Russian users report that since Netflix's launch, more films and series have been equipped with Russian-language subtitles. And in comments to Sputnik news agency, Netflix said it could add Russian language support "over time."

Netflix also plans to increase its in-house content, such as the hit series House of Cards, which it can globally promote on its own platform. That spells trouble for other companies on Russia's fledgling video streaming market.

Fierce Competition

There were about 20 players on Russia's on-demand streaming market, which was worth 2.6 billion rubles ($34 million) in 2014. Half of the market share was held by websites ivi.ru, with 28 percent, and Okko, with 22 percent, according to TMT Consulting data. Players Tvigle and Megogo had a 9 percent market share.

Much of their success has come on the back of Russian-language versions of foreign box-office hits, including House of Cards — which, incidentally, features a character based on Russian President Vladimir Putin.

But Netflix could also provide competitors with an incentive to innovate. Inspired by Netflix's business model, ivi.ru earlier announced plans to produce its own in-house content.

The arrival of Netflix will most likely consolidate Russia's legal streaming market into only a handful of strong players, the head of film distribution "Volga," Sergei Spiridonov, told the Rossiiskaya Gazeta newspaper.

But beating their U.S. frontrunner to the game will prove a tough challenge for Russian companies, which are relatively unexperienced, Alperina said. "They are still probing the future," she said. "In the United States, Netflix broke the existing model [of watching television]. There is a possibility the same will happen in Russia," she said.

By 2020, the streaming market is expected to grow to 9.5 billion rubles ($125 million), TMT Consulting data shows, helped by an expected crackdown on illegal torrent websites and video sharing on social media — both hugely popular in Russia.

Netflix does not offer national breakdowns of targets, but as it increases its trendy in-house content, it could drag that growing audience into its net. Most young Russians already prefer U.S. series over Russian content, Alperina said.

"The older generation of Russians doesn't care whether House of Cards is on. The youth can't live without it," she said.

Contact the author at e.hartog@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.