Simon Mraz, Austrian cultural attache, director of the Austrian Cultural Forum and tireless promoter of the rising stars of Russian art, compares his adopted country to a treasure box.

Six years after moving to Moscow as a freshly minted diplomat — armed with an art history degree and several years' experience at an auction house — Mraz seems to find new talent springing from Russian soil at every turn. And unlike most foreign visitors and diplomats, he doesn't limit his search to the cultural capitals of Moscow and St. Petersburg.

His travels have now taken him beyond the Arctic circle, into the mountains of the North Caucasus, and into the twilight zones of the once-mighty Soviet industrial cities, lovingly documented by the latest exhibit he curated, "Nadezhda — The Hope Principle."

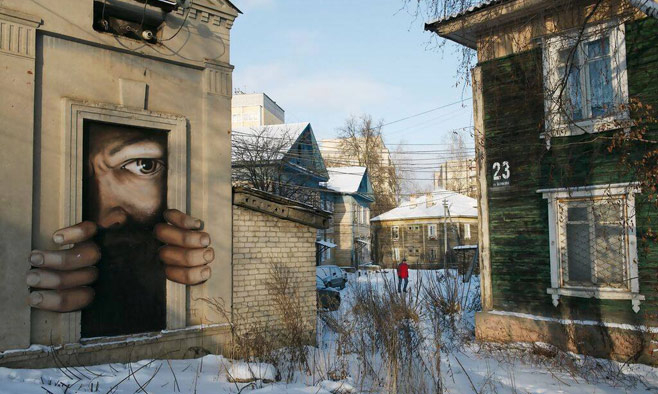

The works and especially photographs in "The Hope Principle" show were startling in their subjects and unexpected beauty.

Expanding Russia's Art Map

First shown in November in Moscow's Trekhgornaya Manufaktura, one of the capital's industrial-spaces-turned-creative-hubs, the exhibition invited 25 Russian, European and American artists to set forth into seven former "factory cities," whose giant plants were supposed to propel the Soviet Union into its promised "bright future."

Mraz's day job as cultural emissary provided a network of Western European contacts, which helped assemble what art critics deemed an impressive cast of artists: Austria's Sonia Leimer and Andreas Fogarasi, Denmark's Tue Greenfort, Germany's Fabian Bechtle and Leon Eisermann, America's LaToya Ruby Frazier.

He secured the backing of the Dutch and Danish embassies and the Goethe Institute, as well as 16 institutional sponsors — not a mean feat in the bleak economic and political climate.

But the joy of it for him seems to be bringing together Russia's young creative artists, who form nearly half of the line-up. Russian photographers were called on to document these sometimes surreal and sometimes melancholy settings.

"The name came from a photograph by Elena Chernyshova, showing the sign by the entrance to Norilsk's Nadezhda [Hope] metallurgical plant," he explains, holding out the picture: red, angular Cyrillic letters glistening against the snow, as the plant's many chimneys puff out clouds of smoke into the darkening sky.

"The site is off limits to foreigners; I couldn't even visit. But as soon as I saw that sign, I knew what the show's guiding idea would be."

The exhibition, portraying the remote outposts of Magnitogorsk and Norilsk as well as urban centers Nizhny Novgorod and Yekaterinburg, was meant to show their decline — and sometimes, rebirth — without sugar-coating, but with a view to highlighting the possibilities their future might still hold.

For Mraz, "Nadezhda" referred to hopes for reversal of the cities' fortunes, for the embrace of art as a valid means of self-expression by local communities; but also for fruitful dialogue between international artists and the sometimes staunchly conservative Russian authorities.

"These cities and their history are an integral part not just of Russian culture, but also of European and world heritage," he says. "And sometimes, to put a place back on the map, it is better to send an artist than an economist or a cartographer. Artists have no hidden agenda, they are able to look around with fresh eyes."

Mraz's own collection of art includes works by young Russian artists living and working in Russia today. Mraz says they share some of the same experience of Moscow and the country.

Embracing History

Mraz is no stranger to finding beauty in what many would consider the menacing specters of Russia's recent history. His 2013 project "Lenin Breaks Ice" transformed the old nuclear-powered Lenin icebreaker, stationed in the far northern city of Murmansk, into a unique exhibition space, with Russian and Austrian artists teaming up to show a variety of bold, sometimes provocative works and bring out the ship's original aesthetic appeal.

To the curator's delight, some local authorities are taking note — which, for him, seems to translate into more travel plans. Last week saw him tour the autonomous North Caucasus republic of Karachayevo-Cherkessia at the invitation of its newly appointed culture minister, hoping to find inspiration in a new corner of his second homeland.

"It's fascinating — a true crossroads of cultures," he says. "The ethnic diversity, the millennia-old churches, unique local Muslim traditions, the Soviet legacy."

He adds that he is not yet sure whether this fascination will develop into a new project — but he has already had the chance to meet some Cherkessian artists.

However, most of the time, he does not need to venture far to nurture his passion. His own flat in Moscow's iconic House on the Embankment, a 1930s residential block which was once home to Stalin's daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva, is something of a private gallery, where Moscow's culture vultures often come to meet.

"The sense of history in this place is incredible," he underlines.

According to the architectural photographer Yuri Palmin, who worked with Mraz on the "Nadezhda" project, the gatherings in his apartment bring to mind "the unofficial exhibitions held in private flats in 1980s Moscow — except (...) it's not about politics or censorship. It's a meeting space."

His next personal project is likely to follow the "Nadezhda" template. With the hundredth anniversary of the October Revolution coming up, he is eager to invite Russian and foreign artists to explore its legacy.

"First of all, we need to find an angle," he says. "Something original, something interesting. That's what I'm working on now."

When asked about his future plans, he says he does not want to plan years ahead.

"But I am not ready to leave Russia just yet," he adds.

In 2014 Mraz gave artist Andrei Kuzkin the keys to his apartment and asked him to paint. The result was a painted room, "Good Perspectives."

Building Bridges

Instead, his responsibilities keep multiplying. He has now been elected as President of EUNIC, the European Union National Institutes for Culture — a network uniting several foreign missions including Germany's Goethe Institute, the British Council, and the Alliance Francaise.

"My flat overlooks the Kremlin, and I have always thought it's funny — two Presidents eyeing each other," he laughs. "I don't do it for the title, it's not what I'm interested in. But partnering with other countries has allowed us to offer Russian artists some exciting possibilities."

One of the opportunities is a curating internship for young Russian art professionals in cooperation with Austrian, French and British contemporary art galleries. The annual competition, set to enter its fifth year in 2016, sends three winning curators to intern for several months at an institution of their choice. Mraz is eager to give them a range of options, roping more EU members into the project.

"The Poles are now eager to join, as are the Netherlands," he says.

He says he would like his work to foster dialogue — between Russian artists and their foreign counterparts as well as between artists and local communities and authorities.

"There is growing interest in art in Russia, but no widespread conviction that art is a crucial element of social life — of public discourse — so far," he reflects.

"I would like to help change that."

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.