Immediately following the harrowing terrorist attacks in Paris on Nov. 13, Russian pro-Kremlin media adjusted their rhetoric, abandoning their previous anti-Western and anti-U.S. vitriol even before the Kremlin spoke of a broad military alliance.

"A listener called Komsomolskaya Pravda radio station … and said that Americans are not our enemies, that it is politicians and officials who poisoned the well, but people feel good [about Americans]. … The presenter is also very friendly, and the whole program is devoted to [explaining that] Americans are not the enemies," Andrei Arkhangelsky, culture editor at the prominent Ogoniok weekly magazine, wrote on his Facebook page on Nov. 16. The post received thousands of likes and hundreds of shares.

Listening to the radio and monitoring the official political line has been Arkhangelsky's hobby since 2014. He tunes into Moscow FM stations daily, untangling the web of propaganda and describing its development on his Facebook page and in columns for the independent Slon news website.

FM stations are always first to pick up on trends. "Radio — no matter how strongly pro-Kremlin it is — is about live broadcast. It's about spontaneous reactions, naturalness, directness, emotions," he told The Moscow Times.

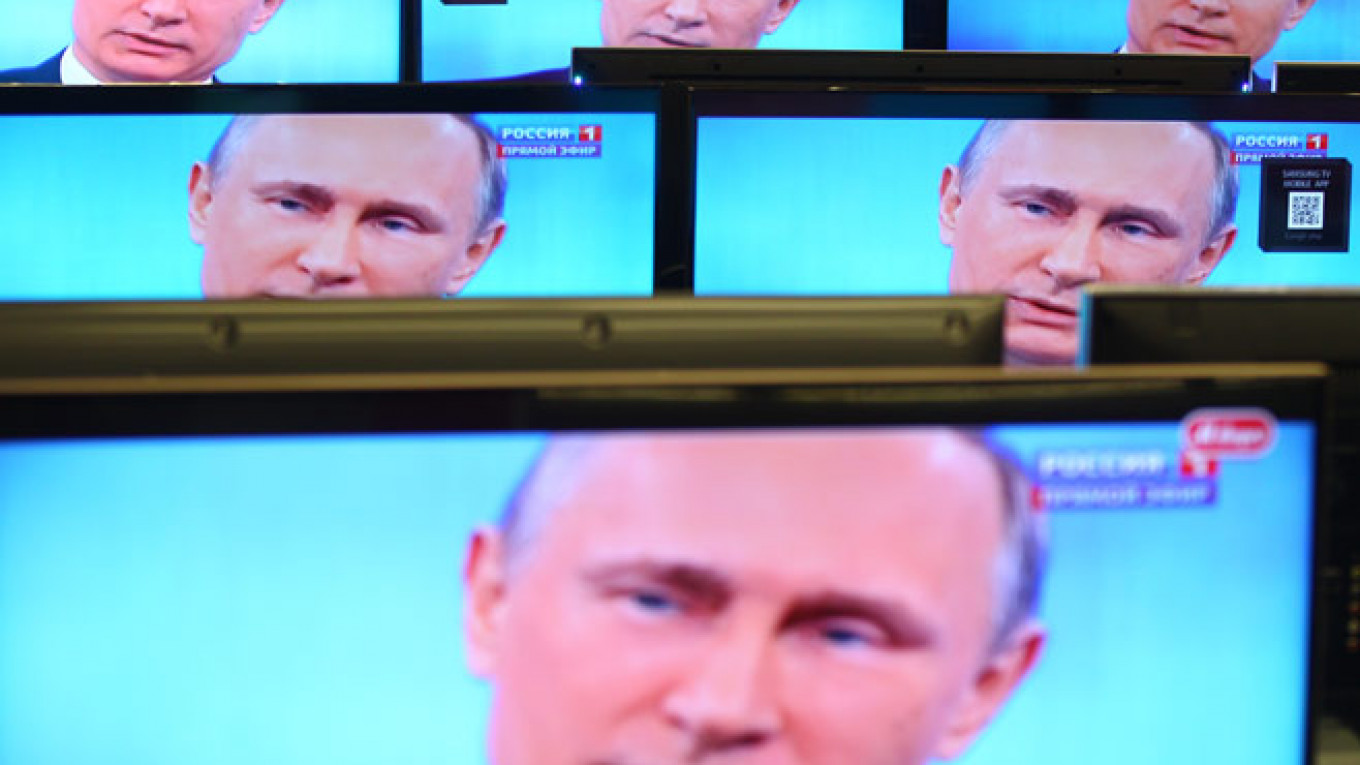

The Russian political and social agenda has become integrally linked with the chorus of television channels, newspapers, radio stations and social media commentators. While the propaganda industry requires governmental expenditure, resources and management, the Russian government requires propaganda for subsistence — it no longer simply influences public opinion but cannot be extricated from the national narrative.

Its expanding influence has provoked resistance from journalists, who explore and expose exaggerations, manipulations and blunt lies that fill the air on every relatively important subject. They do this as a hobby, separate from their regular jobs in prominent news outlets.

Public activism in Russia comes in waves, the early 2010s were the time of election observers and street politicians — and now television commentators and media observers have taken up their work.

To Understand Society through Radio Language

Andrei Arkhangelsky, 41

Culture editor for the Ogonyok weekly magazine. Began listening to radio stations — such as Ekho Moskvy, Business FM, Vesti, Russian News Service and Govorit Moskva — and writing about them in 2014. Is interested in the media language and journalist psychology.

Arkhangelsky, 41, has been listening to Russian radio for almost a year — stations such as Ekho Moskvy, Business FM, Vesti, Russian News Service and Govorit Moskva.

His columns and Facebook page examine how shades of radio language differ in various situations. "I'm very much interested in the media language, I study it as a cultural phenomenon. This language … draws a portrait of society," he said.

The tone of pro-Kremlin radio stations has changed significantly in the past couple years, he said. Even a year ago some stations could afford talking about opposition firebrand Alexei Navalny, for example, and give his lawyers airtime, but after things started crumbling in Ukraine, the tune changed into a simplistic opposition of "good guys" versus "enemies."

Meanwhile, there is no solid ground under current propaganda, he believes — it is all based on the idea of supporting and justifying anything the authorities do. "Current propaganda changes enemies almost every month. And listeners change their point of view as easily — I've observed it on numerous occasions," Arkhangelsky said.

His daily and thorough Facebook observations show that the first time Western countries were excluded from the media's list of enemies was on the eve of Russia launching air strikes in Syria in late September.

"Today, the airwaves of state radio stations had a year's worth of good and neutral [information about] America. This amount of positive information about the United States in one day can be called an anomaly," Arkhangelsky wrote on Facebook on Sept. 29, the day before Russia began its air campaign alongside the international coalition headed by the United States.

A week later Arkhangelsky had concluded that there was no solid official agenda thus far, and state media remained divided between the opposing narratives.

"The official agenda is stuck between 'America 1' and 'America 2' — between the all-time evil and the insecure partner. It's a strange, hesitating tone, and it's not clear which [narrative] will dominate. The propaganda is at a crossroads, it is still deciding how to talk about America," he wrote on Oct. 7.

According to Arkhangelsky — who said he was also very much interested in journalistic psychology — those who engage in the crusades that state media launch are ordinary people. "Geopolitics are a lot like childhood, when you feel on top of the world and there's no need for compromises," he said.

"The past 25 years haven't changed those 40-50 years old people — they just decided not to grow up. And those who are 20-25 now … were looking for something to believe in, and for them the Soviet Union became that something — a dream of a lost paradise, the time when 'everyone was afraid and respected us,'" Arkhangelsky added.

To Immunize the Audience

Alexei Kovalyov, 34

Journalist, translator. Used to work for the state-owned RIA Novosti news agency, left it shortly after it was liquidated in 2013. Started a blog that soon turned into the Noodleremover web project with more than 200,000 monthly visits.

"Nowadays production of false information [in the media] in Russia is almost an industry. It's not a case of casual inaccuracies or distorted perceptions, it's a deliberate process of creating fakes, and it's only gaining speed," said Alexei Kovalyov, whose website devoted to exposing lies and inaccuracies in pro-Kremlin reports has recently recorded 211,000 visits a month.

Kovalyov, 34, launched NoodleRemover.news — its name originates from a Russian idiom "to put noodles over one's ears," meaning to lie — in early October and started regularly exposing state-owned and pro-Kremlin media for manipulating their readers.

He himself used to work at a state-owned media outlet — the RIA Novosti news agency — but was dismissed, as were many other agency employees, following its liquidation at the end of 2013, when Rossiya Segodnya was launched in its stead under the rule of West-bashing television host Dmitry Kiselyov and Margarita Simonyan, the editor-in-chief of RT.

In the spring of 2014, as Simonyan's team began work in earnest, Kovalyov noticed that the agency changed its tone, embracing RT's manner of reportage.

According to Kovalyov, RT and RIA Novosti used similar know-hows, publishing stories with headlines like "96 percent of readers of an American newspaper voted for [Russian President Vladimir] Putin" — a claim based on an online poll on a small website where most voters were Russians — and citing experts that were not experts.

"For example, there was this expert on fighting terrorism, Scott Bennett, that both RT and Sputnik (RIA Novosti's project targeting audiences abroad) used. He was saying that Putin was the best thing that had happened to Russia. But the only thing the English-language Google knows about [Bennett] is that he spent three years is prison in the United States for pretending to be in the military," Kovalyov said.

Kovalyov began by posting on Facebook, but it proved inconvenient for including screenshots and links, so he started a blog on Medium.com — a popular platform among media professionals.

"My post [on Medium] about RT's real traffic got 60,000 hits," he said, in reference to a post about RT overstating its popularity in Western countries. The post is cited by many opposition-leaning outlets, including the blog of opposition leader Navalny.

The post challenged RT's claims of drawing millions of British and U.S. viewers. The RT reports on its own viewership had cited research carried out by a U.S. Agency, but the agency's website contained no record in support of RT's claims, Kovalyov claimed.

With every post receiving 20,000-30,000 hits, Kovalyov started a more ambitious project called NoodleRemover. "I want people to learn to see these things, to make them immune and skeptical enough" to not trust state television channels blindly as they do now, Kovalyov said.

Kovalyov currently works as a reporter and a translator, but has plans to develop NoodleRemover in his free time.

In the future NoodleRemover might become a crowd-sourcing project, where people can share fake or clearly manipulative reports, as well as taking courses on media literacy. "There is no such thing in Russia, but they teach that in Western countries, and also on the [online platform] Coursera," Kovalyov said.

When asked about the channel's attitude to someone exposing their content on a daily basis, RT spokespeople told The Moscow Times they were "happy Alexei Kovalyov has found a new occupation — having a blog about bad people that dismissed him. We will be even happier to find out that he's being paid for it," the comment read.

Delving Deep Within the Web

Ilya Klishin, 28

Editor-in-chief of the Dozhd television channel's website. Found himself interested in pro-Kremlin trolls in 2011, when a series of mass street protests, organized on social networks, sparked in Moscow. Has his own sources who share their experiences and important documents with him.

It was in late 2011, recalls Ilya Klishin, editor-in-chief of Dozhd television's website and an expert on social networks, when, after a series of mass protests in Moscow, pro-Kremlin trolls flooded the Internet.

Klishin, 28, launched the famous Facebook page for the first protest in 2011. Tens of thousand of people signed up to gather on Bolotnaya Ploshchad to protest the results of the State Duma elections.

"They were real people. But when we opened a page for the second rally on [Prospect] Sakharova, we found out the Kremlin deployed bots to this page — they had Indian and Pakistani names and wrote [their pro-Kremlin comments] in perfect Russian," he said.

Consequently, Klishin became interested in pro-government social media activities, and began exploring and writing about it for various media outlets: Vedomosti business daily, Slon news website and others.

People began reaching out to him, sharing stories and documents as proof that the Internet has an entire system of pro-government commentators.

Klishin went through 7,000 tweets in 2012, analyzing how an artificially promoted hashtag — #tukhlymarsh (rotten march), that referred to an opposition rally in Moscow — gained momentum on Twitter by real people trolling the Internet, not automated bots.

According to Klishin, the Russian government contracts so-called advertising and PR agencies, through which people are employed as pro-Kremlin Internet activists.

"It's not like there are government officials posting comments on Facebook and building up hashtags on Twitter. There are companies with people on payroll that work in shifts and spend days in their offices writing right comments in the Internet," he said.

When the Kremlin was expanding its Internet activities abroad in 2014, Klishin was one of the first to take note.

"It was then when prominent Western outlets, including The Guardian and The Huffington Post, raised the alarm about Russian trolls coming. But the panic was premature. Only now, with the topic of Ukraine slowly dying down, the main soft power of the Kremlin can launch in full gear," Klishin wrote.

Right now the system works quite effectively — it has been established and functions smoothly without major changes, the journalist told The Moscow Times.

Klishin said he would continue tracking and exposing the government's media minions, but numerous investigations by the Russian media into governmental spending on Internet trolls has failed to spark any major scandal or public outrage. "I think society is not ready, it's too apathetic right now," he told The Moscow Times.

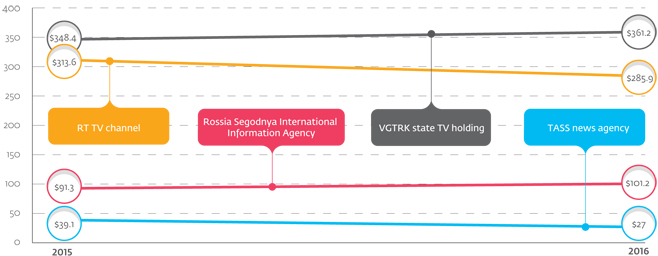

Government Funding for State-Owned Russian Media Outlets

Little Hope for Success

Klishin's sentiment was echoed by Vasily Gatov, Russian media analyst and visiting fellow at the USC Annenberg Center on Communication Leadership and Policy in California.

"Exposing lies is an important, but not a groundbreaking element of any counter propaganda work. New goals and values that would replace the ones that are [being imposed and] currently dominate in society, are," he told The Moscow Times.

Currently there are no such values in Russian society, Gatov said, that's why exposing propaganda is not effective and mostly influences a small audience — or sometimes benefits the very propaganda it seeks to discredit.

One of the purposes of propaganda is to depreciate the very concept of truth.

Russian television nowadays performs an important job — it legitimizes lies, says political analyst Vladimir Gelman. "When the television lies and doesn't even try to hide it, it sends a signal to people that there is no truth — there are simply different kinds of lies, and the one shown on television is the right one," he told The Moscow Times.

Yet Kovalyov of the NoodleRemover project remains optimistic.

That a blog maintained by a single citizen provoked such a positive response bodes well for the future. "I was surprised at first, but apparently I'm not the only one who needs all this," the journalist told The Moscow Times.

Contact the author at d.litvinova@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.