The West's new religion, that myth about the ozone layer and a conspiracy designed to undermine Russia's economic interests — these were just some of the views on climate change spouted on Russian media ahead of the UN Conference on Climate Change in Paris.

For the Russian delegation in Paris the stakes are high — the federal meteorological service said earlier this year that Russia was warming up 2.5 times faster than the global average.

But rampant climate change skepticism fueled by economic and political interests means that whatever is agreed upon in Paris, true reform is unlikely, activists told The Moscow Times.

"Russia's main [climate] strategy is to maintain the status quo," Greenpeace activist Vladimir Chuprov said.

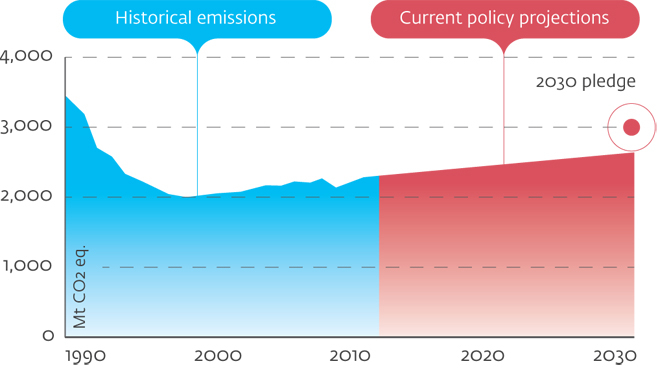

Earlier this year, Russia proposed limiting greenhouse gas emissions to between 25 and 30 percent below levels recorded in 1990 by 2030.

But environmental activists and NGOs have lambasted the Russian proposal as a smokescreen, arguing Russia is hiding behind a dramatic fall in emissions following the collapse of the Soviet Union, when much of its carbon-heavy industry went obsolete.

Over the past decade, emissions in Russia have steadily increased, data from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change shows.

Its official 2030 target would actually allow emissions to grow, the Climate Action Tracker website said, rating Russia's policy as "inadequate."

Less Fur

Russian President Vladimir Putin's traditional attitude to climate change has been a mix of mockery and skepticism.

At a 2003 climate summit, he considered the benefits of a warmer Earth, saying Russians would "spend less on fur coats," and adding, "specialists say our grain production will increase, and thank God for that."

He recently changed course and called climate change a serious problem — a development that Chuprov described as one of the biggest achievements of the past decade. But it is being undercut on a daily basis by state-run media, he said.

"The media is continuing its attack, [saying] that these are natural cycles, that it's a conspiracy by the West, that they want to bring [Russia] to its knees," he said.

It's the Economy

Some activists say domestic discussion of climate change has been muted because of its economic and political implications.

"It instantly brings up the question: Why is the climate changing? Because of the burning of fossil fuels: oil, gas, coal," prominent environmental activist Yevgenia Chirikova said.

With Russia's economy heavily dependent on the extraction of oil and gas, calls to limit the use of fossil fuels are often seen as a direct threat to national security.

"Officials from the local level all the way up have personal interests at stake in the continued development of natural resources," Elizabeth Plantan, a doctoral scholar at Cornell University researching environmental activism in Russia, told The Moscow Times.

Russia's floundering economy has played into some environmentalists' hands. Earlier this year, the state-owned oil company Rosneft froze plans to start tapping reserves of oil and gas beneath the Arctic shelf.

"Good news. For now," Chuprov said.

But there are disadvantages: With economic concerns dominating ordinary Russians' lives — real wages fell roughly 10 percent over the past year — environmental concerns lack urgency.

The government also heavily subsidizes fossil fuel generated energy, making green energy comparatively less competitive.

Ahead of the 2018 presidential elections, raising energy prices will be a hard sell for Putin, Chuprov said.

More Local

Excepting a handful of climate activists, there is little enthusiasm for the subject at home.

A petition published on the public platform Change.org calling for Russia to switch to renewable energy had gathered only 295 signatures by the start of the Paris summit.

But activists' outlook was far from gloomy.

Disasters like the smog cloud that engulfed Moscow in the summer of 2010 and this summer's forest fires on the shores of Lake Baikal have raised awareness and support for local initiatives to preserve the environment.

Growing grassroots activism could directly influence Russians' awareness of global environmental problems in coming decades, they said.

A recent poll by the BBC showed concern for global warming among Russians had risen 13 percent in the past six years.

"That's a victory," Chuprov said.

Contact the author at e.hartog@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.