Liza Alert volunteer Svetlana Popova, 33, has thought about quitting on multiple occasions. Every time a missing person doesn't get found, she said, it feels like you lose someone you know.

Yet on a cold Sunday afternoon in October, she dropped off her two children with her parents and headed to central Moscow's Belorusskaya station to help Natalya Baklykova put up posters for her husband Dmitry, who never came home after having drinks on a regular Saturday night.

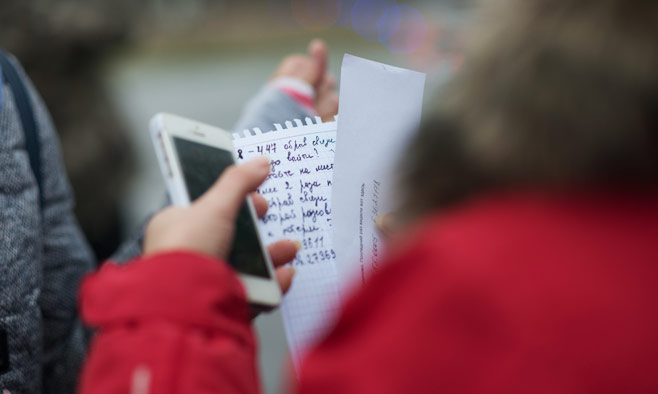

At the station, Popova runs Baklykova, 31, through a list of institutions — hospitals, homeless shelters, morgues — to call the next day. The latest evidence suggests Baklykova's husband, Dmitry Baklykov, 35, was mugged and beaten on the head, suffering memory loss as a result, and was now wandering the streets of Moscow begging for food as a homeless person.

It has become a daily routine for Baklykova and the volunteers. The posters, with Dmitry's personal details and a mugshot of a clean-shaven man dressed in a suit and tie — which the volunteers put up the day before — have already disappeared. Odds are that the posters that are put up today will also be swiftly taken down by the city's strict street cleaners.

"They consider it advertising," Popova said, shrugging. The inconvenience is just one of many obstacles hampering Liza Alert's efforts to give a face to the names of thousands of missing Russians.

A Turning Point

The organization owes its name to Liza Fomkina — a 5-year-old girl who got lost with her aunt while walking their dog in a forest in Orekhovo-Zuyevo, a town about 85 kilometers east of Moscow, in September 2010. When she was found after 10 days, the girl had died of hypothermia, her aunt already dead.

Medical examinations later showed Fomkina could still be alive if she'd been found as little as one day earlier.

The case was widely covered in the Russian media and laid bare the police's and emergency services' delayed and uncoordinated response to reports of missing children, even within a stone's throw of the city's capital.

"This was Moscow, not somewhere in Siberia," Yekaterina Demidova, 38, a self-employed entrepreneur and spokeswoman for Liza Alert, told The Moscow Times. "But there was no equipment, no experience, [the people looking for her] just walked on the streets and yelled."

Less than three weeks after Fomkina was found dead, some of the around 500 volunteers who had helped in her search founded Liza Alert to prevent the recurrence of a similarly tragic child death. But the organization soon found itself swamped with calls from relatives and friends looking for a grandparent, a relative with a disability, or sometimes just someone who, like Baklykov, had been in the prime of his life before suddenly disappearing without a trace.

Children now constitute only a minority of the cases reported to Liza Alert's round-the-clock hotline, which by September this year had logged more than 11,000 calls — double the number received the previous year — from 78 Russian regions.

The number of volunteers involved is impossible to calculate, Liza Alert representatives said. But search parties for children typically involve around 200 people, working day and night for days, weeks and months on end, Demidova said.

As of its five-year anniversary this October, Liza Alert had local units in 47 Russian regions with plans for further expansion.

As a rule, Liza Alert does not accept missing persons reports unless they have been filed with the police first.

Putting Faith in Volunteers

As a rule, Liza Alert does not accept missing persons reports unless the case has been filed with the police first, in order to set the administrative ball rolling and filter out those who have ulterior motives in wanting to track someone down, such as in domestic disputes.

But many Russians would rather put their fates in the hands of volunteers than rely on the authorities.

When Baklykova reported her husband's disappearance to the police, they replied: "Don't worry, he'll have a 'walk' around and come home in due time," implying he must be with another woman.

To Baklykova, who has been happily married for almost 12 years and has two children, aged 2 and 5, that seemed unlikely.

Her case typifies Russian government structures' laconic response to reports of missing persons, as described by Liza Alert volunteers and those whom they have helped.

"We saw from the inside to what extent no one needed [these missing people]. To what extent this babushka who got lost while looking for mushrooms in the forest was important only to her [husband] who didn't know what to do. And that no one was occupied with it," one of the founders of Liza Alert, Grigory Sergeyev, told the Ekho Moskvy radio station late last month.

A Vast Territory

Russia's vast territory and harsh climate in winter make it a nightmare for search parties. Out of the roughly 3 percent of people who are never found by Liza Alert, many are believed to have drowned in lakes, or been covered in snow and ice during Russia's harsh winters.

The other seasons present dangers too. Every year, Liza Alert sees a peak in missing persons reports during the summer and "mushroom season," from June to September, when Russians traditionally go out into the woods to pick mushrooms and berries.

In comparison to European forests, which, Demidova said, were "like fairytales," Russia's forests are often wild, densely vegetated and require specialist knowledge to penetrate.

But the existing authorities, including the emergency services, lack the professionalism and know-how to cope with such conditions, she said.

Even when they have the right equipment, rescue workers are often uninformed. She described one case in the Moscow region where rescue workers used a special vehicle equipped with a loud siren.

All of Liza Alert's equipment is paid for by the volunteers themselves or from donations.

Instead of parking in one place to give the person lost in the woods a fixed orientation point, rescuers drove it around, causing confusion.

Liza Alert frequently organizes joint training sessions with Emergency Situations Ministry workers and police. They also launch public awareness campaigns — this summer they had a stall at central Moscow's VDNKh park to teach parents and children safety rules. And they make frequent media appearances in which they explain what to do if calamity strikes, while encouraging ordinary Russians to approach disoriented people on the street who might require help.

Structural Impediments

But education and training will only take them so far — there are also structural impediments that stand in the way.

Police are bound by law to register a missing person's report straight away, but they often don't act for at least 24 hours even though in missing persons' cases time is of the essence. The chance of finding someone, whether alive or dead, drops sharply after three days, Demidova said. In the case of children or other people who can't fend for themselves, like the disabled, this can be a matter of hours, especially in winter.

Emergency workers also suspend their searches in forest areas after sunset, while Liza Alert volunteers plow ahead, she said.

There is also no unified database that allows government structures to share information across Russian cities, regions or government bodies, so officials often find themselves working at cross-purposes.

The lack of an organized approach means much depends on the individuals involved. Some officials and local politicians work together closely with Liza Alert volunteers. At other times, a missing person's case ends up in the hands of that "[police] employee who today is there from 12 p.m. to 2 p.m. and tomorrow, from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m.," Liza Alert spokeswoman Irina Vorobyova said in an interview on the "Sofa" program on the Kontr TV network.

When Sergei, 57, last month showed up at a residential building in Moscow, a place where he had lived years ago, looking disoriented, guards notified the police. Unable to answer their questions because he suffers from severe memory loss, the police then checked his documents and left him behind, standing outside in light clothing and visibly disoriented, his wife Svetlana, 48, who asked for their surnames to be withheld, told The Moscow Times.

In fact, if they had checked the Moscow region's wanted list, they would have seen that Svetlana had reported him missing in their hometown of Lobnya in the Moscow region, some 25 kilometers away, almost a week earlier.

At the moment Sergei's location was reported to Liza Alert by a bystander, Svetlana was being questioned by police as to "where she was hiding him," she laughed bitterly.

Svetlana is convinced that without Liza Alert her husband would have died from hypothermia or starvation.

The Interior Ministry, which oversees the work of the police, did not respond to a request for comment from The Moscow Times.

Liza Alert organizes frequent joint training sessions with Emergency Situations Ministry workers and the police.

No Support, Please

Liza Alert's equipment is paid for by the volunteers themselves or from small donations from ordinary citizens. Private Russian companies also contribute — mobile operator Beeline, for example, has provided the organization's free hotline and airline UTair pays for their flights.

The organization insists on remaining free of government support and other external funding and refuses to even register as a nongovernmental organization out of fear it will invite government interference, especially since Liza Alert's work frequently rubs civil servants the wrong way.

One volunteer, who asked not to be named, detailed an example of a local politician ordering posters for a missing child to be stripped down, saying it made local mothers feel "uncomfortable."

"We push the governmental machine for them to act, for them to start searching, for them to fulfill this responsibility towards society. Obviously, they don't always like that," Sergeyev said.

For a brief moment, it looked like even Liza Alert's status as a volunteer organization would not be enough to safeguard it, after Russia's Federation Council in 2013 proposed a bill to set up a government agency that would oversee the work of volunteers.

Amid widespread protest, the bill was stalled. "Thank God volunteers in our country still have the right to not depend on anyone, and we want to keep that right," Demidova said.

Critics argue Liza Alert's success plays into the government's hands. The police have been known to refer people directly to Liza Alert because it will save them work in a vicious cycle that keeps the existing weaknesses in place.

"It's concerning but we don't just want to point at the emergency services and say 'That's your job.' Our priorities lie with the people," Demidova said.

Reason to Hope

Three weeks after his disappearance, Baklykov was still lost. But his wife and friends were in a celebratory mood.

"We finally succeeded in getting a criminal investigation to be opened on murder charges!" a statement on a VKontakte page set up to coordinate his search said Friday. "Don't let that scare you, this was a necessary step for investigators to finally start doing their job. Sadly, this is the way our valiant protectors work."

Contact the author at e.hartog@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.