It was clear to everyone from the start that the authorities would not take the "Krasnogorsk shooter," Amiran Georgadze, alive. In the end, he was found dead from gunshots wounds in an apparent suicide. He was like the main character in a typical mafia movie, someone whom nobody wanted to see live — not the chance survivors of his violence, not investigators whom he might have been chummy with only days before, and certainly not anyone from the Moscow regional administration.

It is easy to dream up various scenarios. Perhaps Georgadze hid documents in a safe deposit box that, in the event of his death, would incriminate his many accomplices among the political elite. After all, at the time of his death he had his international passport with him for some reason. Did he have an escape plan? Georgadze was apparently an impulsive person and did not hide any "dirt" on his friends beforehand.

However, rumors have it that incriminating documents mysteriously disappeared from Georgadze's numerous companies during the four days that a police manhunt combed the Krasnogorsk region and found his body purely by chance in a Timoshkino village dacha next door to the dacha of the head of the Krasnogorsk region — who seems to have luckily escaped becoming Georgadze's next victim.

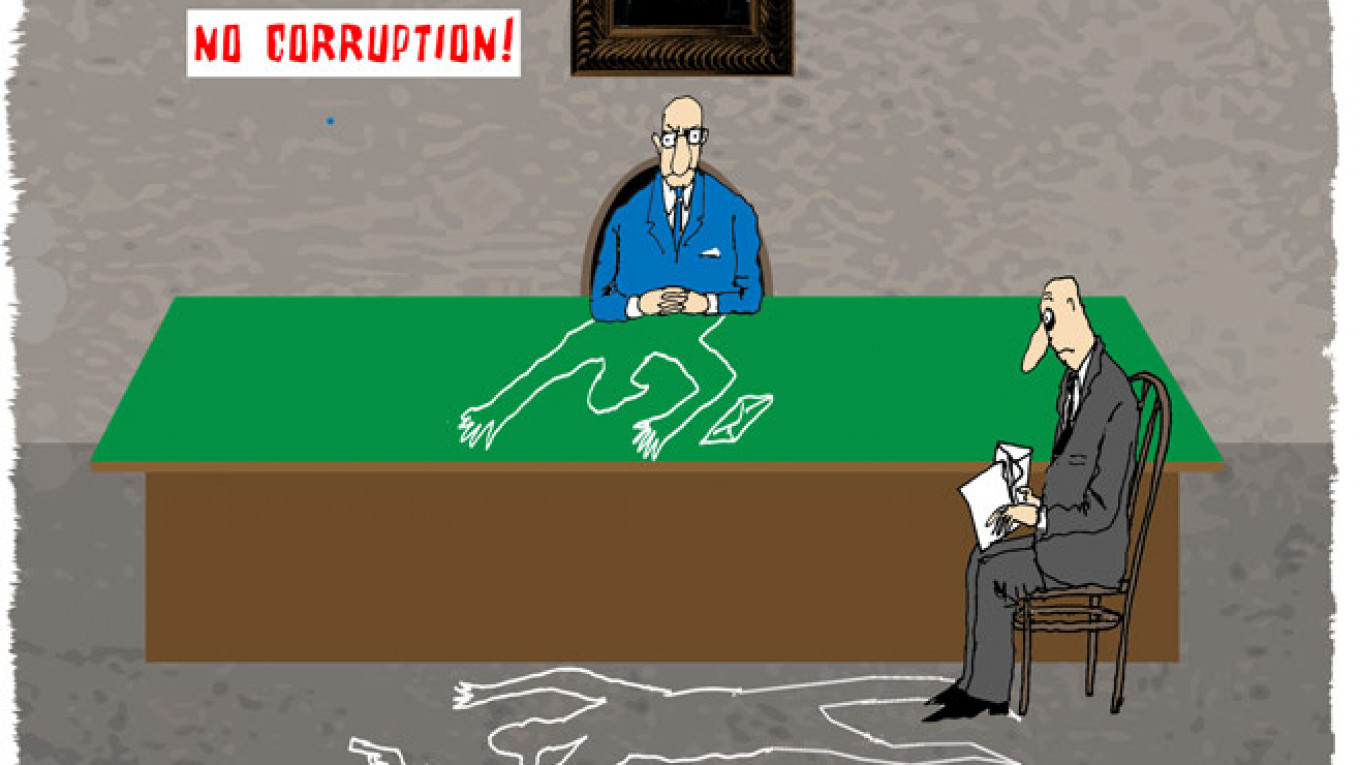

As for the investigation into the possible suicide, one famous Russian lawyer posted the following comment on Facebook: "Court-appointed forensic specialists typically first ask: 'Which conclusion did you say I should reach in this case?'"

Will the "Krasnogorsk shooter" case come under scrutiny by at least the regional authorities? Will they look into conflict of interest claims against the officials who grant building permits and land grants and pay closer heed to complaints coming from citizens? Regarding the latter, Moscow region activists have posted a great deal of evidence on social networks detailing misconduct in construction and land allotment. This includes lucrative rights to forests that very suddenly and conveniently became infested with bark beetles.

Citizens' complaints reached the district and regional heads, and probably the offices of the Federal Security Service that stand only one floor above the crime scene. Thankfully, none of those workers were hurt in the attack.

Now officials are checking into claims on social networks that an entire high-rise apartment building was erected and sold to new residents without having been hooked up to the central water line and sewage system. And whereas regional officials previously had no time to check into such rumors, now they are determined to get to the bottom of things.

Of course, senior officials had no idea what schemes their subordinates had hatched, and in order to find out, they had to take over authority for land allotments from the head of the Krasnogorsk region. And apparently as a result, local officials could not honor their illegal promises to Georgadze, or return his $20 million and the "advance" they had earlier received. It was a force majeure situation.

It is easy to imagine that investigators will now closely examine those areas where business intersects with officials who are on the take — land allotment, building permits and connections to the power mains; how tax officials will diligently check every single businessperson to confirm that their real expenses do not exceed their declared incomes; how officials will go back and question activists to obtain useful information and resurrect and look into all the Moscow region scandals that had been successfully hushed up in recent years; and how they will go after every person who signed off on a building that was never connected to the city's sewage system.

However, none of that will happen. At most, one person will get dismissed: Krasnogorsk regional head Boris Rasskazov, who has served as his post for decades and who narrowly escaped death at the hands of the "unlucky" businessman.

Admittedly, this system has learned how to limit the negative fallout from such "unusual situations" in which one such excess can uncover a gaping hole of corruption so huge that anyone gazing into its depths would spontaneously exclaim, "This whole system is rotten to the core!" The Moscow region is not unusual in this regard, but the authorities are skilled at explaining away such incidents as the result of a personal feud between the killer and two of his victims — and nothing more.

The system works in this way for its self-preservation. Any attempt to thoroughly "clean house" could lead to such brutal internal feuding that the system would simply collapse — especially if any outside "bloggers" are allowed to have their say about such revelations of misconduct. After all, anyone outside the system is, by definition, unmanageable and therefore "politically irresponsible."

Better not to let that anti-corruption genie out of the bottle because there's no telling where it will end. That risks implanting a dangerous idea into the brainwashed minds of the population — namely, that the authorities not only steal, as people already know, but that they could be dismissed for such minor misdoings.

Putin alone has the right to decide who stays and who goes, and not because this one stole or didn't steal, but because "that's how it's done" in the backroom battle between economic entities for an ever-shrinking cut of the financial and material resources available. And if people get this idea into their heads, they begin thinking of themselves as the arbiters of the political process. And rulers consider that more dangerous than even the most monstrous corruption.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.