A recent three-day visit to Germany gave me the opportunity to see the daily news from a new perspective. There, Russia's military adventure in Syria was summed up in two sentences scrolling across the bottom of the screen during the news broadcast. They read: "Russian air force supports attack by Assad's army," and "Russians allegedly used cluster bombs." I can't say I spent all three days glued to the TV screen, but those two phrases seemed to capture the whole of the subject as portrayed in German news.

I did not discuss the war with any of the Germans I met on this visit, but those brief news items conveyed the thinking there very well: "Everything is clear with the Russians. Not surprisingly, they are again waging what is probably unconventional warfare somewhere."

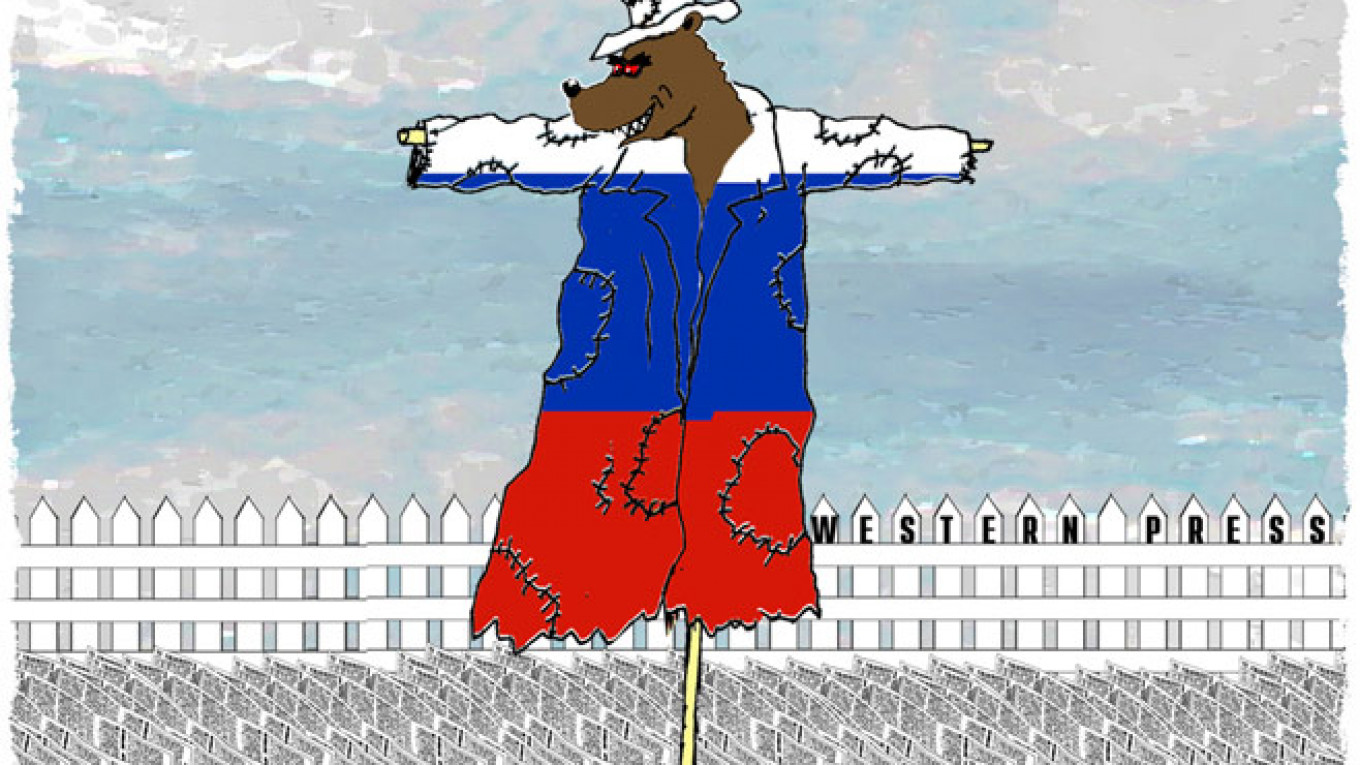

Ever since the annexation of Crimea last spring, it has been difficult for me to shake the feeling that for Westerners Russia is again an aggressor, a revisionist power. And ironically, it is simpler for many in the West to perceive Russia that way than as a country trying to overcome its totalitarian past, build a democratic system and a market economy. The image of the aggressor is more familiar and comfortable.

Many people in the West were always skeptical about Russia's motives during the 25 years of detente, perestroika and the more recent "reset" in relations. They believed that, behind all that pacifist tinsel was the real Russia that prefers arguing its political theses through force. And then, they argue, Russia dispensed with its camouflage and showed the world its true colors. "You see? You see?" they said. "You called us conservatives and Cold War hawks who were forever stuck in the past. But we were right!"

As I left Germany, I had the opportunity to exchange a few remarks with the German border guard who checked my passport.

"Do you live in Germany?" he asked after we greeted each other in German. "No," I answered, "in Moscow." "How do you know German so well," he asked, although he was only referring to my ability to maintain an elementary conversation. "I studied in school," I said. "In school? Wow! They teach German in Moscow schools?" he asked. "That was during the Soviet era," I answered. "You studied it voluntarily?" he inquired. "Yes, of course," I said. "That's amazing" he responded. "Thousands of Russian Germans moved here, but many of them don't know a word of German. (This was a reference to the 18th century German settlers to Russia whose descendents migrated in large numbers back to Germany in the 1990s and 2000s.) "However, your President Putin speaks German," he added.

I felt disconsolate at our conversation. My fond childhood memories of school exchanges with West German students, the happiness we felt in discovering that we were all ordinary humans — without tails or horns or hooves — and the decades-long friendships that ensued, all seemed to have become part of some passing dream. Now, 25 years later, I was standing with a German border guard who was surprised that they teach German in Moscow schools.

In short, Russia has assumed its usual place on the periphery of Western perceptions of the world, and it is no exaggeration to say that this is the place of a monster, a horror story dating back to the Russophobic thinking that prevailed during the Crimean War. And of course, this same thinking informed the international investigation into last year's downing of Flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine.

It is anyone's guess as to how decisions are made in today's Kremlin. However, it is safe to say that Moscow leaders do not like the role of monster in which they have been cast since the start of the conflict in Ukraine, at the very least because it complicates all of their economic activities.

But more than that, it indicates that something is very wrong in Russia's relations with the West. And if the West believes that the Kremlin is inhabited by rational, thinking people, is it too much to imagine that those people have realized that the situation Ukraine is ruining Russia's reputation, and that the best way to restore it is for this country to prove itself somewhere else, somewhere that the world is fighting unmitigated evil?

If there had been no Syria, Moscow would have had to invent it. The fact is, it has everything Moscow needs: absolute evil in the form of the Islamic State, Syrian President Bashar Assad, whom at least he and Moscow consider the country's legitimate leader, and an ambiguous situation in which the West empowers and instructs groups fighting against Assad, thereby playing into the hands of the Islamic State.

Moscow has not directly accused the West of failing to hit hard enough against Islamic State terrorists, but it has dropped numerous hints to that effect. Russia probably does not want to do more than simply hint, because intensifying the argument over who is bombing who might quickly lead to a direct confrontation between the Russian and Western militaries. The moment that were to happen, it would force Russia into the very role of monster that it was trying to shake off, and so the best option is to maintain the ambiguous nature of the situation.

That also has the advantage of enabling the Kremlin to continue its anti-Western propaganda. After all, for 18 months Moscow has presented the war in Ukraine as a conflict between Russia and the West, and the Kremlin would have trouble explaining why its former archenemy is suddenly an ally.

Almost every step the West makes in the current situation only helps the Russian leadership. "You say we bombed the wrong positions," President Vladimir Putin openly asks. "Then show us where you believe the real terrorists are located. You won't show us? You say there is no agreement yet for the exchange of intelligence between Russia and the U.S.-led coalition? We won't say it to your face, but doesn't that indirectly help the Islamic State?"

Those Russian arguments no longer look so weak. Their only problem is that they work well only on the domestic audience. Today's Russians are the grandchildren of those who Kremlin propagandists had once convinced that, although the United States, Britain and France were allies of the Soviet Union in the war against Hitler, they were capitalists like the Germans and therefore delayed as long as possible in opening a second front in Europe.

Those propagandists failed to mention that former Soviet leader Josef Stalin was in league with Hitler from 1939 to 1941 or that the U.S. and British Lend-Lease Act supplied the Soviet Union with billions of dollars in aircraft, tanks, trucks, jeeps, food and other vital supplies during the war years.

The current claim that the U.S. does not really want to fight the terrorists is reminiscent of those stories about the second front in the sense that it is also possible to explain, but the world is actually more nuanced than that. However, the domestic audience cares little about such nuances.

And the foreign audience, for the sake of whom this whole venture was apparently undertaken, couldn't care less. It is not the domestic audience that will determine whether Russia remains a bogeyman. The problem is that the West cares little for such mental exercises as Soviet claims about a delayed second front. Russian aircraft in Syria are only a rolling caption — without pictures — on the evening news in the West.

It seems the West has already made its decision, casting Russia as the bogeyman and not as the leader of an international anti-terrorist coalition.

There is nothing new or frightening for Russia to find itself in this situation: it has played the role of bogeyman more than once in the past, and even managed to leverage some technical and political modernization from military defeats, as happened during the Crimean War of 1853-56 — not to mention from military victories.

But as for victory, it is necessary to first understand how it will look and what price Russia will have to pay for it. If this is a serious war, then those considerations are paramount, and not how it looks on television — whether it appears as a triumph for Russia's struggling military-industrial complex or as two lines of rolling text on German television screens. Those who had their hearts set on the former are definitely in for some unpleasant surprises.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.