Seventy-five percent of Russians approve of committing people who suffer from mental illnesses to psychiatric institutions against their will, a survey by the independent pollster Levada Center revealed earlier this month.

"In Russian society the level of social trust is low, as is the feeling of safety, and that's why Russians try to keep away from those they consider dangerous," Karina Pipiya, a sociologist for the Levada Center, told The Moscow Times in written comments.

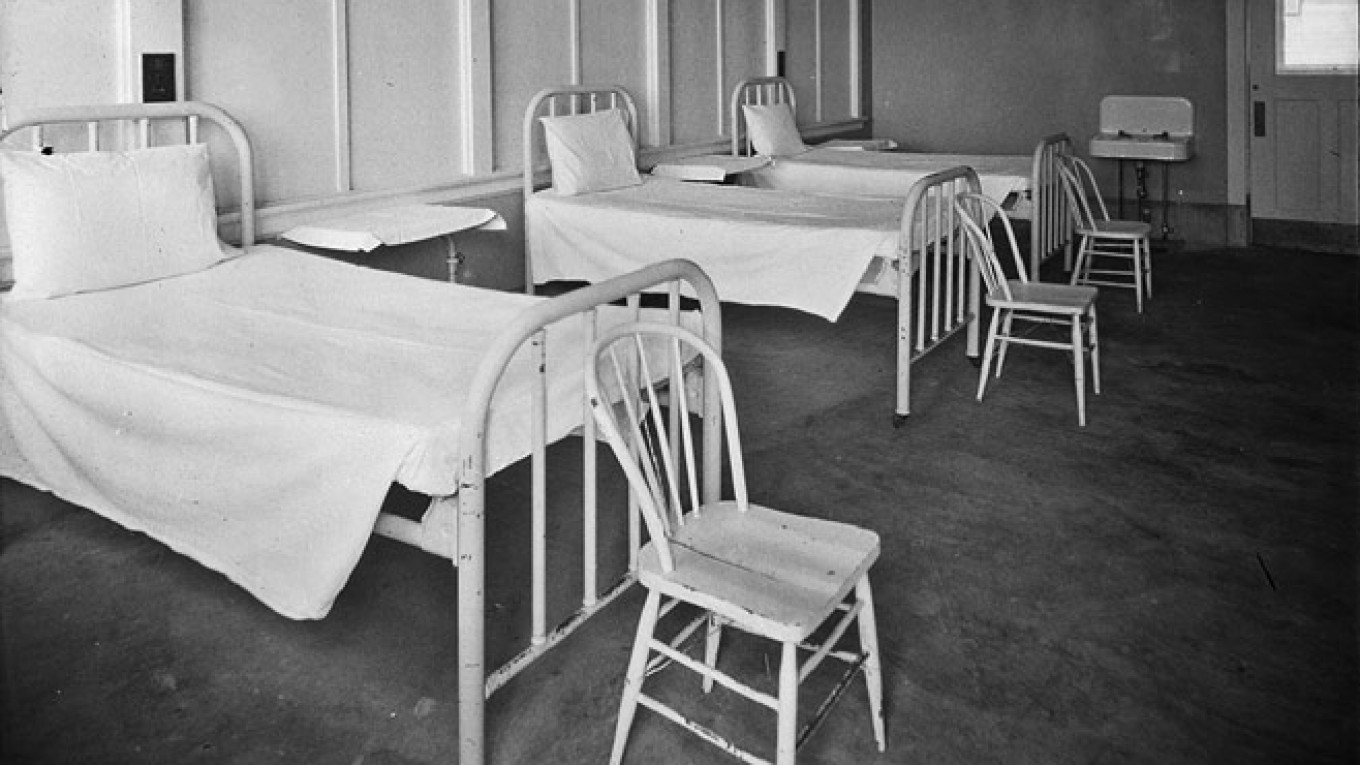

Dangerous or otherwise, thousands of people in Russia spend decades locked up in psychiatric care homes: facilities for people with psychiatric or neurological disabilities who are deemed incapable of living on their own and who have nowhere else to go or no one to take care of them.

In April this year, there were 531 psychiatric care homes in Russia with more than 150,000 residents, officials said at a social workers' forum in the city of Yaroslavl.

As of Jan. 1, out of 1,917 buildings occupied by psychiatric facilities, 63 were in need of major renovation work, 47 were declared dilapidated and 17 were in a critical state, Nadezhda Uskova, deputy minister for social security in the Moscow region, was cited by the Argumenty i Fakty newspaper as saying.

Russia's psychiatric homes have been described by media and human rights advocates as prisons where residents are stripped of their rights and pumped full of strong psychotropic medications while the administration takes advantage of their helplessness to appropriate their property and welfare benefits.

But some experts argue that the picture is not so dire, and that patients can benefit from staying in such facilities with the help of competent specialists and charities.

The one thing everyone agrees on is that the system is outdated and needs reforming.

"The standards [under which the homes operate] are outdated, they basically copy the standards in place 50 years ago," said Vadim Murashov, a psychiatrist and former director of a care home in Moscow. "But life changes, and reforms in this sphere are inevitable," he told The Moscow Times in a phone interview.

Unhappy Home

Alexander Prokhorov was sent to a care home in St. Petersburg directly from an orphanage after he turned 18. He suffers from severe kyphosis (excessive curvature of the spine), and says he was also diagnosed with learning difficulties in order to make him eligible for incarceration in a care home.

Prokhorov, 31, spent more than 10 years there before he finally got the apartment to which he was entitled by law as an orphan.

He describes his years in the facility as far from happy. The building was old and dilapidated, the food was bad and residents were forced to take psychotropic medications and threatened with being committed to a mental hospital for bad behavior, he told The Moscow Times in a phone interview.

"Do you think I would've left [to live in my apartment] if it was a good place? If I had been able to get back massages [for his condition], or [exercise] in a swimming pool? But there was nothing," Prokhorov said.

There was physiotherapy, he said, but "most of the time the instructor just sat there and played with his phone, telling me to do it on my own."

Andrei Druzhinin, 33, was diagnosed with autism as a child and was committed to a care home when he was 28 by his aunt, who took possession of his apartment in the center of Moscow.

His girlfriend Nadezhda Pelepets describes him as a man fully capable of living a normal life — just shy and sometimes impractical. His aunt, an employee of a psychiatric institution herself, had him committed to a mental hospital where he was diagnosed with a psychiatric condition. Soon after the court declared him incapable and sent him to a care home.

The four years Druzhinin spent in the facility seriously damaged his physical and emotional wellbeing, Pelepets told The Moscow Times, because he was forced to take strong medications that he didn't need, and because life there was monotonous and depressing.

"There was a corridor, and a room with a TV set," she said in a phone interview. "So he could walk along the corridor or watch TV, and basically, that's it," she said.

The facility's administration resisted her attempts to take him out — even for a few hours or a day — to make his life more interesting, as well as her attempts to have him declared capable, she said.

"The only reason Andrei got out was because I officially became his guardian," she said.

Rotten System

There are three types of residents in psychiatric care homes, said Tatyana Malchikova, president of the Civic Commission for Human Rights, an NGO that specializes in human rights violations in psychiatry.

There are those who suffer from serious neurological or mental illnesses and need specialized care, orphans who have had to leave their institutes after turning 18 and have been diagnosed with psychiatric conditions, and those who were falsely committed on the basis of a fabricated diagnosis.

"The system of psychiatric care homes is the most rotten part of the country's psychiatry infrastructure," Malchikova told The Moscow Times in a phone interview.

"Most of the complaints we've dealt with during the last 15 years concerned psychiatric care homes," she said.

All orphans declared to have psychiatric or neurological disabilities are sent to live in psychiatric care homes after they turn 18, the human rights advocate said. Most of them are diagnosed with learning difficulties, but that's often incorrect, she said.

"These children often don't know how to read or write; they behave inappropriately because no one worked with them, no one taught them," which gives social workers grounds to conclude that they have learning difficulties, Malchikova told The Moscow Times.

So instead of getting their own apartments as orphans are entitled to by law, they end up in care homes — along with adults put there by relatives who want to claim their property or other assets.

"The scheme is simple. A person reports their relative as dangerous to society to the police or nearest psychiatric institution, then commits that relative to a mental hospital where they are pumped full of drugs," Malchikova said.

"Then the person goes to court and demands that their relative be declared incapable. Even if the relative is present at the hearing, imagine the condition they're in after all the medications they have been given: They look [unwell] and behave oddly, so the judge easily declares them incapable," and the relative is sent to a psychiatric care home, leaving their property at the disposal of family members, she said.

"But the most frequent violation is declaring kids [from orphanages] incapable without them even knowing," she said.

"This way the care home becomes the guardian of its residents and is allowed to use their property, whatever that is — real estate outside of the home, or any welfare payments they receive, or other things," she told The Moscow Times.

Residents of these facilities are often kept under lock and key, according to Malchikova, with their passports confiscated by the administration and medical staff giving them strong psychotropic medications and punishing them for "bad" behavior.

Means of punishment vary, she said. The care home administration may seize their property, such as phones or laptops, send them to a psychiatric hospital or simply lock them up in improvised punishment cells, just like in prison.

From the Inside

Harrowing tales about psychiatric care homes are often exaggerated, said Murashov, who worked as the director of a care home in Moscow in 2011-12.

"No one deliberately wants to harm [the residents]. Of course, there are exceptional cases, but these days they quickly become public knowledge and a liability for the facility," he told The Moscow Times.

Murashov said residents' problems are caused by a lack of competent specialists.

"It's not that they deliberately pump the residents full of medications," he said. "It's just that the standards [of psychiatric care] are outdated, new ones need to be introduced. So they consider it normal to do things that were [normal] 50 years ago," he added.

There are no gerontology specialists working at the care homes, Murashov said, and most of the officials responsible for this sphere have a very vague idea of how a psychiatric care home should function.

At the moment, care homes have too many medical staff, the psychiatrist said, when the facilities should focus on nursing instead of treating. "Nursing [the residents], taking care of them, providing psychological support — that's how it works in other countries," he said.

The psychiatrist believes care could be improved if the government joined forces with the private sector. "These facilities should be organized as public-private partnerships" because it would raise the quality of the services provided, he said.

Reforms on Their Way

The system of psychiatric care homes needs reforming, said Yelena Topoleva-Soldunova, a member of Russia's Civic Chamber that monitors the situation in the homes together with NGOs and human rights activists.

"The system is ponderous, it was formed a long time ago and it is difficult to change it and carry out reforms. But at the same time it is so outdated from the point of view of both medicine and social services that changes need to be made," Topoleva-Soldunova told The Moscow Times in a phone interview.

Society and NGOs realized this some time ago, she said, and have recently started a dialogue with decision-makers. "We've put together a working group at the Labor Ministry and started discussing ways of reforming the system," Topoleva-Soldunova said.

She echoed Murashov's statement about outdated standards and said that today, providing food and basic necessities was not enough for the residents of the homes.

"We want them to lead dignified lives there, or be adopted by families, or live on their own [outside the care homes] if they're capable of doing so," Topoleva-Soldunova said.

First and foremost, according to her, reform should be aimed at preventing teenagers from orphanages being sent to care homes, because they don't develop there: They don't study or work, and spend their days surrounded by walls and fences.

A lot of them can live on their own with the help of social workers, said Topoleva-Soldunova.

Another important goal is to initiate rehabilitation for residents of care homes whose condition is serious. At present they are often simply constrained to their beds. "But medical science is moving forward, and a lot can be done for them," said Topoleva-Soldunova.

Despite all these problems, a lot has been done in the last five years, she said.

"A few years ago no one was talking about protecting residents' rights or about the homes being like prisons," she said.

"A few years ago, psychiatric care homes in Russia were burning down all the time, a lot of people died in those fires. At least the buildings have been modernized since then and it's no longer dangerous to live there. We solved this problem, now it's time to solve the other problems," said Topoleva-Soldunova.

Providing Human Contact

Irina Kolesnikova, a sister of mercy from Miloserdie (Mercy), an

Orthodox charity service that supports people in need, works at one of

Moscow’s psychiatric care homes along with eight other sisters.

She refers to the residents as “kids” and explains gently that

she sees them all as children, regardless of their age. Kolesnikova said

that the one thing residents of the care home really miss is attention,

and that’s what the sisters of mercy provide them with, by taking them

for walks, reading to them and talking to them.

“We don’t do what the care home staff do,” Kolesnikova told The

Moscow Times in a phone interview. “We talk to them, read, sing. … They

miss human contact,” she said.

Human contact is the best form of rehabilitation for the residents, Kolesnikova said.

“Psychiatrists claim that kids older than 18 are almost

impossible to rehabilitate if no one has worked with them before. But

I’ve seen three kids who actually started to walk and several girls

started to talk, which they had never done before,” she said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.