Will Syria become a second Afghanistan for Russia? Is it wise for Russia to intervene in that conflict? Rumors are circulating that Moscow is planning a face-saving maneuver whereby it gradually “hands over” the Donbass in fulfillment of the Minsk agreement while aiding the U.S.-led anti-Islamic State coalition in Syria to get back on good terms with the West. The plan sounds good in theory, but it looks unfeasible in practice.

The White House remains implacable toward both the regime of Syrian President Bashar Assad and the possibility of Russia providing military and technical assistance — much less troops — to aid his forces. The U.S. called on its allies to close their airspace to Russian aircraft flying to Syria.

Judging from the tone of the messages out of Washington, the West might soon impose sanctions against Russia for its role in Syria, in addition to its role in Ukraine. Because Assad carries out massive air strikes against residential areas occupied by the “opposition,” the West views him as the main culprit behind the suffering and deaths of civilians. That prompts the logical conclusion that, by helping the Assad regime, Russia is only exacerbating the humanitarian crisis in Syria and not contributing to its resolution.

The U.S. is very close to declaring a “no-fly zone” for Syrian aircraft over part of the country. Washington already conducts airstrikes against Islamic State forces in Syria without informing Damascus.

The U.S. also supports the efforts by Turkey — which recently joined the ranks of the anti-Islamic State coalition, and whose security forces until only recently were flirting with and even supporting the Islamists — to create a “security zone” along the Turkish-Syrian border.

That is, the scenario for the de facto partitioning of Syria might already be in motion. And the West has no desire to indulge Russia’s apparent desire to help Assad maintain control over at least the Latakia region, the stronghold of the country’s ruling Shiite Alawite sect.

Washington is particularly concerned about rumors of possible coordination between the actions of the Russian and Iranian militaries. These rumors first emerged following a secret meeting that President Vladimir Putin and Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu allegedly held one month ago with Iranian Major General Ghasem Soleimani, the commander of the elite Quds Force in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard.

Although Moscow denies that there was a visit or that it held talks with Soleimani — whom the UN has sanctioned and forbidden to leave Iran — rumors of increased Russian military involvement in Syria began soon afterward.

If Putin is hoping to “sell” his participation in the Syrian settlement during his upcoming speech before the UN General Assembly in the same way that he “sold” his plan regarding Syria’s chemical weapons back in 2012 — and which U.S. President Barack Obama viewed as a positive step — he is probably in for a disappointment. The West is in no mood to “buy” anything from Moscow now that relations have become so thoroughly soured over Ukraine.

As for the idea of “handing over the Donbass” in exchange for another brilliant operation by Russia’s “polite men in green” — this time in Syria — the fans of complex military-political moves are probably exaggerating the possibilities this time. Life in Russia and the political discourse here are both simpler now.

The average Russian is tired of hearing about Ukraine. Events in so-called “Novorossia” have clearly lost their former importance and drama. If control over the Russian-Ukrainian border in the Donbass were to pass into Kiev’s hands tomorrow, Russian public opinion would not react, save for a few jingoistic bloggers.

And the threat that thousands of volunteers who fought in the Donbass would return home and destabilize the situation in Russia is, I think, also greatly exaggerated. Once upon a time, a far greater number of Afghan war veterans returned home, and did they play any substantial political role in the country save for opening certain types of businesses and conducting what might be called “security arbitration” activities? No.

The same is true of veterans of the two Chechen wars, any of whom might take offense at the current “triumph” of Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov — himself a veteran of those wars. The most that returning Donbass volunteers might achieve in Russia’s political system is to get their names on the election lists of some fringe parties that have no chance of ever winning an election.

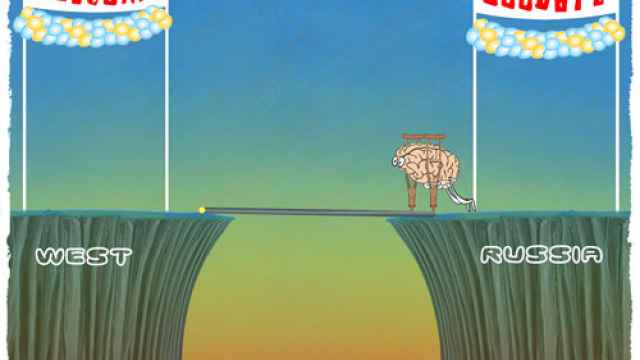

It is another matter that the Donbass and “Novorossia” remain the subject of contentious political bargaining between the Kremlin and the West. Moscow will not just give away the Donbass for a song. Russia will try to wear the West down, hoping that Europe will eventually get fed up with Kiev and its decidedly un-European political culture and practices. Moscow might eventually win special status for the Donbass, if not de jure, then at least de facto. The Kremlin will probably choose not to aggravate the situation there so as to avoid any additional sanctions and extra problems at home.

On the other hand, Russian leaders have already done a good job of proving that the sanctions have not had the “devastating effect” that the West had only recently anticipated they would. As the Kremlin predicted, Russian society is not complaining in the least. The ruling elite are highly unified, at least outwardly, and nobody is carrying Putin’s “head on a platter” to Washington.

Will Syria become another Afghanistan for Russia? Does it make sense for Russia to meddle in this situation when it has serious economic problems at home? The answer to the second question is seemingly obvious: “Foreign adventures” should be the last thing Russia needs right now.

On the other hand, there is no guarantee that Moscow or the Russian economy would benefit in any way from “handing over” Assad. Bilateral relations are so bad now that the West is unlikely to reward or thank Putin’s Russia, no matter what it does.

In fact, Syria will not become another Afghanistan for Moscow. Russia will not interfere in that conflict on a scale even remotely comparable to its role in the Afghan war. The Kremlin will probably opt for something resembling the “hybrid war” in Ukraine, only this time in place of “volunteer” fighters, Russia will provide, for example, “guardians of the Islamic Revolution.”

The result is that the field for large-scale and dangerous geopolitical games is becoming wider and the players more numerous — with each striving to achieve his particular goal. None are willing to consider the long-term consequences or to talk with opponents about a possible compromise. And that is exactly how mankind has, at various times in its history, ended up getting drawn into major wars.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

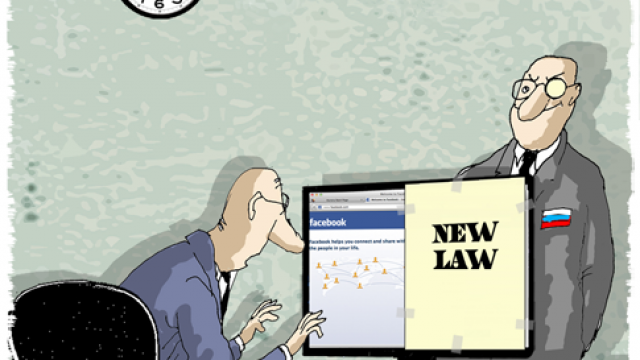

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.