The Russian Internet giant Yandex put its literary research hat on to conduct a far-reaching survey into the habits of Russians who search for poets and their works online. After analyzing the 37 million Yandex searches related to poetry over the period of one year, April 2014 to March 2015, they put together a kind of snapshot of Russians’ taste in poetry, poems and poets.

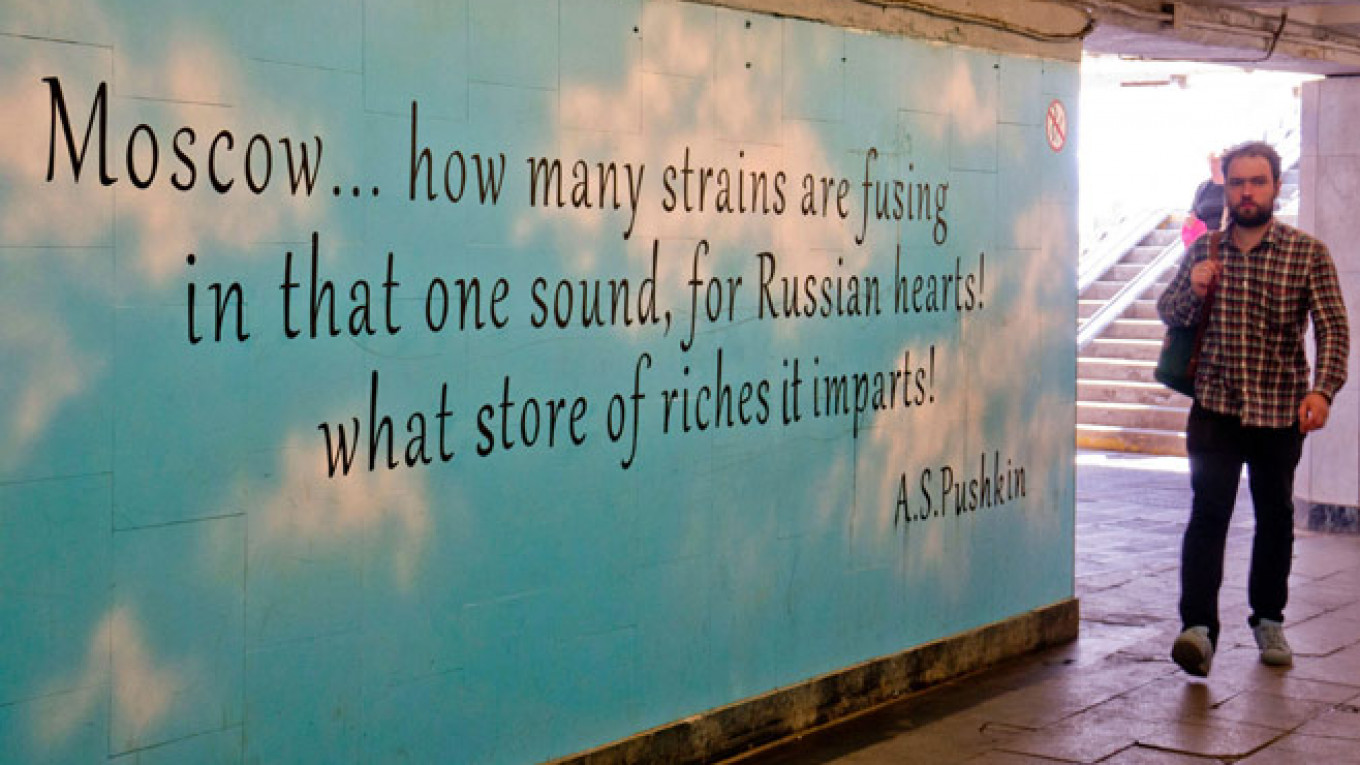

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the poet most frequently searched for was Alexander Pushkin, whose works were the objects of over 6 million searches, making up a hefty 18 percent of all searches registered over the year. Following behind him in second place was his Golden Age companion, Mikhail Lermontov, with over 2.5 million searches and 7.6 percent of the year’s searches. In fact, the 19th-century Golden Age poets as a whole took 32 percent of all registered searches with other big-hitters including Ivan Krylov in 10th place, Alexander Griboyedov in 20th, and Vasily Zhukovsky in 24th.

For ordinary Russians, this outcome is not much of a shock. Tatyana Pavlova, a Russian teacher at a Moscow language school, said in an interview to The Moscow Times, “When you think about Russian poetry, you immediately think of Pushkin and Lermontov. There’s a little game you can play: ask a Russian to free associate. You say ‘color,’ they say ‘red.’ Fruit? Apple. Poet? Pushkin. It’s always the same.”

Pavlova guessed that the writers of the Silver Age — late 19th and early 20th century — would be next in the Russian poetic psyche, and she was right. The Yandex poetry data showed that Silver Age poets registered just slightly less than the Golden Age poets — 26 percent of the searches made in the time period, with a cluster of the most famous poets of the early 20th century taking many of the top spots — Sergei Yesenin in third with 6.5 percent of all searches, Alexander Blok in fifth with 3.3 percent, Vladimir Mayakovsky in seventh with 2.9 percent, and Anna Akhmatova close behind in eighth with 2.7 percent, just under a million, of the searches registered.

Yandex did not simply compile a list of the Russian poets most frequently searched for, but extended its investigations to particular works. The most sought-out work by Pushkin was “Eugene Onegin.” That work was sought out almost 1 million times — making it the poem most searched for — but it was the object of only 15 percent of all searches related to Pushkin.

And although people looked for a variety of works by Pushkin, every single one of the 310,000 searches related to Golden Age poet Alexander Griboyedov was related to his work “Woe From Wit” (“Gore ot uma”).

The writer with the greatest number of known poems? Marina Tsvetayeva. Over the course of the year, people looked for 1,260 different poems by her. Next in popularity by number of poems was Anna Akhmatova. Even though less than 3 percent of the searches were for her poetry, people looked for 858 individual poems. In third place was Pushkin, with 777 poems or works sought out.

Russian women looked for poetry online 3.5 times more often than men.

The most sought after poem — or part of a poem — was Tatyana’s letter to Onegin in “Eugene Onegin.”

But users who searched for “Eugene Onegin” did so with 45,000 different search entries, covering a wide range of lines taken from the novel in verse. This gives proof to the assertion that Russians have a phenomenal store of memorized poetry. With learning poetry by heart taught in schools to generations of Russians, this feat of memory is nowhere more effectively illustrated than in a clip commissioned by the independent Russian TV channel Dozhd, called “The Power of the Word.” In this short video, actors get on a Moscow trolleybus and begin reciting the love poem by Pushkin that begins “I remember that moment of wonder …” (“Ya pomnyu chudnoye mgnovenye …”) as others gradually join in the spontaneous recital.

Despite this collective national breadth of knowledge, changing times could be affecting the youngest generation’s ability and desire to memorize poetry. Yekaterina Marusanova, a fellow teacher with Pavlova, believes the trend toward reading less and watching more means the manner in which people absorb quotable lines has changed. “People like to quote lines that sum up the epitome of the Russian mentality for them. That’s why someone like Vladimir Vysotsky — 14th most popular by search entries with 560,000 annual queries — is so popular.

“But nowadays romance has left our lives, so people don’t bother to learn poetry and quote them; they have films for that. There is a secret language of film quotations in which youngsters communicate, and it’s just a progression from quoting poetry.”

Even though young Russians might be losing their touch at learning poetry by heart, they are still far ahead of Westerners. Alexander Walmsley, a student at the University of Oxford, told The Moscow Times, “When I think of English poets, I think mostly of the Romantics like Byron, Keats, Shelley and Wordsworth, of course. Then there are the war poets like Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. In general, though, English people don’t know their poetry as well as Russians do — we can probably quote a line or two of Wordsworth, but not much more. I think we know the names, but less people have actually read it.”

For the full analysis in Russian, see yandex.ru/company/researches/2015/ya_poetry.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.