Russian media could not ignore the recent survey by state-run pollster VTsIOM measuring Russians' attitudes toward the United States. The headlines in almost every pro-Kremlin and even opposition publication declared that Russians consider the U.S. an immoral and unspiritual country.

However, the survey results that were sent to news commentators across the country actually showed that only 15 percent of respondents hold that view. Though that is clearly more than felt that way 20 years ago when enthusiasm over the fall of the Iron Curtain was at its highest, it is hardly a figure that justifies such categorical headlines. Only 15 percent of those questioned consider the U.S. immoral and unspiritual — not all Russians, and nowhere close to a majority.

The results from even Russia's major sociological research centers such as the pro-Kremlin VTsIOM and the more independent Levada Center no longer inspire confidence. Even their staffers admit that the quality and accuracy of their work has fallen lately. And one reason for the decline is that fewer Russians agree to respond to their surveys.

Field workers must now knock on approximately seven times as many doors as before to find a home whose residents are willing to answer their questions. Nobody — not sociologists, government officials or fellow Russians — know what those reticent citizens are thinking.

The result is that any diagnosis of Russian society involves so much guesswork that Western sociologists no longer put any faith in the "big data" coming out of this country.

Even the idea that 86 percent of the population supports President Vladimir Putin and 14 percent opposes him is little more than a theory that has gained currency in both domestic and foreign media through the force of repetition, but that lacks any grounding in empirical data.

Even the survey on attitudes toward the U.S., although it seems like an attempt to either confirm or deny a certain sociological hypothesis, is based on nothing more than a propagandistic ploy.

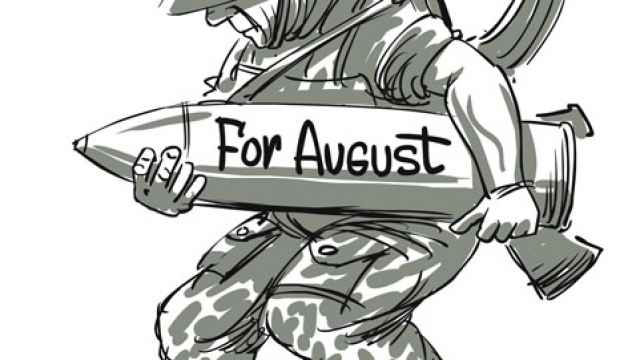

Many might believe just the opposite, that Russians are even more anti-U.S. than popularly reported and that most residents in single-industry towns hardest hit by the current crisis, and who now earn the equivalent of $120 per month at the current exchange rate, would gladly jump into the cockpit of a tank or fighter plane to combat hostile U.S. imperialism.

However, too much evidence exists to the contrary.

For example, "sources familiar with the situation" occasionally claim that Russia has 50,000 volunteers in the Donbass. However, that is ridiculously few from a country of 145 million that is inundated with anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western propaganda day and night.

Also, hundreds of thousands of people must resolve the practical task of protecting their incomes and savings as the value of the ruble declines. Most who convert their money into dollars and euros have never visited Europe or the United States. Perhaps they watch the state-controlled Channel One, vote for Putin and believe that Russia's actions in Crimea are absolutely right.

But at the right moment they shake off the cobwebs of propaganda and pragmatically opt to buy U.S. dollars so as to purchase that new furniture set before the ruble price goes through the roof.

The very fact that Russians are wondering what to do with what little savings they have shows that the economic culture has changed from what it was even 10 years ago. Sociologists have identified some of those changes in attitude, but not all, in part because they did not always know which questions to pose.

The only thing we can say with certainty about Russian society is that it differs significantly from the picture painted of it by state-controlled television.

If to look only at television reports, it is very difficult to shake the feeling of impending disaster. It even seems strange that the street is not full of columns of angry uniformed men carrying torches and marching to the attack.

There is no official data to indicate just how universal this sense of disaster is. That feeling might be confined to people interested in political science and modern political history, or the general population might feel it also. Any chance conversation with Russian people — at a moment when they are not watching televised state propaganda — reveals the true level of frustration over the current crisis and uncertainty in the future.

The tendency among many Russians to expect the end of the world stems from modern and recent Russian history. It is a tragic story with millions of war victims, exile, famine and prison camps. However, other countries have also experienced such tragedies. The difference is that Russia has not yet come to terms with its most tumultuous upheavals.

Historians relate the events of 1917, the Russian Civil War, the purges of the 1930s, the war with Nazi Germany and the Soviet collapse in 1991, but the deeper reasons for them and their psychological and social consequences have yet to find a place in the national consensus. The result is that Russians see their past as a vaguely horrific time, and because its underlying causes and effects remain so little understood, Russians have a vague dread that the same events might repeat themselves in the future.

That is why an increasing number of Russians are trying to escape impending disaster by taking flight — either by moving abroad, or for those without means, by moving away from the capital city.

However, the more people leave, the less chance remains to avert a disaster.

It is possible to reverse the negative trend. Russians need to understand their history and know themselves. They — we — sit in our Moscow apartments and plan our escape because we fear the people on the street below. We are alienated from each other. It is as if the Middle Ages never ended.

Our experience shows that our fears are not unfounded. But it also shows that those fears might be exaggerated.

The only way to find out how things really stand is to get to know and build bridges between each other. That is much simpler than rethinking national history. What's more, it does not require any special effort.

When a person gets cold, he can warm himself by focusing his thoughts away from the cold and taking long, deep breaths. In the same way, Russians need to shift their thoughts away from some impending disaster and take a longer-term approach to life than a focus on the opening and closing ruble exchange rate each day.

It helps to get into that broader rhythm now, at the start of the school year. I, for example, started school in 1983, in the post-Brezhnev period of the Soviet Union at the peak of the Cold War. I graduated in 1993, in what had become a completely different country and a radically changed world.

Hundreds of thousands of Russian children started school on Sept. 1. They will also graduate in what will be a completely different national and international environment. Even now, Russia is not the country we see portrayed on state-controlled television.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.